People across America mourned, in November 1986, the loss of 95 year old Dr Fred Olsen. In Heaton, Newcastle, his birthplace, few would have heard of him. So why was he so well-known in the USA?

Home

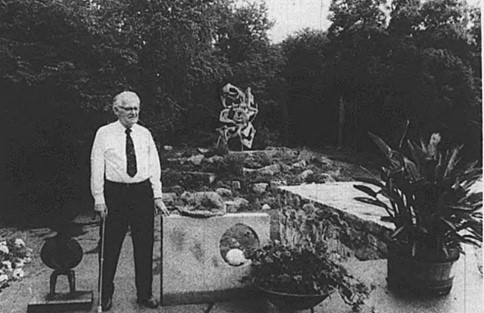

It’s true that, in some circles, the distinctive home he had built in Guilford, Connecticut, on a pink granite outcrop overlooking Long Island Sound was as, if not more, famous than its owner. What became known as the ‘Olsen House’ had been designed by the noted modernist sculptor, painter and art theorist Tony Smith in 1951.

As well as a structure that would take advantage of the location and viewpoint, Olsen had asked for a gallery to display his collection of artworks as well as a place which could hold exhibitions and indeed accommodate the artists themselves. The combination of antiquities and modern furniture, a sunken arena for film shows and a salt water swimming pool were well known features of what became known as ‘the crazy house’. The ‘Shore Line Times’ of 14 July 1955 described the structure as ‘dramatic, being built on stilts, which gives it the feeling of an island in space, remote and secluded’.

Smith designed around twenty private dwellings in the 1950s but the compromises necessary to fulfil a client’s demands encouraged a move back towards his more minimalist public art from the 1960s onward. Indeed, changes and modifications that Olsen had made to the original design of the building within a year or two of its construction were not entirely welcomed by Smith who left the project at that point.

When, in 1998, the house was for sale and threatened with possible demolition, a campaign was launched by Marjorie Olsen (the Olsens’ daughter in law) in order to enable purchase of the house by Jeff Preiss and Rebecca Quaytman who vowed to redevelop but retain the original structure. At this time Terence Riley, chief architecture and design curator at The Modern periodical, ranked the house ‘among the best examples of post-World War 2 American domestic architecture.’

Modern Art

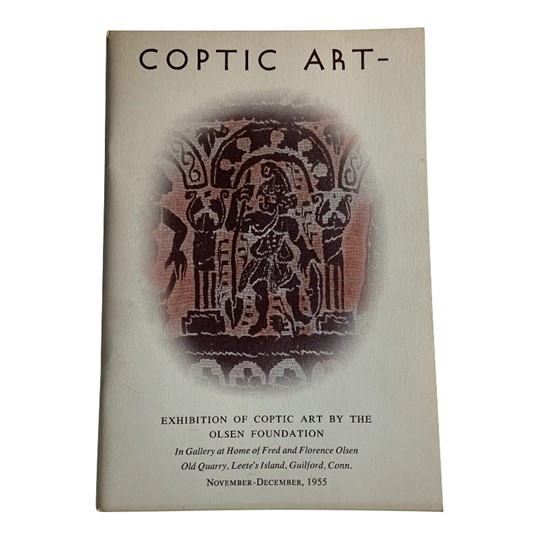

But why did Olsen need galleries in his house? He himself said that his interest in art was whetted when his son gave him a book about the paintings of Paul Klee. This led him to want to know more about the prehistoric and primitive art that inspired them as well as discover more about Klee’s contemporaries.

Not only did he and his wife, Florence, start to buy artworks but they got to know and befriend some of the most significant artists of the mid to late twentieth century including Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock. Fred Olsen purchased one of Pollock’s earliest abstract expressionist paintings for $8,000, the highest price paid for a Pollock at that time. This work has come to be known as ‘Blue Poles’ though initially it was identified merely as ‘Number 11, 1952’. It now hangs in the National Gallery of Australia and demonstrates the Olsens’ importance in encouraging emerging artists. The couple became compulsive collectors.

Archaeology

It was the purchase of a winter home in Antigua on their retirement that enabled Fred and Florence Olsen to embark on another stage of their life. Fred attributed the purchase of the property partly to his preference for warmer climates despite, as he pointed out, his being half Norwegian. However, it can’t have been a coincidence that it also enabled the couple to pursue their long-time interest in ancient civilisations.

