‘Her funeral was the most remarkable ever seen on —‘

‘[The] obsequies were celebrated with great splendour and solemnity. Several thousand Catholics were at her residence on the day of her death. A great banquet was provided by her son for all the neighbouring gentry and the poor received bountiful largesses of meat and money… ‘

‘Her body was transported on a barge surrounded by twenty other barges. The streets were lined with lit tapers.’

‘At – the magistrates and alderman with the whole glory of the town, attended at the landing place to wait on the coffin before the interment at -.’

Not Mary Tudor, England’s Catholic queen – her burial was a MUCH more subdued affair – but even if we tell you that the words represented by dashes are ‘Tyneside’, ‘Newcastle’ and ‘All Saints’, you might struggle to come up with an educated guess. This is the story of a woman often referred to (if she’s spoken of at all) as ‘Dorothy of Heaton’.

Catholic background

Dorothy Constable was born around 1580 probably at the home of her maternal grandfather at Wing in Buckinghamshire, (The estate is now a National Trust property) although her parents’ own home was Burton Constable in East Yorkshire, also now open to the public. The Constables were descended from a Norman knight who came to twelfth-century England and acquired an estate at Burton (later Burton Constable) by marriage. By the 16th century the estate comprised over 90,000 acres.

Dorothy’s father was Sir Henry Constable (1559-1608) who, despite a marriage into a strongly Catholic family, was appointed a Justice of the Peace then Sheriff before serving in Parliament twice for the borough of Hedon, which was surrounded by his estates, and then Knight of the Shire for Yorkshire in 1589. His subsequent career is said to have been hindered by his wife’s religious convictions.

Dorothy’s mother was born Margaret Dormer, daughter of William Dormer of Eythrope, Buckinghamshire and his second wife, Dorothy Catesby. Margaret was described as ‘a beauty in the external, full of majesty, tall in stature, sweet in countenance, fair in complexion’. This is a portrait of her.

The Dormer family were staunchly Catholic. Persecution of Catholics had begun in the reign of Henry VIII but it was under Elizabeth I that the Recusancy Acts of 1558 became law. The acts imposed various types of punishment, such as fines, property confiscation, and imprisonment on those who did not participate in Anglican religious activity, This was the world into which Dorothy was born in around 1580.

About 200 Catholics are thought to have been executed during Dorothy’s lifetime for refusal to comply with or openly opposing religious restrictions. They included 7th Earl of Northumberland, 1st Baron Percy, executed in 1572 after leading the 1569 Rising of the North, an unsuccessful attempt by Catholic nobles from Northern England to depose Queen Elizabeth I and replace her with Mary Queen of Scots. But many were executed simply for being ordained or harbouring Catholic priests, an example being Margaret Clitherow, crushed to death in her home town of York in 1586. Indeed, when Dorothy was just twelve years old, her own mother was imprisoned and spent several further spells in jail.

Heaton

On 10 March 1597, young Dorothy left Yorkshire to marry Roger Lawson, son of Sir Ralph Lawson of the Manor of Byker and Elizabeth Brough of Brough Hall, near Catterick. Roger’s mother had also been imprisoned for recusancy but then began to conform as did Roger. However, it appears that Dorothy soon had converted most of the Lawson family, apart from Roger, who remained Anglican until his deathbed.

It seems that Dorothy became increasingly aware of the threat her activities posed to her in-laws and so, while Roger practised the law mainly in London, Dorothy moved with their children away from Brough to Heaton Hall, another property of the Lawson family, described as ‘a convenient house and reasonably good seat’.

Here, Dorothy is said to have arranged for a priest to say mass once a month in the house. This necessitated carrying him in by night and ‘lodging him in a chamber’. She gradually employed Catholic servants and raised her children as Catholics. What we don’t know is whether the still standing King John’s Palace / Camera of Adam of Jesmond was used by Dorothy and her family at this time or was it already a ruin?

Despite seeming to have lived apart much of the time, the Lawsons had at least fourteen children (Her biographer says 14 but reports the family as giving the number as 19) including: Henry, Dorothy, Elizabeth, Edmund, Catherine, Mary, Ralph, George, Margaret, John, Roger, Thomas, James and Anne.

