It is late evening on a Saturday in early August 1926. The sun set an hour ago, but the sky in the west is still bright. The gaslamps of Heaton railway station dimly illuminate the expanse of the glass canopy above. The two platforms of the station are virtually deserted, and its signal box is closed for the night. The station foreman is in his small wooden office, catching up with the paperwork now that the trains are less frequent. The last of the birds are singing their songs in the trees above the cutting walls before they settle down for the night.

From the east comes a distant whistle, high pitched and short, and then the puffing and wheezing of a steam locomotive. Round the bend from Heaton Yard appears an engine, small and black but kept clean and shiny by its crew, starting up its short train. It is a ‘Special Goods’ for Blaydon made up of 13 wagons from railway companies far and wide. Slowly the engine clanks by, its crew exchanging a wave with the station foreman whose head pokes out from his office door to watch its passing.

A procession of wooden goods wagons goes rumbling and squealing through the platforms, the noise echoing off the walls that surround Heaton station in its cutting. The first wagon has ‘GW’ painted on its side, an indication that it belongs to the mighty Great Western Railway. Then comes one with ‘L&Y’ indicating that until the 1923 ‘Grouping’ of the railway companies it had belonged to the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. The next wagon is brand new grain wagon, probably filled with the products of a farm somewhere in Northumberland. It has the letters LNER on the side, a company formed only three years ago, and one which took over the running of Heaton station and its trains from the old North Eastern Railway.

The train clanks its way along the up main line; the driver has no worries about holding up fast express trains at this time of night and has a clear run at least as far as Manors. That’s the next station towards Newcastle to the west, after the cutting in which Heaton station stands opens out for the junction at Riverside, and then the great viaduct over the Ouseburn. The red glow from the tail lamp on the guards van slowly disappears off down the line as the steam, trapped under the huge glass canopy above, slowly starts to drift away through the trees and into the darkening sky.

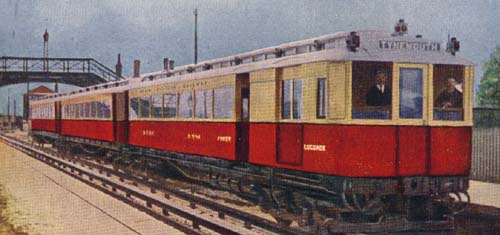

Ten minutes later a different sound drifts in from the east. This time it’s the swishing and clackety-clack of a much faster train running in on the line from Tynemouth and the coast. It’s one of the old North Eastern Railway’s electric trains, built in 1904 but still performing a sterling service over 20 years later. It’s possible to tell from the roofs that the second two carriages in the train are much newer, built only six years ago to replace the trains lost in the fire at Heaton Car Sheds. Some of the cars are still painted in the old North Eastern Railway crimson lake, but others have already acquired the new drab teak colour favoured by the LNER. The lights from the carriages illuminate the cutting walls as the train speeds into the station, displaying ‘CENTRAL’ on the front.

Experienced driver

At first it appears it’s not going to stop in time, but the driver, William Skinner of Felton Street, Byker, applies the brakes firmly and the train squeals to a halt in the platform. The sliding door of the van section of the first carriage rumbles open and out steps Skinner onto the platform, standing about two feet from his train. The train is made of wood, with matchboard on the lower half, and large windows above. Inside it looks comfortable but functional, and only one young couple can be seen inside the first class compartment of the first vehicle. There is a large parcels compartment in this first coach, one of the motor luggage composite carriages built at the opening of electric services, to carry fish from the coast and the prams of toddlers on their way to the beach.

Skinner is 35 years old and has worked on the railway for 18 years, starting off as a cleaner and being promoted to a driver six years ago. He has been mainly been driving goods trains of late, but passed for driving these electric trains four years ago. This is a nice change for him, running out to the coast on a clean electric service instead of the heat, smoke, and grime of a goods train. He has enjoyed his ride so far, fast out to Monkseaton and then stopping at all stations on the return to Newcastle Central station. After this stop he only has Manors to go before his arrival back at the Central. His wife and five children will be waiting for him at his home, which is only a mile away from where his train currently waits.

