In January 1804, a list of 50 Heaton Colliery employees was submitted to the government. It was recommended that ‘in the case of actual invasion’ these men drive the horses already offered for use by the artillery. So what was going on? Was Heaton in danger? If so, at whose hands?

In 1804, Britain had been almost constantly at war with France for more than a hundred years: the dynastic wars of most of the eighteenth century were succeeded by more ideological conflicts towards the end of that period.

In late 1797, the then 28 year old Napoleon Bonaparte had declared ‘[France] must destroy the English monarchy, or expect itself to be destroyed by these intriguing and enterprising islanders… Let us concentrate all our efforts on the navy and annihilate England. That done, Europe is at our feet.’ A few months later, Napoleon’s army was massed on the French coast.

Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger called the country to arms.

So it’s understandable that places on the south coast were on a war footing, but Heaton?

Aborted Invasion

Actually the people of the north-east had every reason to be afraid. Just seven years before, the French General Lazare Hoche had embarked upon an invasion of Britain and, despite its distance from the English Channel, Newcastle was at the very heart of his plan. This was just seven and a half years after the storming of the Bastille and four years after the beheading of Louis XVI, a period of great turmoil in France and elsewhere in Europe.

In Ireland, the Society of United Irishmen has been formed with a stated aim of achieving ‘an equal representation of all the people’ in a national government ie an overthrow of British rule. The society supported the aims of the French revolutionaries and the French First Republic supported their Irish comrades.

Hoche’s plan was for a three-pronged attack on Britain: there would be two supplementary attacks to create diversions while the main force was landing in Ireland. But bad weather changed the course of history. In December 1796, storms meant that Hoche’s main fleet was unable to land in Bantry Bay in south west Ireland. He eventually gave the order for a return to France.

Meanwhile one of the smaller diversionary forces set sail for Newcastle but further gales in the North Sea, together with poor discipline and instances of mutiny, meant that these ships also returned to France. The original plan was for the invaders to march from the Tyne to Lancashire. Even if they’d landed successfully, that might not have gone well in the middle of a northern winter!

The only part of the plan to meet with some (albeit very limited) success was that for a second diversionary force to invade Wales. As you may remember from your history lessons or pub quizzes, in February 1797, four French warships managed to land in Fishguard, the last time Britain was invaded. However, the French force’s Irish-American commander, Colonel William Tate was soon forced to surrender by a combination of locals and a hastily deployed national response. A planned march on Bristol never took place.

But you can appreciate why the whole country was nervous including, or especially, people in and around Newcastle.

Technology

This fear was not lessened when, in November 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte, who had issued the threat referred to at the beginning of this piece, seized control of the French parliament and militia in a coup d’état.

Like Hoche before him, Napoleon didn’t limit his stated ambitions to an attack on the south coast:

‘It would then be possible to transport to any desired spot in England 40,000 men, without even fighting a naval action if the enemy should be in stronger force; for while 40,000 men would threaten to cross in the 400 gunboats and in as many Boulanger fishing-boats, the Dutch squadron, with 10,000 men on board, would threaten to land in Scotland,’ he wrote in 1798.

Not only did he put 50,000 men to work on enlarging ports on the north coast of France so that he could gather a huge army there, he also ring-fenced 10,000 francs to support the invention of new warfare technologies such as submarines, balloons and rockets.

Among the inventors working in France was American Robert Fulton. He had previously worked for the Duke of Bridgewater in Cheshire. While in England, Fulton wrote a treatise on canal construction in which he suggested improvements to locks and other features and built what may have been the world’s first steamboat.

In 1797, however, Fulton had left England to study in Paris where he built further steam boats, experimented with torpedoes and designed what is considered to have been the world’s first practical submarine ‘Nautilus’. The French government granted him permission to build it and in July 1800 it was launched on the River Seine in Rouen. In July 1801, at Le Havre, Fulton took Nautilus down to the then-remarkable depth of 7.5m. With his three crewmen and two candles burning, Fulton remained underwater for an hour. When he added a copper ‘bomb‘, a globe containing 25.7 cubic metres of air, the time a crew could spend underwater was extended to over four and a half hours.

