Newspaper articles from the First World War documented many gifts from the public to war hospitals in Newcastle. These included: a muffler, games, two pairs of socks, one pair of bedsocks, magazines and stationery from Mrs Lumley of Sixth Avenue on behalf of the British Women’s Temperance Association to the Northumberland War Hospital; lettuces from Mrs Wood of Seventh Avenue to the No 1 Northern General Hospital; a contribution from Mrs Whitfield of Ninth Avenue to purchase a bell tent for the Northumberland War Hospital and a gift of cigarettes by William Castle of Tenth Avenue to ‘Armstrong College Hospital’, all of which came to light during research for our ‘Heaton Avenues in Wartime’ project.

In total, Newcastle had over 3000 military hospital beds as well as a Voluntary Aid Detachment Hospital in Pendower Hall, run by the Red Cross and a St John’s Ambulance Hospital in Jesmond, both of which would have been used for convalescence. Patients would arrive by train and were cared for by huge numbers of doctors, nurses and orderlies, often drawn from providing care to the rest of the population or given only basic training as volunteers.

No 1 Northern General Hospital

Work on the building of Armstrong College, now the original buildings of Newcastle University, had started in 1888, with the third and final stage being completed in 1914. However, before the college could occupy the building, it was requisitioned by the government along with the rest of the college buildings for use as the 1st Northern General Hospital on the outbreak of World War I. The No 1 Northern General Hospital had capacity for 104 officers and 1420 other ranks. The hospital worked very closely with the Royal Victoria Infirmary, which had only recently opened (the last patients having moved from the old infirmary on Forth Banks in 1908).

The arrangement included provision of an additional 112 beds for military use at the RVI, created in the spaces between the ward blocks, as well as the RVI providing specialist functions such as x-ray, an arrangement that was not without its problems. On 9 October, Lieutenant Colonel Gowans, Officer in Command of No 1 Northern General wrote to the matron of the RVI, informing her that the army would, due to the pressure of war demands, be removing Territorial Army Nurses from staffing these beds at the RVI.

A special meeting was called on 15 October, to which Colonel Gowans was invited, which evidently became quite heated. The argument was around who should bear the cost of nursing patients in the military requisitioned beds as well as how and at what cost, additional accommodation could be provided for the extra nurses. The house governor estimated that the additional cost to the RVI would not be less than £1,000 per year and senior staff of the Infirmary were of the view that this should be borne by the Government. An additional cost of 6d per head per day was suggested, on top of the 3/- per day already paid. Colonel Gowan questioned whether there was indeed any additional cost to be borne by the Infirmary, at which point the house governor replied:

“that it was a well known fact, easily verified by any of the reports of the large hospitals, that a hospital bed cost about £100 per year to maintain; as 3/- per day came to £54 per year, there was a balance on the wrong side of between £40 and £50. Moreover, about half of the operations performed on territorial patients had been done in this Infirmary and at the cost of this Infirmary, and in the theatres nursed by civil nurses; that the electrical treatment for the Armstrong College had been done in this Infirmary by our nurses; that the X-ray work for the College had been done here and that we had borne the cost of all plates, materials etc, with only one orderly to assist in the department; that all the bacteriological and pathological work had been done here; that Mr Wardale uses the large operating theatre in ward 3 for military cases from the college; that many thousands of the troops had been inoculated in the Infirmary; that the mortuary and post mortem rooms were used by the College; and that by making use of these departments, they have saved themselves the expense and trouble of providing and running these departments themselves. It was stated again that the Committee desired to make no profit out of this matter, but they thought it desirable that the help which they had already given should be recognised rather more in the future than it had been in the past.”

Colonel Gowan’s response is not recorded!

This incident aside, it is evident that the RVI and the military hospital worked closely together throughout the war. Many of the RVI’s medical staff received honorary commissions and spent periods of up to a year caring for troops either at the front or in UK military hospitals. So much so, that the RVI’s 1916 annual report for the surgical department records that four of the eight honorary surgical staff and two of the four surgical registrars were away throughout the year on military service ‘throwing much extra work on those who were left’, so much so, that statistics on the surgery carried out were not available, but the report does acknowledge that work done by senior students to fill in for house officers.