Last trip

The station foreman emerges from the gloom and stands on the platform to watch the passengers disembark. They’re mainly day-trippers who’ve enjoyed an evening at the coast, with few people getting on at this time of night. He notices Skinner on the platform, which seems a bit odd to him, and shouts hello. “Is this your last trip?” he asks, to which Skinner replies “Yes!” The train’s guard, George Patterson, closes the metal gates on the old carriages, and the doors on the new ones, and gives a blast on his whistle. Skinner gets back into his van and re-enters his cab, but doesn’t take the time to slide the door closed. The train’s Westinghouse brakes hiss as they’re released and with a whirr and a whine the train accelerates quickly off towards Newcastle, blue flashes of electricity lighting up the station as the current arcs from the conductor rail beside the tracks.

The train now gathers speed, getting up to its full pace as it rattles over the pointwork at Riverside Junction, where the line to the shipyards of Walker and Wallsend peels off to the left. Over the huge iron structure of the Ouseburn viaduct it roars, the lights of the factories and warehouses dimly twinkling in the gloom below. In his van at the rear of the train, Patterson is engaged in making notes for his next trip as the train clickety-clicks its way through the darkness towards Newcastle. Into the cutting it goes, towards Manors station and its complex junction of lines. It rattles past Argyle Street signal box, its signalman hard at work in his little illuminated world, and into the bend at Manors. But as Patterson looks up from his work and out of the window his heart skips a beat; he sees that they’re already pulling into the platforms but still going full speed. He hadn’t noticed, so engaged was he in his work, that Skinner hadn’t tested the brakes at Argyle Street as he should have done. Up he jumps, and makes for the door to the driver’s compartment at the back of the train to apply the Westinghouse brake.

The signalman at Manors, Francis Topping, had it all planned out. The goods train that had passed Heaton fifteen minutes ago had arrived at his signal box ten minutes later. It had stood at his Up Home Main Line signal for a minute or two whilst he let traffic clear the junction but when he was ready for her to move he’d set the signal for the train and with a toot and a hiss it was already underway. His intention was to let it clear the junction whilst, as the rules stated, he brought the passenger train almost to a stop on approach to the platforms before allowing it to pull in. As soon as he’d heard the bell in his box that signalled the entrance of the passenger into his section he’d set the ‘calling-on’ signal to allow it into the station.

But now Topping turns to look out of his window and up the line towards Heaton and his face freezes in terror. He immediately realises that the train is going far too fast to stop at the signal as he’d intended. He watches it race at full speed towards his signal box, which straddles the tracks to the west of the station and affords a grandstand view of the drama playing out below. The passenger train heads inexorably towards the special goods that is now across the junction in front of it and leaving nowhere to go. In the cabin at the back of the train George Patterson is frantically applying the Westinghouse brake to slow the train down, but it’s too late. It ploughs into the third vehicle of the goods train, a loaded grain wagon, with a glancing blow. Splinters of wood and metal fly into the air. The electric train lurches to the left, rips the steps from Topping’s signal cabin, and jams itself against the parapet wall of the railway viaduct, balancing above the street some 60 feet below, bricks and rubble falling down onto the road. The other vehicles are derailed too but stay upright, crashing into the back of the first, and a cloud of dust and smoke fills the air.

Signalman Topping regains his senses, and springs into action. He knows his duty in an emergency like this, and immediately protects all of the lines leading to and from his signalbox and summons ambulances and the police. Thankfully the automatic circuit-breaker for the electrical system has worked as intended and there is no fire amongst the wooden coaches and wagons. He watches as passengers warily make their way out of the carriages, and the driver and fireman of the goods train run back to help them. He looks down on the wreckage below and knows this is going to take some time to sort out. “Just what was that driver doing?” he wonders to himself, almost in disbelief.

Within minutes Inspector Gill from the Northumberland Constabulary is running up the ramp onto the platform at Manors station from the street below with a number of his constables. He clambers down onto the tracks and makes his way towards the half-demolished first carriage of the passenger train. Carefully picking his way through shattered wood planks and broken glass, he reaches what is left of the driver’s cabin. With the help of his men, he begins to clear the wreckage in expectation of finding the driver’s body. He moves aside twisted metal and wood, grains of wheat falling down onto the tracks below from the destroyed wagon which had borne the brunt of the impact. But search as they might, they find no sign of Skinner’s body.