Rumours of these unimaginable technological advances quickly spread around Britain and concern escalated.

There were even rumours that Napoleon was already in Britain. One traveller, James Neil, wrote about a belief in Wales that Napoleon had escaped from France and was hiding in the mountains ‘so they eye every stranger particularly; and (would you believe it) absolutely took me for the First Consul… They say he was born in Wales and that two of his brothers were transported.’

Defence

As early as 1796, the British had a ‘scorched earth’ policy. There were plans to evacuate civilians, especially more vulnerable people, then rip up roads and bridges and destroy food, livestock and vehicles before the enemy could take advantage of them. Beacons, watch-houses and other coastal defences were built.

In March 1803, following the short-lived peace which followed the Treaty of Amiens, Lord Hobart, the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, wrote to the Lord Lieutenant of every county accompanied by a detailed plan for recruiting, training, arming, feeding and paying a volunteer militia. Just four months later, the Army of Reserve Act came into force: ‘The King must needs resort to his prerogative of compelling all his subjects to take arms’. Men aged 18 and 40 years old were to be levied by ballot. Parishes could be exempted if they furnished a large number of volunteers.

In many places, the number of volunteers far outweighed the capacity to cope with them, resulting in petitions from people all over the country who believed a larger force was needed to defend them. Politicians, soldiers, businessman and bishops vied with each other to rouse the nation and be seen as the most patriotic.

‘Every town’ wrote George Cruikshank ‘was, in fact, a sort of garrison – in one place you might hear the tattoo of some youth learning to beat the drum, at another place some march or air being practiced on the fife and every morning at five o’clock the bugle horn was sounded through the streets to call the volunteers to a two hour drill…’

But many people also fled from places they considered vulnerable to attack. On 13 October 1803, classical scholar Thomas Twining wrote:

‘I suppose you will not ask me why I leave Colchester. I leave it because I am afraid to stay in it. Many have left, more are preparing to leave it: though I myself think there is very little danger, yet I should be uneasy to stay here and run the risk…’

Local

But what about the Newcastle area at this time?

‘I can’t quite remember the date but I think it was in 1805 that Miss Jenkyns wrote the longest series of letters; on occasion of her absence on a visit to some friends near Newcastle upon Tyne. These friends were intimate with the commandant of the garrison there, and heard from him of all the preparations that were being made to repel the invasion of Buonaparte, which some people imagined might take place at the mouth of the Tyne. Miss Jenkyns was evidently very much alarmed; and the first part of her letters was often written in pretty illegible English, conveying particulars of the preparations which were made in the family with whom she was residing against the dreaded event; the bundles of clothes that were packed up ready for a flight to Alston Moor (a wild hilly piece of ground between Northumberland and Cumberland); the signal that was to be given for this flight, and for the simultaneous turning out of the volunteers under arms; which said signal was said to consist (if I remember rightly) in ringing the church bells in a particular and ominous manner. One day when Miss Jenkyns and her hosts were at a dinner-party in Newcastle, this warning-summons was actually given (not a very wise proceeding , if there be any truth attached to the fable of the Boy and the Wolf; but so it was)…’

That passage appears in Mrs Gaskell’s novel ‘Cranford’. Elizabeth Gaskell (née Stevenson) wasn’t born until 1810 but she will have heard stories about such recent history, including from her many connections in Newcastle. As a young woman, she stayed with William Turner and his daughter, Ann, for several lengthy periods between 1829 and 1831. Turner is best remembered locally as the founder of the Lit and Phil in 1793 and he was extremely well connected. Elizabeth Gaskell’s letters reveal that she had a wide circle of friends and acquaintances in the city from whom she could have learnt about this period. Indeed we know that on 1 February 1804, the burning of whins on the Lammermuir Hills was mistaken for an invasion and caused the alarm to be raised across Northumberland and as far south as Durham. This could well be what Mrs Gaskell was referencing in ‘Cranford’.

