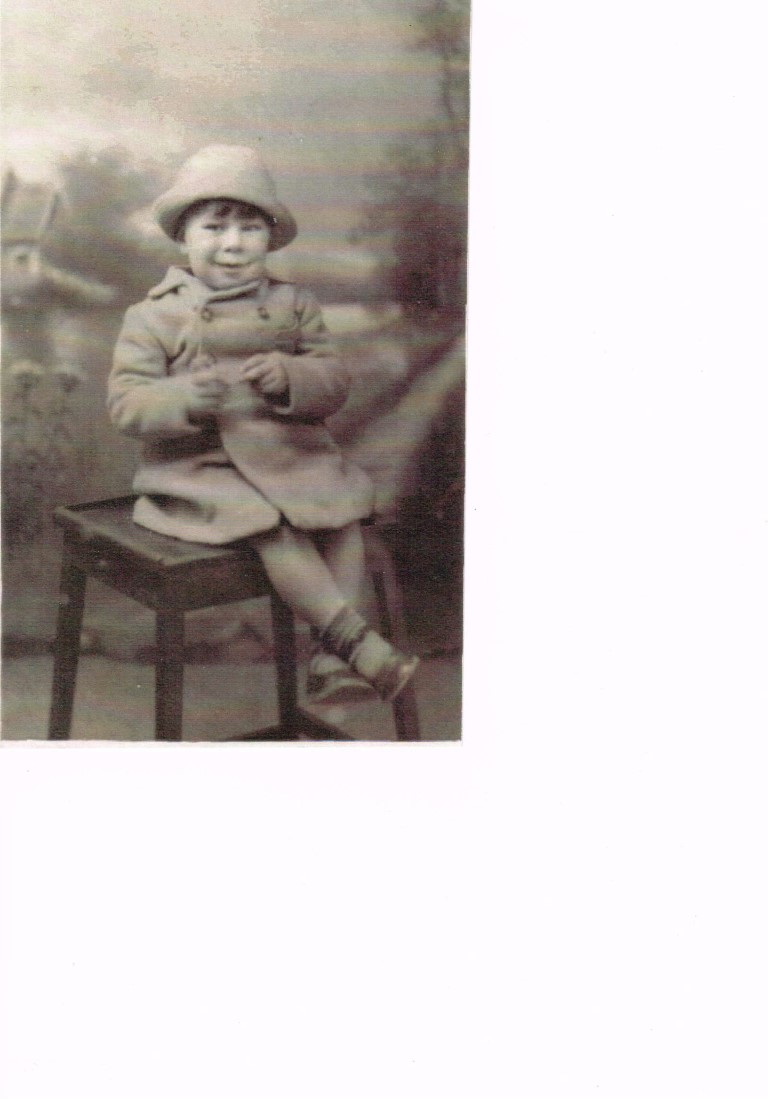

Stories of women and children hurriedly gathering a few belongings together and leaving the home they know to escape the horror of war, only to find themselves once more in the midst of it, have become only too commonplace in 2022. Heaton History Group member, Mike Summersby, arrived in Newcastle as a three year old in 1941 under just those circumstances.

We are delighted to be able to publish some extracts from the memoirs Mike has recently written. Here, he remembers those early days in Heaton, the family’s new home in Mowbray Street and the underground shelter where the family spent many hours:

‘ The wailing siren warned of the attack. Searchlight beams danced across the night sky, seeking out their prey. The dull drone of the planes heightened the sense of fear. Were they ours or theirs?

People hurried from their homes to the row of reinforced concrete air-raid shelters that sat between the Tyneside flats on either side of Mowbray Street. Hurriedly dressed over nightclothes, some carried books, or food, or other comforts. It could be a long night in the shelter.

It was 1941. Jessie Summersby (Mam) and her two sons – my brother Peter aged twelve and me aged three – had only days earlier arrived in Newcastle. Dad was serving in the army. Mam knew not where, except that it was probably somewhere overseas.

As a wartime street warden, Mam had witnessed close-up the horrors of the London blitz. Near breaking point, she and her boys had left the capital as evacuees. After a brief stay in the Wiltshire village of Little Somerford, she had moved us to Newcastle, her childhood home, where her father and her twin sister lived.