Dead man’s handle

Eventually the inspector reaches the control unit of the electric train. He finds the controller, which limits the power to the train and thus its speed. The handle is in the ‘Full Power’ position, with the reversing key in ‘Forward’. Skinner hadn’t even made any attempt to stop accelerating the train. The controller has an important safety feature, the ‘Dead Man’s Handle’. This is actually a button on the top of the controller which must be pressed down at all times by the driver or the power to the train is automatically cut-out. The dead man’s control on Skinner’s train could never do its job, however, because he’d seen to it himself that it would not work.

Inspector Gill finds the button on the controller cleverly tied down by two handkerchiefs, which together exert enough pressure on the button to ensure it is kept constantly pressed. A red handkerchief is looped around the controller handle and over the control button and knotted in place with a triple-knot. Over this the second hanky, a white one, is tied even tighter around the first adding to the pressure on the button. This is secured with a double knot. The arrangement of the hankies evidently saved Skinner from having to constantly press the dead man’s control, something which became wearisome after a while, and leave the controller with the train still under power.

Inspector Murray arrives at around 12:50am and examines the handkerchiefs. He finds no identifying marks on either, and removes them for safe keeping. For the next two hours a search of the wreckage continues. Thankfully there were only two passengers travelling in the first vehicle of the train, a young couple from Durham, who miraculously only suffered leg injuries and shock. The other 150 or so passengers in the remaining five coaches of the train walked away relatively unscathed. What the constables and inspectors are searching for is Skinner, and he is nowhere to be seen. Some firemen are asked to search the roofs of the houses in the street below in case his body had been catapulted from the train, but to no avail. Eventually Murray calls over Sergeant Sandels and tells him to start walking back up the line towards Heaton to see if he can see any sign of Skinner, or anything untoward.

So Sandels sets off walking, back past the silent and dark carriages of the now-empty 9:47pm Newcastle to Newcastle (via Monkseaton), down the ramp at the end of Manors station platform, and into the cutting towards Argyle Street signal box. The crunch of the ballast is loud beneath his feet as he walks up through the damp cutting, scanning the darkness below with his eyes for the sight of anything strange. He passes the entrance to the Quayside railway, its foreboding tunnel disappearing to his right and down to the river where ships unload their wares into waiting railway wagons. He passes under the short tunnel where New Bridge Street passes overhead, and then under Ingham Place and Stoddart Street. The lights of the signals are all on red as far as he can see along the straight line ahead, their beams glinting off the shiny railtops of the many sidings and running lines. Out across the Ouseburn Viaduct he strides, with the smells of industry and animals drifting up from below, the sky lightening to the east ahead of him. He hears a ship’s hooter echo mournfully from the River Tyne to his right as he presses on past Riverside Junction signal box and the little station at Byker.

Eventually, after walking over a mile, he comes to the bridge carrying Heaton Park Road over the railway. There he sees something on the tracks; a dark shape lying beside the electrified rail on the left-hand side of the lines as he faces east. Sandels runs towards this object and bends down to look more closely; it is Skinner, lying on his back with his feet facing away towards Heaton station, his right arm outstretched below the conductor rail and his eyes staring lifelessly up. Sandels checks for a pulse, not expecting to find one. He doesn’t. Skinner is dead and already quite cold.

Sandels runs to Heaton station and asks them to call for a local doctor. Dr Blench arrives after half an hour, during which Sandels has been standing guard over Skinner, trying to comprehend what has happened that night. The doctor examines the body, and finds that the back of his head is badly injured and his skull fractured. There are also bruises down his neck and back. The two men then get up and walk over to the row of iron columns supporting the road above. On the nearest column to the body they find a patch of blood. Then on the next another patch, higher than the first, and the same on the third column higher still. On the first of the bridge’s columns that Skinner’s train would have reached they find a patch of blood, quite high up, but about the height at which Skinner’s head would have been whilst leaning from the train. Sandels sits down on the rail with a sigh and waits for his inspector to arrive. “The damn fool!” he whispers to himself.