They began to journey by canoe through what had been known as the land of the Arawaks, a pre-Columbian civilisation off the coast of South America and along some of the islands in the Caribbean. Despite their relative age, Fred and Florence journeyed along the rivers of Suriname, Guyana and Venezuela – often accompanied by their children and later by some of their grandchildren – looking for Arawak settlements and artefacts.

They supported and took part in the 1973 Yale University expedition led by the renowned anthropologist, Professor Irving Rouse. The scale and significance of the Olsens’ work and discoveries can be illustrated by the long-lasting impact of their subsequent donations of both ancient and modern art, not only from the Americas but Africa and China too, to a number of American universities including Yale, Illinois and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Yale’s University’s collection of art of the ancient Americas encompasses the diverse artistic treasures representing over more than 2,500 years from the Olmec culture to that of the Aztec and Inca Empires. The collection began in the 1950s with a donation from the Olsens and much encouragement from the Yale professor and pioneering art historian, George Kubler. The university website recognises the importance of this financial and moral support by stating, ‘The Olsen collection provided a representative base of Mesoamerican art and established the strength of the collection in the art of the Maya and the cultures of West Mexico, including outstanding Maya ceramic figurines from Jaina Island and striking sculptures and house models from West Mexico’.

Similarly the generosity of the Olsens is evident on the website of the Krannert Art Museum at the University of Illinois. And there are items previously owned by Olsen in British collections too, such as this bowl in the British Museum, although these days legitimate questions are asked as to the appropriateness of museums holding objects which might have been removed from their country of origin without appropriate consent.

But Fred Olsen wasn’t just a collector or even a facilitator of exhibitions. He published two works, ‘On the Trail of the Arawaks’ and ‘Indian Creek’ (University of Oklahoma Press).

Perhaps you’re beginning to see why Fred Olsen’s death was significant across the ‘Pond’? But how did the boy born in a modest terrace in Heaton become able to afford to build a statement house, collect art and retire to the Caribbean to research ancient civilisations?