Napoléon Bonaparte (‘Buonapartè 48 hours after landing’) by James Gillray, published by Hannah Humphrey, hand-coloured etching, published 26 July 1803 (Thank you to the National Portrait Gallery, London)

Two of the great legacies of the period of ‘The Great Fear’ are cartoons, such as the one above, and popular songs of the period. The recall of one reported incident in particular continues to go down well on Tyneside even today. The contemporary ditty ‘The Baboon’ recalls how an animal that had escaped from a circus in Hartlepool was taken to be a French soldier. Other songs about this apparent case of mistaken identity were written after the event, including Ed Corvan’s ‘The Fisherman Hung the Monkey, O!’. This is the original:

‘Tom flag doom his pipe, an’ set up a great yell;

He’s other a spy, or Bonnypairty’s awnsel:

Iv a crack the High Fellin was in full hue and cry,

Te catch Bonnypairt, or the hairy French spy.’

Preparations

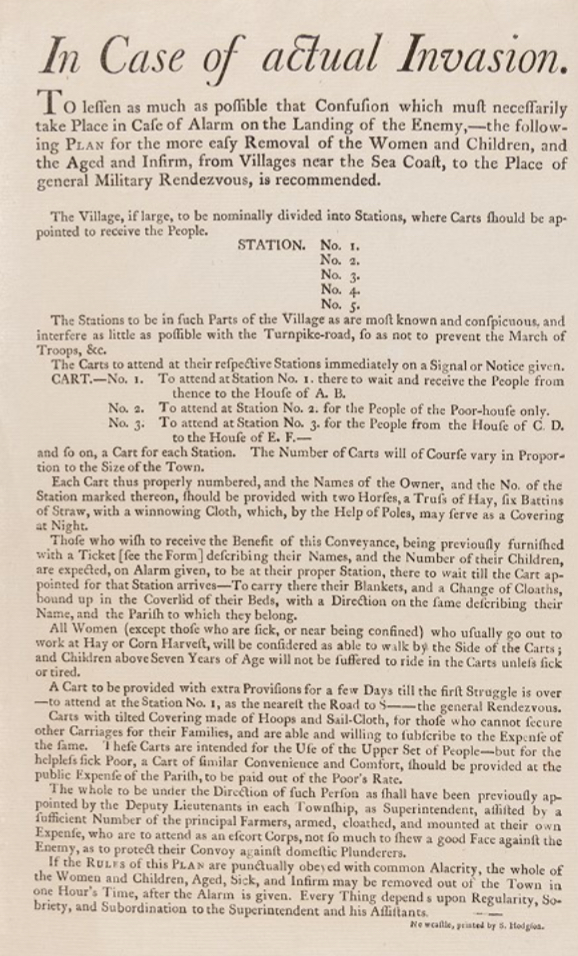

The above broadsheet, undated but printed in Newcastle during the ‘Great Fear’, gives instructions for the ‘more easy Removal of the Woman and Children, and the Aged and Infirm, from Villages near the Sea Coast, to the Place of general Military Rendezvous’. It states that the evacuation should ‘interfere as little as possible with the Turnpike-road, so as not to prevent the March of Troops’. The turnpike road referred to is the road between North Shields and Newcastle, a toll road opened around a quarter of a century earlier, which we know as Shields Road. In the case of Napoleon invading via the Northumberland coast, the defending army would have passed immediately to the south of Heaton.