Dorothy junior, born in Yorkshire in 1600, joined an English Augustinian convent in Louvain as a choir nun. She died there aged only 26.

In 1624, Margaret, born in Heaton Hall in 1607, joined a Benedictine convent in Ghent which had been founded just a year earlier. She became an ‘infirmarian, dean and prioress’ before she died in 1672. The convent was politically active, supporting both Charles and James Stuart during their exile.

Mary, born in Heaton Hall in 1608, went to the same convent in Ghent, where she also died in 1672.

Ralph attended the English College, a seminary in Douai.

We don’t know much detail about the Lawsons’ life in Heaton, except that Roger was rarely here and there is a mention of a ‘visitation of sickness’, which seems to have taken place sometime between her husband Roger’s death in c 1614 and 1623. (There are independent references to outbreaks of coughs, colds and headaches in the north east between 1615 and 1617.)

St Anthony’s

In 1623, Dorothy moved her household to St Anthony’s near Walker. The name, still used today of course, derives from the area being dedicated to St Anthony ‘in Catholic times’. A picture of the saint was said to have been placed in a tree near the river for the comfort of seamen. St Anthony’s at this time was apparently an ‘ infinitely more pleasant spot’ than Heaton and had the advantage to her of being more remote but with easy access by boat. There was, however, no house there. Dorothy had to have one built.

In this appropriate spot, the Lawson house became a dedicated refuge for Jesuit priests. Dorothy was said to have spent a lot of time in prayer and also examined local children on their catechism. Not only did she invite her tenants and neighbours to mass and visit other Catholic recusants in jail, seemingly even taking in their washing (although she certainly had servants so maybe this didn’t involve actually getting her hands wet!), she is also said to have tended the sick and the poor, often on horseback. ‘Because she was a widow herself, she kept a purse of tuppences for widows’ and, as a result, was highly thought of in the area. Whether because of her popularity locally or the remoteness of her home, Dorothy was never prosecuted for her religious activities.