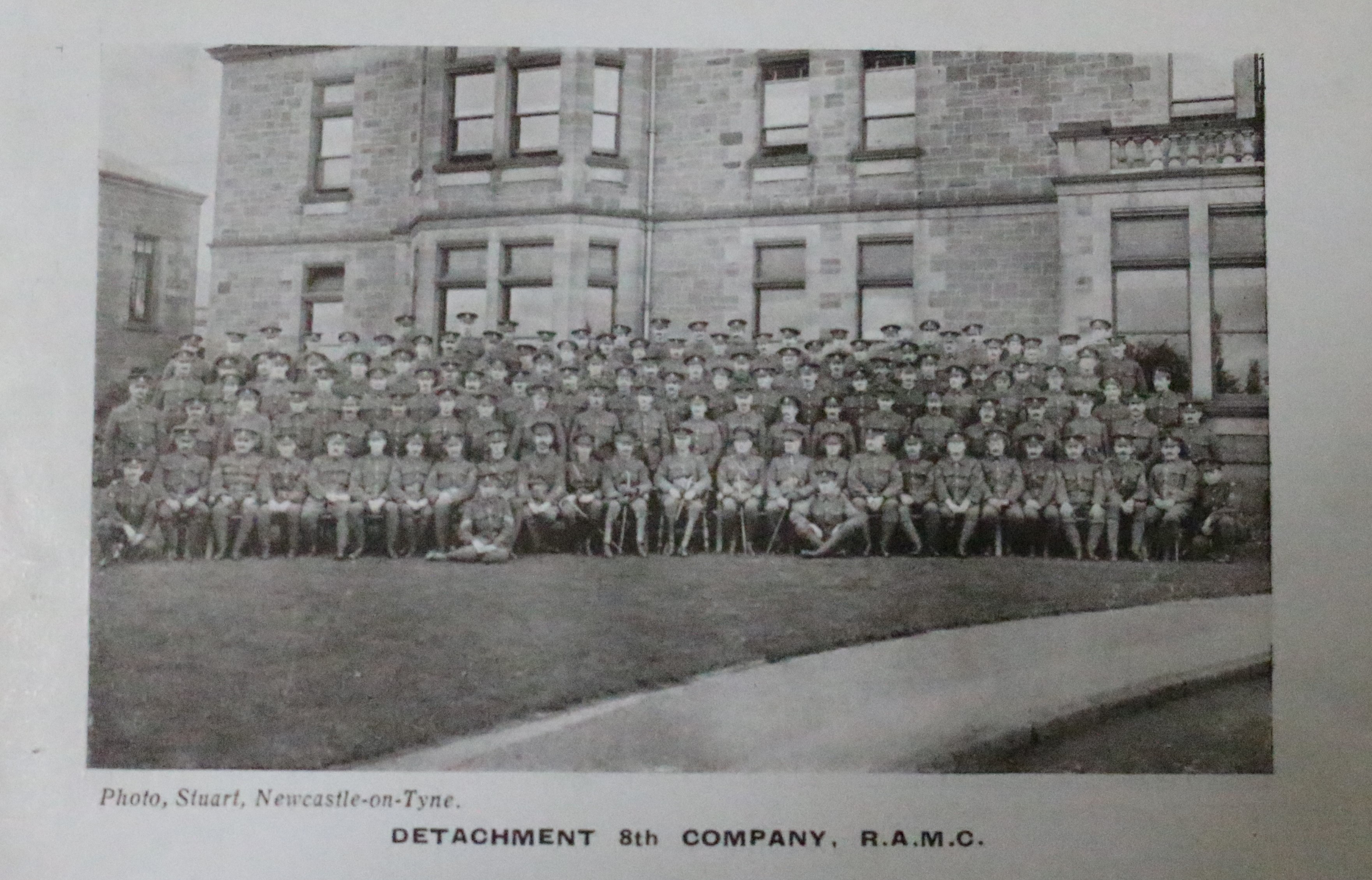

The RVI also provided training for Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) Nurses, who received a month of basic training before being used to supplement the qualified staff, both at home and at the front. The VAD nurses can clearly be seen in the staff photo of the 1st Northern General as they wear a Red Cross on their apron.