Beginning

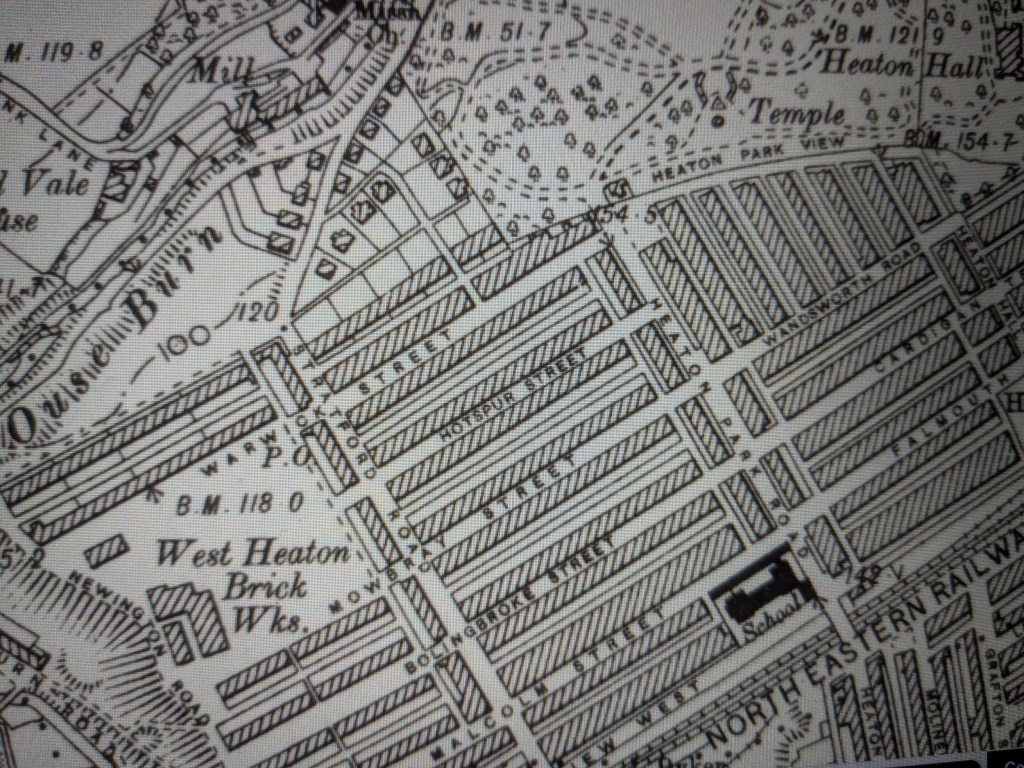

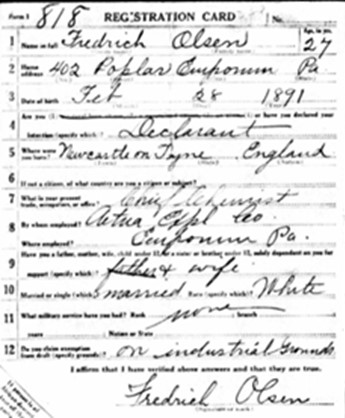

It was on 28 February 1891 that Fred was born to Frederick and Elisabeth Olsen in a downstairs flat at 38 Hotspur Street in Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne. His parents’ marriage was the result of a romantic liaison between a Norwegian sea captain and a local girl and the infant was given the first name of his father, who was working at the time as a stationer’s assistant.

Fred Senior and Elisabeth were clearly aspirational: by the time of the next census in 1901, the family had moved to Jesmond and were soon to make a much lengthier and more challenging excursion. The decision was made in 1906 to emigrate to Canada where the now fifteen year old Fred Junior started work as a member of logging teams. Although his mother’s ambition was for him to go into the church, perhaps his early education at Dame Allan’s School in Newcastle deserves some credit for him instead joining the long list of innovators that have been part of Heaton’s contribution to scientific progress through the centuries.

The Olsen family was not prosperous and a scholarship would be needed to enable further studies. In the field of 3,000 candidates for university entrance, Fred came tenth in classics but, for reasons which he could never explain, first in chemistry. Fred’s first step on the road to his subsequent success and significance was undergraduate study at Toronto University where he gained a degree in physical chemistry.

His first temporary employment after graduation was as a teacher at the Brentha School, north of Ottawa.

The above photograph shows Frederick with a group of his pupils. The girls are sisters of Florence Edith Quittenton who became Fred’s wife on the 28th April 1917.

Science and warfare

During the First World War, Fred Olsen worked briefly in an explosives plant in Quebec but in 1917 he attained his first professional post as Chief Chemist for the Aetna Explosives Company of Gary, Indiana.

Although the end of the war was celebrated throughout the world it did inevitably lead to some economic challenges for any enterprises whose income had been linked to the conflict itself. The sudden bankruptcy of his employers meant that Olsen then moved to Picatinny Arsenal from 1919 to 1929 where he employed his academic knowledge to solve a very practical and potentially lucrative challenge.

The need to manufacture large quantities of munitions for the dreadful demands of the global conflict from 1914 to 1918 meant that, at the end of hostilities, companies were left with considerable stores of materials which no longer had immediate or even likely customers. To understand the significance of Olsen’s innovation it is necessary to comprehend a little of the nature of armaments and their workings.

It is worth remembering how feature films depicting nineteenth century conflict often seem to feature clouds of smoke over the battlefields and combatants. This is testament to the makers of these recreations and their determination to be historically accurate. Before the invention of what is termed ‘smokeless powder’ in the 1880s, the propellant for any firearms or artillery regardless of their size was ‘black powder’ which not only created heavy smoke but also considerable moisture and residue. These were not insurmountable obstacles when the firearms were discharged in a manual and relatively slow fashion which gave time for the individual cleaning and reloading of each weapon. The success of invention and innovation in warfare is something which seems to be a constant if regretful feature of human civilisation and ‘progress’. The appearance, in the late nineteenth century, of semi-automatic weapons which contained a number of moving parts meant that a new type of gunpowder was going to be essential.

The smokeless powder devised in 1884 by Paul Vielle was based upon nitrocellulose which had been employed as the basis of ‘guncotton’ since the 1840s. One of the challenges of materials that are desired for their propensity to ‘explode’ is how they can be kept and stored safely until they are needed. As nitrocellulose was less stable than traditional or ‘black’ powder its use for military purposes was limited. Indeed, a number of guncotton factories had themselves exploded in England and Austria in the mid to late nineteenth century.

The potential of this newly devised material as being a superior and more usable variant of ‘smokeless’ powder was, however, pursued across Europe and the USA in the second half of the nineteenth century. In 1908 the United States Army began the manufacture of its own formula at Picatinny Arsenal.

The challenge facing Dr Olsen’s new employers in 1919 was that large quantities of this ‘smokeless powder’ were stored without any clear idea of when or indeed if they would be required. As it was well known that these materials were likely to grow less stable over time, how could they be kept?