Epilogue

Nobody will ever know what went through Skinner’s mind that night. It was clear that tying down the ‘dead man’s control’ was a common practice for him. But why did he set his train in motion then go to the door of his van to look back along the train? Why did he forget about the bridge, under which he’d passed many times before? That accident at Manors thankfully claimed no further lives, and Skinner was the only victim of his own misfortune. His widow and five children were left to ponder his actions, and given his implication in the accident it is unlikely that the railway company were particularly generous towards them. Whilst there was quite a stir in the area at the time of the accident, it was soon forgotten and the electric trains went back to running their busy service for the next 35 years.

Postscript

Since this article was written, the author and Chris Jackson, Secretary of Heaton History Group, were privileged to meet Olive Renwick, daughter of Francis Topping, the signalman on duty at Manors on the night of the accident. See the article ‘The Signalman and his Daughter’ for more about them both.

Author

Researched and written by Alistair Ford. Alistair has lived in Heaton for 10 years. He is a researcher into sustainable transport and climate change at Newcastle University with a ‘passing interest in railways’.

Sources

Newspaper report of the incident: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2507&dat=19260809&id=Y51AAAAAIBAJ&sjid=SKUMAAAAIBAJ&pg=2327,4806101&hl=en

Newspaper report of the inquiry: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2507&dat=19260819&id=bJ1AAAAAIBAJ&sjid=SKUMAAAAIBAJ&pg=6455,6064739&hl=en

Accident report: http://www.railwaysarchive.co.uk/documents/MoT_ManorsJunction1926.pdf

Can you help?

If you have further information about this incident or any of the people mentioned or have knowledge, memories or photographs of railways in Heaton more generally that you’d like to share, please either leave a comment on this website by clicking on the link immediately below this article title or email Chris Jackson, Secretary, Heaton History Group (chris.jackson@heatonhistorygroup.org).

Wonderful: gripping and intensely atmospheric. Thank-you.

This story made me realise just how little we know of the affairs of Heaton Junction Marshalling Yard. It was an enormous site that did a host of work with trains, but the most fascinating procedure was the marshalling of freight. Alistair mentions the Special Goods made up of 13 carriages of varying contents from all over the kingdom – and possibly the world. All those carriages came to Heaton as consolidated freight from various places; they were then separated and collected (marshalled) into exactly the sort of package that was on its way to Blaydon where the goods would be unloaded and distributed about the area there. I don’t remember (it was decades ago when I last read it) if Jack Common spoke of the work done by the Marshalling Yard, but it was an enormous endeavour that went on 24hrs a day (as a child I could hear it late at night through my open bedroom window way up near the park) yet I actually knew nothing of the affair – as, I suspect, did most other folk. It would be thrilling to discover that the archives of the administration still existed. I don’t hold out much hope, as so much of the properties belonging to the railways seems to have disappeared; for example: some years ago I spent a great deal of time looking for BR tableware in the hope of finding one of their engraved glasses; I found nothing! I keep a permanent eye open to this day.

We’ve a talk on Heaton’s railway history coming up early next year by curator of the National Railway Museum, which should be interesting.

Also one of our members told me he plans to research a book on it. But he has to remain nameless as he said not to tell his wife!

Hi Keith,

Thanks for your comments. The role of the railway in Heaton is certainly a pivotal one, and I look forward very much to the talk in the new year. I must admit to not knowing a great deal about the operation of the marshalling yards at Heaton. It seems that, despite the construction of the massive New Bridge Street goods depot in the early part of the century, the various goods yards around Tyneside continued to play quite a role until the 1960s. Heaton obviously had a lot of traffic servicing the railway side of things (coal for locomotives, materials for carriage repairs), plus the big domestic goods yards adjacent to Chillingham Road/Rothbury Terrace.