The RVI and the military hospital also worked closely on the creation of a military orthopaedic Hospital, following a model already established in Leeds. The intention was to provide specialist rehabilitation facilities for soldiers who had lost or damaged limbs. An initial meeting was held on 25 September 1917 to discuss plans for a facility with up to 1500 beds, to be built on the RVI site. On 15 October, a meeting of the Committee and local dignitaries welcomed the former King Manuel II of Portugal, who had been deposed in 1910 and made himself available to the allies in support of the war. He was assigned to a post in the British Red Cross, much to his disappointment, but played a very active role in supporting the organisation during the war. The Red Cross promised to provide funding of £2,500 for equipment and a further £10,000 was promised from the War Office, but only when a total of £45,000 had been gathered from local fund raising efforts. It was September 1918 before the funds were raised and when, on 3 December, the Committee received a letter from Major General Bedford asking that completion of the centre should be expedited so that patients could be moved from the Northern General, so that the College could be evacuated, building still hadn’t started. By June 1919, the work was finally underway having been slowed down by the lack of builders and materials, although arguments were still going on in 1924 about the ownership of equipment and facilities. The three wards eventually built (pavilions 1,2 and 3), along with other support and facilities remained in use until the 1970s.

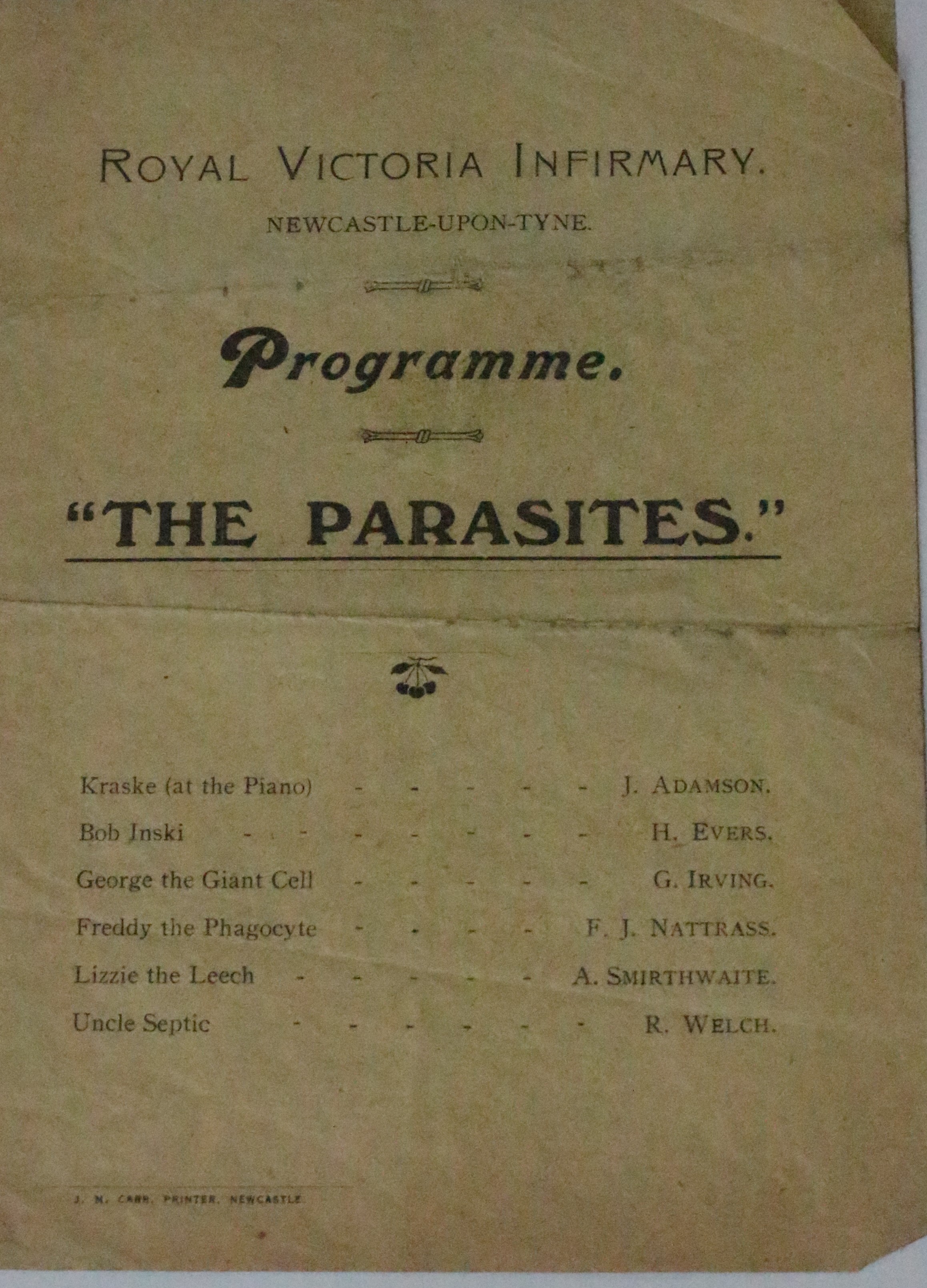

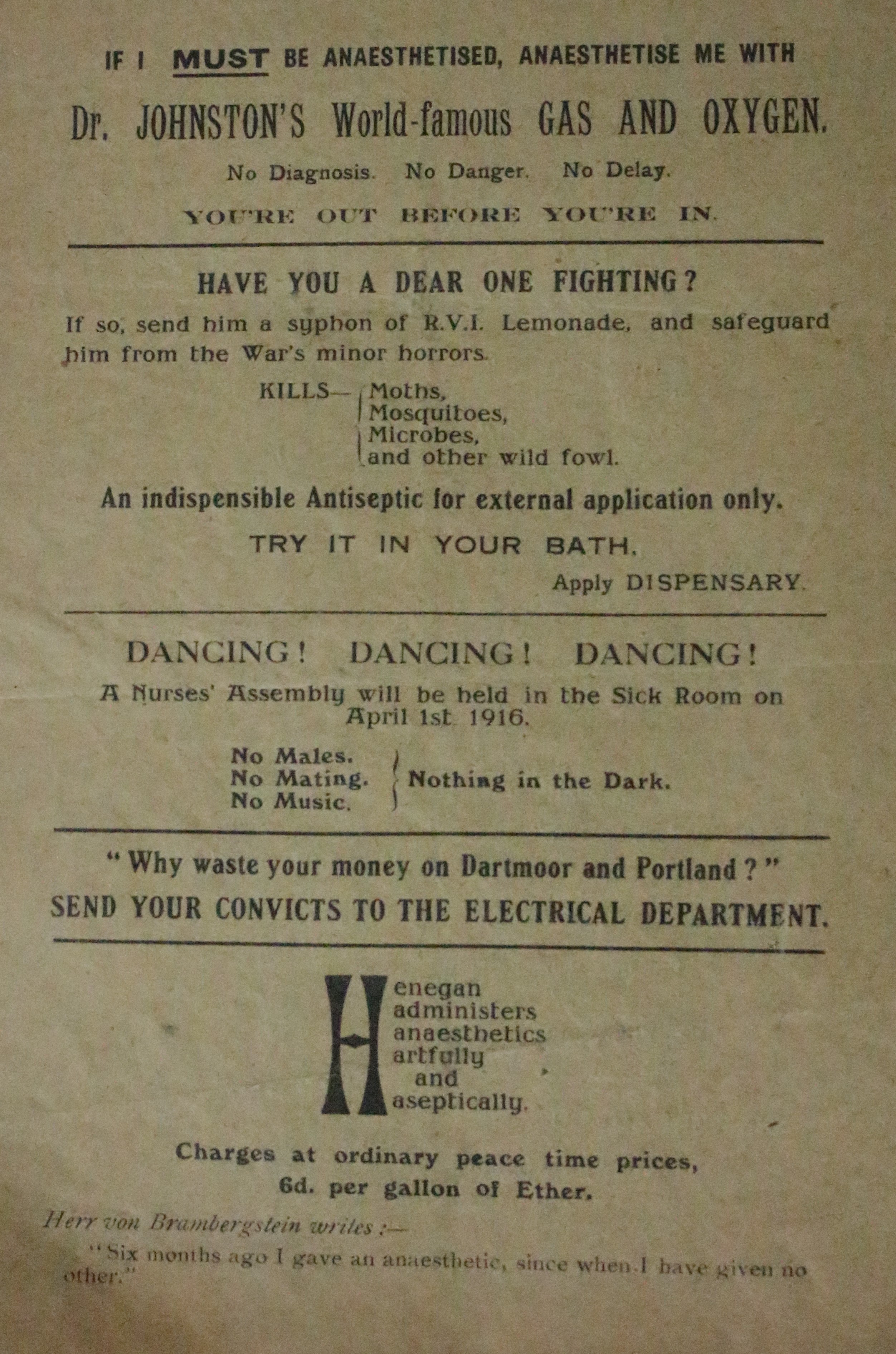

Despite the many hardships and difficulties the war posed for soldiers and staff, there was also evidence of the comradeship and sense of humour of those working together in the hospitals, as can be seen by this playbill for entertainment put on during the war. The spoof adverts in particular provide a window on the circumstances they were living through.