Fred Olsen devised a remanufacturing process to preserve deteriorating military inventories of smokeless powder in artillery ammunition manufactured during the First World War. This led to the development of stable nitrocellulose which could be transported and stored more safely and securely, thus ensuring the longevity and future sale of previously manufactured material.

Such an innovation was bound to begin to make a name for Fred and in 1929 the Western Cartridge Company of East Acton, Illinois hired the now Dr Olsen, from Picatinny Arsenal.

Frederick had already submitted two applications for patents regarding methods both to purify nitrocellulose and prolong its usefulness. In 1933 U.S. Patent #2,027,114 was issued to Western Cartridge Company titled ‘Manufacture of Smokeless Powders’. This radical and novel series of actions became known as the ‘underwater’ process in order to maintain a constant, and safe, environment. The reworked powder was dissolved in a bath of ethyl acetate which became a viscous syrup or slurry which could then be formed into small spheres of nitrocellulose. These balls could be isolated and treated either to increase potential energy (by the introduction of nitroglycerin) or coated with graphite to reduce the speed of ignition. The innovative process which Olsen had perfected demonstrated a number of advantages over other methods. The resultant ammunition was stable for much longer as well as being more flexible in terms of its density and chemistry allowing for a wider range of applications in small firearms and larger artillery pieces.

The intricacies of this manufacturing process demonstrate the scientific knowledge and expertise that Fred Olsen employed in order to solve a long-standing challenge regarding the efficacy and safety of munitions and their propellants. Those of us unfamiliar with the world of weaponry may struggle to comprehend the significance of Dr Olsen’s work but it is worth noting that a current munitions company, Hogdgon Powder, makes mention of his significance on their website as well as frequent mentions within associated periodicals, e.g. ‘Guns and Ammo.’

The Western Cartridge Company became an Olin Corporation subsidiary in 1944 with Fred Olsen taking on the senior role of vice president responsible for Research and Development in February 1952. The announcement of his promotion described Dr. Olsen as being a ‘nationally recognized authority in the chemicals and explosives industries’. It was his success in the armaments industry that made his support for arts and culture in later life possible.

Dr Fred Olsen, industrial chemist, art collector and scholar (as the ‘New York Times’ described him) died on 2 November 1986. He left most of his remaining art collection to American universities.

Legacy

The significance of Fred Olsen for chemistry, and the world of explosives in particular, is further demonstrated by his membership of a number of organisations and societies. These included the Industrial Research Institute, American Chemical Society, American Institute of Chemical Engineers, Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Institute, Canadian Pulp and Paper Association, Engineers Club of St. Louis, as well as the scientific fraternities, Sigma Xi and Tau Beta Phi.

His importance to the art and cultural heritage of the USA and the wider world can be seen in the collections of the galleries and museums to which he was such a generous benefactor.

Finally, when Fred Olsen was asked for an article in ‘The Second Section’, a periodical local to his adopted home of Guilford, Connecticut, whether he would have liked to have lived in another age, his reply speaks volumes about his nature and spirit. He responded, ‘I would really like to have been born fifty years later, so that I could have been an astronaut’ . But his whole life was a journey of discovery that had started out 95 years earlier on Hotspur Street in Heaton and led to recognition in numerous fields, particularly in the USA.

Can You Help?

If you know more about Fred Olsen or have memories or photos to share, we’d love to hear from you. You can contact us either through this website by clicking on small speech bubble immediately below the article title or by emailing chris.jackson@heatonhistorygroup.org

Acknowledgements

Researched and written by Karl Cain of Heaton History Group, employing research carried out by Arthur Andrews, also of Heaton History Group. The article was only made possible by the support and involvement of Tracy Tomaselli, Historical Room Specialist at the Guilford Free Library, Connecticut.

Sources

Census records for both England and the USA

Historic Resource Inventory of Guilford

New York Times

Shore Line Times

San Fransisco Chronicle

University of Toronto Yearbook for 1916

USA official documents including immigration application, marriage certificate and military registration records

Wikipedia

Other online sources

I was married to Fred Olsen’s grandson Fredrich Olsen IV and spent much time at the Olsen home in Guilford, Ct. You mention daughters in the story about dug out canoeing, but Fred and Florence had two children, a son and daughter — Fredrich Olsen III and Elizabeth Olsen. Just thought I’d correct the record. It was lovely to see this article. I knew both Fred and Florence well in their later years. They both remained active and curious into their 90s.

Hello Robin, Thank you so much for taking the trouble to get in touch and to point out the error in the article. We’ll correct that as soon as possible.