These photos of C.A. Parsons works in the 1930s show some glimpses of the scene:

http://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/image/epw042109 – this includes one of the electric units featured in the tale of William Skinner, but look at the array of sidings (you have to register and log-in to be able to zoom the view). There seems to be quite an incredible array of railway wagons in Parsons works themselves, and the factory in the foreground (was that the Metal Box Company?). There also appear to be hundreds of wagons over beside the carriage sidings!

http://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/image/epw042111 – this picture shows a bit more of the sidings to the west of the locomotive coaling stage. The number of engines on the shed suggests that this might be a Sunday, so perhaps during the week even more goods traffic might be visible!

http://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/image/eaw005492 – this image, taken after the war, shows the view back towards the avenues where Jack Common grew up. You can see the extensive sidings backing onto Hartford Street and the NER terraces to the east of Chillingham Road (and also Iris Brickworks in that picture too!).

http://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/image/eaw005494 – this gives a birds-eye view of the same scene, looking down on the goods sidings. You can see wagons loaded with barrels, timber, and steelwork. There’s also the household coal depot to the left, with a few wagons already unloaded. You can see a very long goods train pulling out of the sidings next to the locomotive depot.

http://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/image/eaw022480 – you can see a better view of the unloading facilities in this view, with some covered goods vans parked up at the shed at the back of Spencer Street.

As for what the ‘special goods’ was conveying: who knows?! The loaded grain wagon is particularly intriguing; it could have been heading up towards Consett, or along the Tyne Valley to Hexham perhaps? I’m not sure how much onward forwarding was done from Blaydon, so it’s anyone’s guess.

A good place to start researching might be the ‘Working Timetables’ that railway companies used to issue for each area. That might give an idea of what local goods workings used to go out from Heaton (including any private company sidings they might have shunted). These are probably held at the National Railway Museum so we might get an insight at the talk that’s coming up!

Hi Chris ,

Hope you’re well and busy.

The Frances (Frank) Topping , Signal Master mentioned in this fascinating posting was the father of a family friend, Mrs Olive Renwick, who was delighted to read the story of her father’s adventures which she can recall as a 9 year old child. She would be very pleased to discuss her memories of her father with yourself and/or Alistair Ford .

Brian Hedley

>

The 1926 collision at Manors is rather the tale of he Marie Celeste, where the main protagonist cannot explain the mystery! Nevertheless, it’s an interesting story.

A couple of factual errors in your account need attention. The first being the mention of gas lamps at Heaton Station. This station in common with most of the other stations in the North Tyneside electrified area was lit electrically. In the case of Heaton, this was done in 1904 as part of the Power & Lighting scheme between the North Eastern Railway (NER) and the Newcastle upon Tyne Electric Supply Company (BESCO). In the Heaton area, this scheme covered all of the railway yards, Walkergate Carriage Works, Heaton Car Sheds and the locomotive depot which were all electrically lit. This was independent from the traction scheme.

The second error was the mention of the train guard dealing with the metal gates. These were fitted to early batches of the rolling stock and were quickly dispensed with by 1905. these gates impeded passenger flows on the electric trains.

Finally, between 2010-14 I gave five talks on the Tyneside electrified lines to the Newcastle branch of the Stephenson Locomotive Society. These covered the main lines, the Riverside, Ponteland and Quayside Branches in considerable detail during the electrified era. This represented ten hours of speaking and the Heaton area played a major role in these talks.

Bill Donald

Dublin, Ireland.

Many thanks for those corrections, Bill. It would have been fascinating to have heard you talk about the local railway lines but it sounds as though you’re a bit far away now to speak at one of our monthly meetings. If you feel able to write anything about the history (or have anything written down already), we’d gladly publish an article on this website. Chris (Secretary, Heaton History Group).

David Stewart-David emailed:

The “Deadman’s handle” piece is very well written but has some inaccuracies e.g the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway simply painted a big L Y on their wagons (no ampersand). Similarly LNER wagons simply carried the letters NE – the LNER was a very hard up railway and NE saved paint on new wagons. During the Second World War the LNER also painted its locomotives with NE on the tenders. (Whether historical minutiae is simply nit-picking is a matter of judgement.)

Not sure if this thread is still open , thank you for this article very interesting. The train driver William Skinner was my grandfather, I have now acquired a full report of the accident for personnal reading. I had heard of the accident but no details, obviously not born then. Thank you for all the information given in this article.

Regards Ann Thompson (nee Skinner)