From her London home she had watched aerial dogfights between the RAF and the German Luftwaffe. She could tell from the sound of the engines which planes were ours and which were theirs.

Our new home

Our new home was a single room in a downstairs two-bedroom Tyneside flat at 164 Mowbray Street, Heaton (now, but not then of course, opposite Hotspur Primary School) in which my grandfather, William Newton lived with his ‘housekeeper’, Mrs Montgomery.

Mam, my brother Peter and I were given the front room. I assume all concerned hoped that it would be a temporary measure. But these were uncertain times. No one could know how long the war would last. As it turned out this one room was to be our home for the next four years.

We also had use of the scullery, including a shelf in the larder, and access to a shared outside lavatory (colloquially the ‘netty’) next to the coalhouse in the small, red-brick-walled back yard.

So it was that 164 Mowbray Street became the place of some of my earliest recollections and our family home until the end of World War 2.

Being only three years old when we first arrived in Newcastle, I had no awareness of our previous home in London. Nor could I possibly, at that young age, be aware of the sense of loss and deprivation that my mother must have felt as she came to terms with her new situation.

Now, as I reflect on that time and the years that followed, I can only marvel at how brave and resourceful she was, and how magnificently she coped single-handedly during the next four years bringing up her two boys in such strained circumstances.

Mam did her best with what she had. Out of necessity she quickly settled us in. Typical of the front room of a Tyneside flat, our room was roughly thirteen feet square with two alcoves, one either side of a chimney breast. The sash windows looking out onto the front street were curtained with blackout material.

Furniture was basic and second hand or improvised. Much of the floor space was taken up by a three-quarter size bed initially shared by mam, Peter and me, and a square table and two horsehair-covered chairs (rough on the legs of a young boy wearing short trousers).

Later, Peter slept on a camp bed which was folded away each morning and set up in front of the window each evening. I marvel now that without complaint, and for much of our four years living in that room, he slept so many nights on canvas stretched on a wooden frame. Perhaps it felt like camping out but it could not have been comfortable, particularly for a growing teenager.

The two alcoves were used for storage of all our worldly goods, including the less perishable items of food. Orange boxes served for shelving. Mam hand-sewed hems on pieces of cretonne curtain which she then suspended on string across the front of the boxes to hide the contents. The wood floor was covered with faded patterned linoleum that had seen better days and was cracked in places where the floorboards were uneven, which made it difficult to keep clean. Heating in our room was an open fireplace with an iron grate. Teasing a fire into flame on a chilly night required the careful layering of paper, sticks of firewood and coal. One of Peter’s regular jobs was to buy and fetch coal from the coal yard next to the nearby railway line.

Lighting was by gas from a pipe at the centre of the ceiling. When the gas was turned on, a replaceable mantle fixed to the end of the gas fitting glowed when it was lit with a match or a lighted taper. The flow of gas, and thus the brightness, was regulated by the manipulation of pull-chains attached to the light fitting. The mantles were very fragile and frequently needed replacement. The gas mantle would be lit only when the light was intended to be left on – otherwise a candle or a torch would be used as a short-term temporary light – like when someone needed to use the chamber-pot (kept under the bed) for a nocturnal pee. Whatever the form of lighting, it had to be blocked by curtains or screens so that no light could be seen from outside. Stray lights could assist enemy bombers in locating or confirming target areas. The ‘blackout’ was enforced by patrolling Air Raid Precautions (ARP) wardens who would promptly order ‘Put that light out’ if it wasn’t properly screened.

The netty was a cold, stark, forbidding cupboard of a place housing a wooden platform straddled across its width, with an appropriately shaped opening above the lavatory bowl. Faded whitewash decorated the otherwise bare brick walls. ‘Toilet paper’ was squares cut or torn from newspapers, each square punched in one corner, threaded with string and hung in a swatch on a nail. Mounted precariously above the facility was a rusted metal water cistern from which hung a similarly rusted metal chain. The cubicle was little wider than the wooden entry door with its gaps at top and bottom – presumably for ventilation. Ceiling cobwebs added to the sense of gloom. This was a grim place of necessity in which to spend the least possible time, particularly during the winter months.