The evacuation plans were highly organised. A series of ‘properly numbered’ carts would wait at pre-arranged points to collect designated people who would have previously been ‘furnished with a Ticket… describing their Names, and the Number of their Children’. They were expected to make their way to their designated station on the sounding of the alarm. The cart owners were expected to provide ‘two Horses, a Truss of Hay, six Battins of Straw, with a winnowing Cloth, which by the Help of Poles, may serve as a Covering at Night.’

‘All Woman (except those who were sick or near being confined) who usually go out to work at Hay or Corn Harvest, will be considered as able to walk by the side of the Carts; and Children above Seven Years of Age will not be suffered to ride in the Carts unless sick or tired.‘ They were expected to assemble carrying their blankets and a change of clothes, ‘bound up in the Coverlid of their Beds’.

‘The Upper Set of People’, who were unable to secure tickets for these publicly funded carts or ‘secure other Carriages for their Families’ could pay a subscription to allow them to travel on ‘Carts with tilted Coverings made of Hoops and Sail-Cloth’.

The convoy would be under the direction of someone ‘previously appointed by the Deputy Lieutenant in each Township, as Superintendent, assisted by a sufficient Number of the principal Farmers, armed, cloathed and mounted at their own Expense, who are to attend as an escort Corps, not so much to shew a good Face against the Enemy, as to protect their Convoy against domestic Plunderers.’

The broadsheet concludes ‘If the RULES of this PLAN are punctually obeyed with common Alacrity, the Whole of the Women and Children, Aged, Sick and Infirm may be removed out of the Town in one Hour’s Time, after the Alarm is given. Every Thing depends upon Regularity, Sobriety, and Subordination to the Superintendent and his Assistants’.

Sympathisers

The north-east seemed to be well-prepared. But it would be wrong to think that Napoleon did not have supporters in England. Many of these were anti-monarchists and Whigs who did not want to see the Bourbons restored to power. Others, romantics like Lord Byron, who saw Napoleon as a heroic figure for his bravado, strength, cleverness, charisma – and republicanism. Newcastle’s William Burdon, a writer and early sympathiser, had already (in 1804) written a biography of Napoleon.

But plenty of ‘ordinary’ people too appreciated what Napoleon had done for the French people, certainly in later years: Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt (best known for his involvement at Peterloo), in a 1821 speech, claimed that sheep farmers on the River Coquet wanted to send cheese to Napoleon on St Helena. And Ferryhill born John Stoke was Napoleon’s doctor for a time on Elba and went on to work for his brother.

Heaton Colliery

This is the context in which this list of ‘Men and Lads, employed at Heaton Colliery under Messrs Johnson Row and Co, who have been accustomed to drive Horses, and who are, in case of actual Invasion, recommended to drive the Horses offered to Government by the said Messrs Johnson… for the use of the Artillery, viz Fifty Effective Horses provided with Bridles, Brougham’s [a collar for a draught horse], Hamsticks, Traces and Collars’ was written in January 1804.

In 1791, George Johnson, the then viewer of Byker Colliery, and William Row, a Newcastle merchant, referred to in the above document, along with William Smith, a gentleman of Plessey, had leased Heaton Colliery for a period of 31 years for an annual fixed rent and an additional tentacle rent based upon the production of the colliery.

The document doesn’t indicate which military unit the miners offered to the government would be attached to but volunteer corps in the area included the Southern Regiment of the Northumberland Local Militia, commanded by Colonel Commandant Charles William Bigge, who lived at Benton House in Benton; and the Newcastle Armed Association, a government supported unit some 800-1000 men strong, commanded by Sir Matthew White Ridley 2nd Baronet of Heaton Hall, who was also the landowner and owner of the surface rights at Heaton, so this sounds the most likely destination for the Heaton Colliery men.

Incidentally, it was an agreement in 1792 between Johnson and partners and Sir Matthew White Ridley, which allowed the colliery to build a waggonway but which specifically the partners were ‘not to erect and Pitmen’s or other Houses on any part of the Heaton estate.’ This explains why no colliery village existed in Heaton and why most Heaton miners lived in places like Bigges Main and the lower Ouseburn right up to the mid 19th century.