Northumberland War Hospital

On 24 February 1915, Alderman William H Stephenson informed the city council that arrangements had been made with the government authorities for the utilisation of The City Asylum as a hospital for the forces, and for the patients being temporarily accommodated in other asylums.

The City Asylum, which we now know as St Nicholas’ Hospital in Gosforth, had opened in 1869, having been built on a 50 acre farmstead, known as Dodd’s Farm. It was built in response to chronic overcrowding in local hospitals for the mentally ill and reflected the latest medical thinking concerning care of the mentally ill. It had capacity for over 400 patients and included its own farm among other amenities.

Plans moved quickly, reflecting the urgent need for hospital provision for injured troops brought home from the front and, on 19 May 1915, Alderman Stephenson, chairman of the Lunatic Asylum Visiting Committee presented a report to the council setting out the arrangements for the operation of the Northumberland War Hospital.

In order to clear the asylum of patients, arrangements were made to transfer them to the care of other nearby local authorities. The report noted that the Board of Control had permitted a certain percentage of overcrowding in the receiving asylums. One can only imagine the impact of these arrangements on the mentally ill patients, uprooted and moved around the region. However, it freed up a substantial and modern hospital site to meet the urgent need to care for injured troops returning from the war.

Alderman Stephenson’s report goes on to set out the arrangements for the operation of the hospital for the duration of the war. The Visiting Committee were to retain the lay administration of the hospital, with the payment by the Army Council of:

• Charges in connection with the buildings and equipment; and

• Charges in connection with the maintenance of staff and soldier patients.

The hospital was handed over as a going concern with the whole of the staff, medical, engineering, stores, farm etc and the nursing and attendant staff. The War Office was to assume sole responsibility for the medical care and treatment of the soldiers and the management of the hospital. Lieutenant Colonel Prescott DSO RAMC was appointed Administrator and the Acting Medical Officer of the Asylum, Dr McPhail was appointed Registrar, with the rank of Major. The nursing staff was augmented and the whole of the male attendants at the asylum transferred to the Royal Army Medical Corps for the duration. The nursing staff were to be accommodated in a newly built nurses home and additional villa blocks, which were still under construction. The medical staff were to be accommodated in tents in the grounds. The Northumberland War Hospital, when it opened in the summer of 1915 had accommodation for 1040 patients, two and a half times the number previously accommodated on the site, which gives some indication of both the degree of overcrowding and the urgent need for hospital provision.

Brighton Grove Hospital

In addition, in Newcastle alone there was specialist venereal disease provision for 48 officers and 552 other ranks at Brighton Grove Hospital (on the site of the old Newcastle General). Sexually transmitted disease (Venereal Disease or VD) was a huge issue in the forces before the days of effective barrier contraception or treatments. When British soldiers set off for the trenches in 1914, folded inside each of their Pay Books was a short message. It contained a piece of homely advice, attributed to the Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, which included:

You are sure to meet a welcome and to be trusted; your conduct must justify that welcome and that trust.

Your duty cannot be done unless your health is sound, so keep constantly on your guard against any excesses.

In this new experience you may find temptations both in wine and women.

You must entirely resist both temptations, and, while treating all women with perfect courtesy, you should avoid any intimacy.

In his memoirs Private Frank Richards, who served continuously on the Western Front, recorded men’s responses to these words: “They may as well have not been issued for all the notice we took of them.”

Licensed brothels had existed in France since the mid-19th Century – the war saw the trade flourish. Brothels displayed blue lamps if they were for officers and red lamps for other ranks. Outside red lamp establishments, queues or crowds of men were often seen.

Cpl Jack Wood compared the scene he witnessed to “a crowd, waiting for a cup tie at a football final in Blighty“. Others saw brothel visits as a physical necessity – it was an era when sexual abstinence for men was considered harmful to their health. Physical need made it more acceptable for married men, rather than single men, to visit prostitutes. Twenty-four hours before the major British offensive of the Battle of Loos, Pte Richards saw “three hundred men in a queue, all waiting their turns to go in the Red Lamp”.