The Culvert

We had left London to escape the blitz but Mam soon found that the air raid threat, though less intensive than in the capital, was a fact of life here in Newcastle, too.

During our first year living at 164 Mowbray Street we spent many hours in the culvert. After a night spent there, Peter always liked to prolong his stay in order to avoid going to school, or at least to provide him with an excuse for arriving late. Grandad didn’t use the culvert or the street shelters. He preferred to stay in his home, taking refuge in the cupboard underneath the stairs of the flat above.

About a third of a mile long, the Ouseburn Culvert had two entry points. The preferred access for us was down in the Ouseburn Valley off Stratford Grove West. The other – which we never used – was under Byker Bridge.

The Culvert was our place of refuge many times during World War 2. At the wail of the air raid siren we would stop whatever we were doing, grab our gas masks and run out into the streets in the direction of sanctuary. There was no street lighting to guide us if it was a night raid and, anyway, moonlit nights were a mixed blessing. If you could see, you could be seen.

Once inside the Culvert we felt safe. An elliptical structure 6 metres high and 9 metres wide, with a concrete platform floor, it was dry and had the space for distractions and facilities to make the experience tolerable. A canteen, a first aid post and sick bay, bunk beds, an area for worship, a stage for performance, a library, and tolerable – if basic – toilet facilities.

One particularly memorable evening the wail of the air raid siren sounded just a couple of minutes after we had returned to our room from a trip to the fish and chip shop on Stratford Road. Fish and chips were a hugely popular takeaway meal, especially as they were not subject to food rationing. As usual we’d had to stand in a queue to wait our turn at the counter. Then, with happy anticipation of the meal ahead, we carried the hot, newspaper-wrapped bundles the short distance back to our room in Mowbray Street. As soon as Mam had unwrapped the feast, off went the siren. We hurriedly dressed, grabbed gas masks and without a second thought Mam loosely gathered up the fish and chips in their newspaper wrappers and we all ran towards the Culvert. Sadly, on our arrival at our safe haven there was very little left of our now barely warm meal. Most of it lay scattered along the pavements between Mowbray Street and our sanctuary.

Whilst the Culvert offered safety from whatever mayhem might be going on above ground, the overriding but generally unspoken fear was of what would happen if bombs were dropped at either end of the tunnel. Otherwise the occupants were sufficiently protected in their underground location, with its cleverly designed inner blast walls, to offer safety for up to 3,000 residents for as long as it might be needed, until the ‘all clear’ siren was sounded.

Street shelters fell into disfavour after a number of people were killed or maimed as a result of direct bomb hits, in some cases resulting in the concrete and reinforced steel roofs collapsing on the people inside. It turned out that the Ouseburn Culvert was probably our safest option after all.

The culvert was originally constructed to cover a section of the Ouseburn, a tributary of the River Tyne, through a valley which then would be infilled to provide improved access between Heaton and the city centre. (You can read much more about its construction and history here.)

Today, much is rightly made of the Victoria Tunnel, an underground waggon-way built in the 1840s to carry coal between Leazes Main Colliery to the waiting ships on the River Tyne. Longer than the Ouseburn Culvert, it was not as spacious in section but, like the Culvert, it was converted for use as an air raid shelter during World War 2. Tours of the Victoria Tunnel give visitors a graphic interpretation of the sounds of war and the conditions under which people sought shelter from the bombing raids of the Luftwaffe. If similar reconstruction of World War 2 facilities and other interpretation work were to be carried out at a section of the Ouseburn Culvert, it would make a very impressive addition to Newcastle’s heritage offer.

I’ll tell you more about my memories of growing up in Heaton during and after the second world war anon.’

Acknowledgements Thank you to Heaton History Group member, Mike Summersby, for permission to publish this extract from his memoirs. We plan to feature more over the coming months.

Originally published on 19/07/2022

RE: War-time piece. Mike Summersby.. Mike has it right. A very good piece. I must be nearly the same age, b 1938. A bomb fell on Forsyth Road, the next one in a chain on Heaton Secondary School caretaker’s house. My Mum and I were under the stairs in Lavender Gardens before the street shelters were built. My autobiography, Distant Times: Life on Tyneside in the nineteen fifties was published in June 2022.