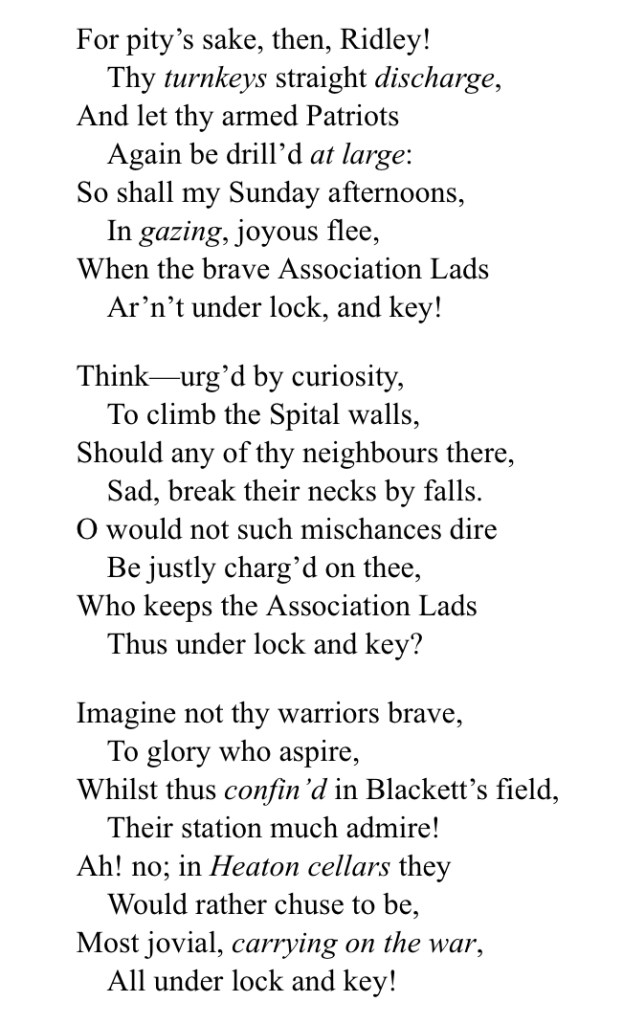

A song ‘Blackett’s Field’ by John Shield of Newcastle, written in late 1804, attacked the way Newcastle Armed Association volunteers were treated at drill by Ridley. The song claims that the soldiers would rather be drinking in ‘Heaton’s cellars’ (but this appears to refer to a pub rather than our township, in which as we have just seen, few people then lived) than marching.

Horsemen

We don’t know how the fifty Heaton Colliery horse handlers felt at being volunteered for service. It may well have been considered a preferable alternative to conscription, which could easily have been the fate of the men. And that may have been the view of Johnson and Row too. Far better to have the miners close to hand and perhaps able to work, and so make a profit for the owners, when they weren’t training than losing them altogether for potentially a long period of time.

Because most of the names on the list are common and there are no further biographical details plus the fact that pitmen of that period were surprisingly mobile, it’s been difficult to find out more about them.

We know that none of the men died in the Heaton pit disaster 11 years later and none were interviewed by the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Children’s Employment in 1841 but, to date, we have found out more about only a few of them. We can say with a reasonable degree of confidence that:

William Atthey was born about 1784 in Wallsend so would have been c 20 years old in 1804. He married Mary Wandless at All Saints, Heaton’s parish church at that time, on 18 June 1808. We find him again in the 1841 census by which time he was 55 and living with Mary and 5 of their children in Easington, County Durham. He was buried on 20 July 1849 in Wingate, Durham.

Godfrey Harper was baptised on 18 May 1783. His name appears in St Andrew’s Non-conformist parish register. He was married in Wallsend on 25 August 1821. In 1841, aged 58 and a widower, he was still a coal miner, living in Willington with three young children. An announcement in the ‘Newcastle Courant’ reported that he had died on 2 April 1850 aged 67.