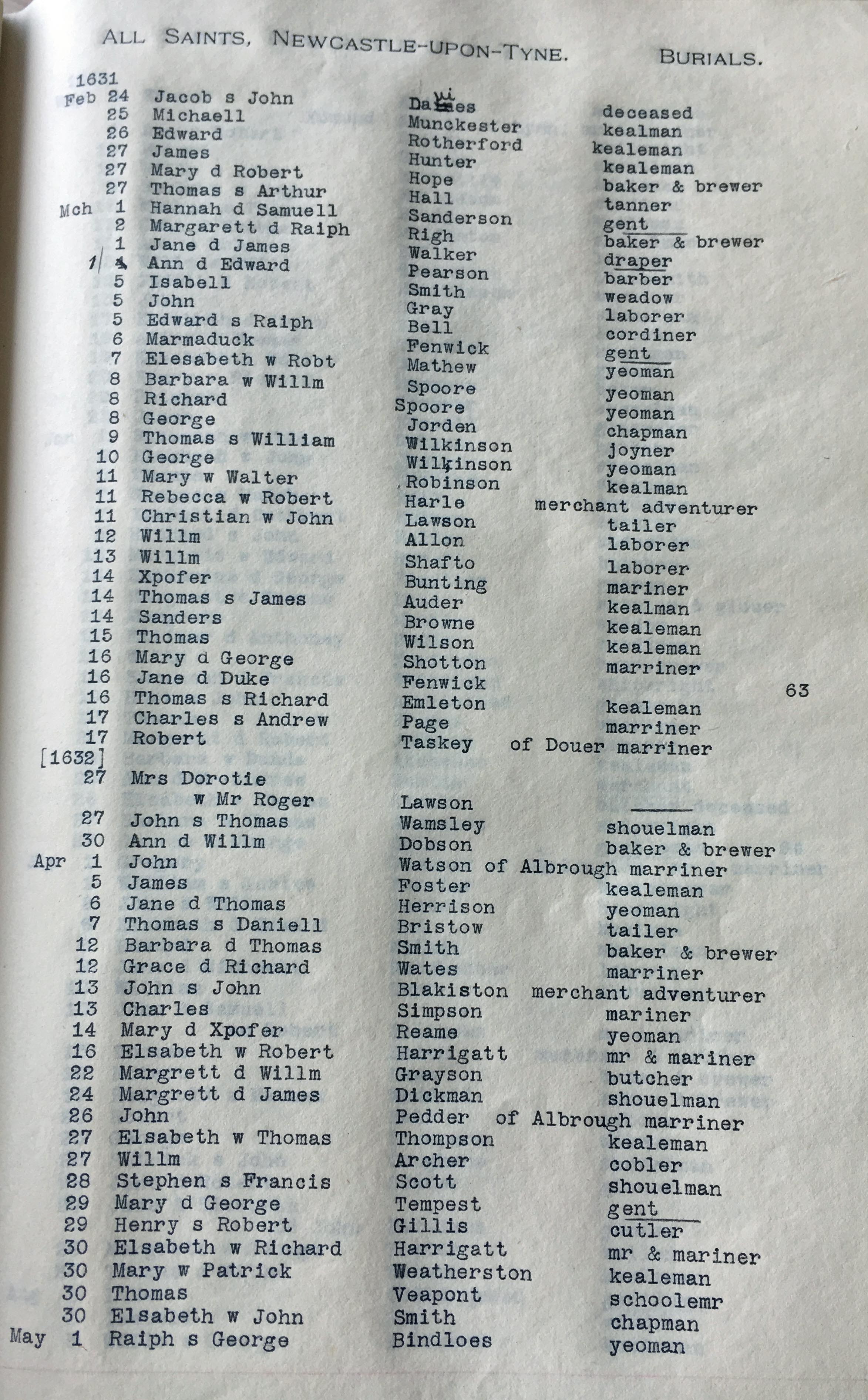

But on 26 March 1632, aged 52, after 6 months illness, ‘a languishing consumption or cough of the lungs’, Dorothy died. The following day, according to her biographer, one of her sons invited the local gentry to dinner and, the day after, the poor of the neighbourhood were served with meat and given money. Her body was then carried to her own boat, which ‘accompanied by at least 20 other boats and barges, and above twice as many horse’ sailed towards Newcastle where ‘they found the streets shining with tapers, as light as if it had been noon’.

‘The magistrates and aldermen, with the whole glory of the town, which for state is second only to London, attended at the landing place to wait on the coffin, which they received covered with a fine black velvet cloth and a white satin cross, and carried it to the church door, where with a ceremony of such civility as astonished all (none, out of love for her and fear of them, daring to oppose it), they delivered it to the Catholics… who… laid it with Catholic ceremonies in the grave….’ (at All Saints Church, an Anglican church).

Charles I

National politics at this time might have been a factor in the liberal response of the authorities to Dorothy’s burial ceremony. Charles I was now on the throne and, at this point, seemed to be quite tolerant of Catholicism and even accused of being too close to non conformists.

Four years earlier he had prorogued parliament, whereupon MPs held the speaker down in his chair so that the ending of the session could be delayed long enough for resolutions against Catholicism and other matters to be read out and acclaimed by the chamber. Charles responded by dissolving parliament and had nine parliamentary leaders imprisoned over the matter turning them into martyrs. (Certain parallels with today became apparent in the course of this article being finalised!)

The year after Dorothy’s death, however, Charles appointed a new Archbishop of Canterbury and together they initiated a series of reforms aimed at ensuring religious uniformity. The courts once again became feared for their censorship of opposing religious views. There were riots and unrest when Charles attempted to impose his religious policies in Scotland. There were difficult times ahead for both Charles and Catholics.

Legacy

Naturally, miracles were attributed to Dorothy: her husband was said to have seen her in two places at once (working in the kitchen and at prayer in the bedroom) – though that would presumably have entailed him being in two places at once too! Her music was heard after her death and her rosary beads were said to have restored a sick woman to health.

It’s difficult to know the exact details of Dorothy’s life – and we haven’t yet even found any portraits of her or her husband, Roger Lawson, or illustrations of Heaton Hall or St Anthony’s at this time – with contemporary impartial writing or even modern research about those with religious convictions not easy to find, but Dorothy seems to have been a strong, capable woman whose bravery at a time of religious persecution not generally considered to have been in doubt. She features prominently in academic works about this period and yet is forgotten in her own neighbourhood. As an early notable one time female resident of Heaton, we believe she deserves to be better known.

Can you help?