Brothel visits could also be a way to avoid death. They gave soldiers a chance to swap time in the trenches for a few weeks in a hospital bed. According to Gunner Rowland Myrddyn Luther, who enlisted in September 1914, and served through to the Allied advance of 1918, a great many soldiers were prepared to chance venereal disease, rather than face a return to the front.

The numbers infected were “stupendous“. Around 400,000 cases of venereal disease were treated during the course of the war. In 1916, one in five of all admissions of British and dominion troops to hospitals in France and Belgium were for VD.

Walkergate Hospital

Council Minutes record that Mr Stableforth had been approached by the military authorities requesting that the Sanitary Committee could handle their cases of infectious diseases at Walkergate Hospital (Walkergate had been built in 1888 as an infectious diseases hospital). It was reported that there was insufficient accommodation, but that it had been agreed that two additional pavilions could be constructed to accommodate the military patients. The design of Walkergate, and presumably the temporary ‘pavilions’ was to provide a single story ward with a long covered verandah, where patients could be wheeled outside for fresh air, which was considered vital to their recovery, particularly with conditions such as TB. A subsequent minute records contracts with:

• Stanley Miller to build the new pavilions at a cost of £2,126/8/-;

• Walter Dix and Co to provide heating and hot water at a cost of £261/2/8; and

• William T. Wallace for making roads into the new pavilions.

The pavilions were built on the east side of Benfield Road, opposite the main hospital and were intended to be removed after the war. In practice, they remained in use, though not as part of the hospital until 1979.

Heaton Avenues in Wartime

This article was researched and written by Heaton History Group member, Michael Proctor, as part of our HLF funded project, ‘Heaton Avenues in Wartime’. A display about the civilian war effort of the people of the avenues will open at the Chillingham pub in early May 2015 and will be in place for approximately two months.

Thank you to Tyne and Wear Archives for permission to use the photographs in this article.

If you can provide any further information about Heaton connections to the hospitals, please either leave a message by clicking on the link immediately below the article title or email chris.jackson@heatonhistorygroup.org

No. 1 Northern General Hospital 1916. Are there any records showing the names of the nurses shown in this photograph and the photograph of The Northumberland War Hospital? I believe that my grandmother worked at the RVI during the First World War. This is a most interesting and informative article. Thank you.

Unfortunately we don’t have the names of the people on the No 1 Northern General Hospital photo. The pictures from the Northumberland War Hospital were part of a set of 4 in a Xmas card produced for patients. The Tyne and Wear archives have extensive records from the RVI, but I can’t recall whether that included staff lists.

Is a sharper image available of the photo of the RAMC at Northumberland War Hospital. I have just discovered a photo of my Grandfather in RAMC uniform and he was an Attendant at St Nicholas Hospital, he may be on this photograph. Thanks for any help you can give.

Hi Lynne,

The orginal is in Tyne and Wear archives so a visit there would be your best chance. Good luck.

Chris (secretary)

I’m looking for a hospital that was called Seaton hospital around 1915-1918

Thank you for this information. I am looking for some information on my grandfather, Fred Cutts. He was from Brinkworth, Wiltshire. My mother told us that he was one of the few in his platoon to survive a gas attack. He spent a long time in the Newcastle Hospital. I can’t find his records. Can any one give me an idea of how to trace Medical records during WWI? Thank you

My grandfather was sent to the No. 1 Northern General Hospital on 7 January 1916. Oddly his records also show a concurrent admission to the “Workhouse Military” hospital, also in Newcastle-on-tyne. Are the two one-and-the-same? I can’t find any reference to the “Workhouse Military” hospital.

Hello Gary,

Unfortunately Tyne and Wear Archives and Newcastle local history library are currently closed due to the pandemic but when they are open, they offer a research service by mail.

In the meantime, two of our researchers have a little information. Michael Proctor says ‘ I believe the Workhouse Military Hospital was what became Newcastle General Hospital. I came across some references to it in the research I did for the article. I believe it specialised in treating sexually transmitted infections, which were rife amongst soldiers during WW1 and may explain two different admissions at broadly the same time.‘

Arthur Andrews has found this link

https://wartimememoriesproject.com/greatwar/hospitals/hospital.php?pid=790

I hope they help.

Chris (Secretary, Heaton History Group)