Thomas Magnay was born in Wallsend c 1786 and married Alice Waggit on 9 January 1809. In 1841, he, Alice and 6 children were living in Wrekenton with their six children. By 1851, they were living in Easington, Co Durham with 2 children still at home and, perhaps surprisingly, a live-in servant. He was still working as a coal miner. Their surname was by now written as ‘McNay’.

Edward Magnay married Mary Bowman on 21 May 1809 in All Saints Church. In 1851, aged 65, he was described as a ‘retired miner’ and still living with Mary, now in Shildon. Their son, William, an engineer, was still at home. They retained the ‘Magnay’ spelling of their name.

However, baptismal, marriage and burial records from All Saints Parish include people with most of the 50 names on the document. It’s just not so far been possible to definitively associate them with the volunteered colliers.

Trafalgar

However, on 21 October 1805, only 21 months after the colliers had been offered to the government, the threat of invasion was over. The British fleet under the command of Lord Nelson and, after his death, the Geordie, Admiral Collingwood, defeated the Franco-Spanish fleet off the south-west coast of Spain.

A list of employees of Heaton Colliery from 1806 shows that most of the horsemen were still employed and gives an indication of the roles they were now performing. Most were hewers but:

George Cleugh was a sledge driver ie he drove horses that pulled sledges full of coal.

Edward Magnay – an ‘insetter at crane’ ‘ie he was in charge of the crane which lifted the coal onto the rollers

Thomas Magnay – crane man ie he hoisted corves of coal onto the rollers with the aid of a crane

Richard Moor – sledge driver

John Newton – sledge driver

Richard Reed – sledge driver

John Snowdon – sledge driver

Thomas Sowthart – sledge driver

George Unwin – sledge driver

Sand Wilkinson – crane man

William Atthey and Godfrey Harper were not mentioned as being employed in the colliery at this time.

It appears that some sense of normality had returned to Heaton although it would be another nine years before Napoleon was finally defeated at Waterloo, surrendered and was exiled to St Helena where he died in 1821. Over two hundred years later, the French and British generally hold very different views on him, as evidenced by the contrasting receptions in the two countries to Ridley Scott’s recent film.

Acknowledgements Researched and written by Chris Jackson, Heaton History Group. With special thanks to Peter Hicks of the Foundation Napoléon, who sent very helpful information about local people with connections to Napoleon; Alan and Pat Richardson, who helped with deciphering some of the handwriting in the document as well as sharing information about the ownership of Heaton Colliery; the Common Room Library where the colliery documents are archived.

Can You Help?

If you know more about this period in Heaton’s history, we’d love to hear from you. You can contact us either through this website by clicking on the speech bubble immediately below the article title or by emailing chris.jackson@heatonhistorygroup.org

Sources

‘Britons: forging the nation 1707-1837’ / by Linda Colley; 3rd ed; Yale University Press, 2009

‘A Celebration of Our Mining Heritage’ / Les Turnbull; Chapman Research in conjunction with the North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers and Heaton History Group, 2015

‘Great Fear in the United Kingdom, 1802-1805′ ‘/ by Peter Hicks in ‘Napoleonica, La Revue’ Vol 32 Issue 2, 2018

‘A Mad, Bad and Dangerous People? England 1783-1846’ by Boyd Hilton, Clarendon Press, 2006

‘Mrs Gaskell and Newcastle’ / by PJ Yarrow in ‘Archaeologia Aeolian’ Series 5 Vol 20 (1992) p139-146

‘Napoleon and British Popular Song 1797-1822’ by Oskar Cox Jensen; D Phil Thesis, Christ Church, Oxford, 2013

‘Napoleon and the Invasion of England: the story of the Great Terror’ / by HFB Wheeler and AM Broadley; originally published in 1908. Republished by Nonsuch Publishing, 2007