If you know more about Dorothy Constable, Roger Lawson or their family especially any contemporary images, we’d love to hear from you. Please either leave a reply on this website by clicking on the link immediately below the article title or email chris.jackson@heatonhistorygroup.org

Acknowledgements

Researched and written by Chris Jackson, Heaton History Group.

Sources

A Biographical Encyclopedia of Early Modern Englishwomen: exemplary lives / edited by Carole Leevin, Anna Riehl Bertolet, Jo Eldridge Carney; Taylor and Francis, 2016

Castle on the Corner: Heaton Hall and King John’s Palace / Keith Fisher, 2013

https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1604-1629/member/constable-sir-henry-15567-160

Hi Chris. This is a great article… thank-you.

Originally, the land between the railway line and Shields Road was part of the Byker Barony. Before the Lawsons left Heaton Hall and the Fenwicks moved in, they relinquished that parcel of land and it was added to the Heaton Hall estate. So, the general opinions of local folk in recent memory, who have always regarded both sides of Shields Road as strictly Byker, are actually echoing factual ancient history: it was Byker all the way up/down to the Railway.

On a separate note: I have no definite proof of this declaration, but I am personally convinced that Heaton Chapel (which subsequently became known as King John’s Palace and more recently The Camera of Adam of Jesmond) was destroyed during Henry VIII’s time. I could find no reference to Heaton Chapel beyond the Reformation other than as a ruin. The conjecture that declared it destroyed by locals in retribution for Adam’s bad behaviour is erroneous… like a lot of historical myths; it actually became a religious building; then more latterly a farm house; until recently it became a tennis court… go figure!

By email from Dave King:

I just enjoyed reading your piece on Dorothy Lawson.

You asked for any further info in the Lawson family. I have been working on some Star Chamber cases from the 1590s/ early 1600s, which may be of interest:

Ralph Lawson et al v Randall Fenwick of Newcastle, Robert & Henry Mitford et al & cross bills, regarding disputed rights to mine coal on Heaton Banks, disputed between Heaton & Byker.

There are several documents, as the Star Chamber records are not rationally organised by case, a summary can be found at http://www.uh.edu/waalt/index.php/STAC_Lawson_et_al_v_Mitford_et_al with links to a number of transcriptions. The depositions in particular may be of interest to you.

2. Brandling v Dent et al. Although not specifically involving the Lawsons, the Dents were their tenants. Some really interesting stuff in here about mining around and under the Ouseburn on the boundary of Byker & Jesmond. In this case I have not produced a summary yet, but transcriptions of documents can be found at the below locations, and again, depositions may be of particular interest. mention of quarries, the Ouseburn flooding coal pits, and even of deponents walking under the river through connecting pits rather than walk the long way round via the bridge.:

http://www.uh.edu/waalt/index.php/STAC_5/B41/40

http://www.uh.edu/waalt/index.php/STAC_5/B72/12

Hope this is of some interest

Really interesting to see such early mentions of coal mining in and around Heaton and get small insights into life (and disputes) here.

Received by email:

I enjoyed your article on Dorothy Lawson and had already read about her online, since Ancestry seemed to think I was a direct descendent of her and her husband. This was fascinating to me as I live in Heaton, but am unconvinced by the claim made by people on Ancestry.

The claim appears to have been made by a genuinely direct relative of mine, John Lawson of Whitby who claims this lineage for our family, through his father or grandfather, Philip Lawson of Egton and Whitby.

John was so convinced of this link, that he called himself Sir John Lawson (Bart) saying that this title had been fraudulently taken off our family and passed down a female line, who had to change their family name to Lawson, in order to keep the title and the estates.

I wonder if there could be any truth in this?

I have tried in vain to find birth records for either John or Philip Lawson, who were born in a time of Catholic Recusancy, so am unable to trace anything further back than their own marriages. I had given up, but your article inspired me to at least ask you if you knew anything about this claim?

Many thanks and I look forward to your reply.

Frances Morgan.

Can anybody help Frances?

Thanks Chris. Fascinating! John Davidson

Thank you for this great article Chris, I am a direct descendant of this great lady, as my paternal Grandmother was a Lawson here in America. This is a great piece of information that was not available to us as readily 30 years ago. Thank you Sir.