At 4.00pm on 11 January 1914, Bert Williamson stood on the frozen Arctic Ocean and, peering through the darkness, saw his ship disappear into a huge crack in the ice to the sound of solemn music. But what was a Heaton man doing in the Arctic in the middle of winter? Where did the music come from? And what happened next?

Early Life

Robert John Williamson was born in Gateshead on 13 August 1878, the son of Eleanor Williamson and her husband, John Tate Williamson, a mechanical draughtsman from Cargo Fleet near Middlesbrough. Robert was the middle child of seven. The family moved regularly with John’s job: in 1881, they were living in Plumstead, London, where they had a live-in servant; in 1891, they were in East Dulwich. By now, John was described as a consulting engineer and traveller (ie a travelling salesman or rep).

The family eventually moved back to the north-east, however, and young Robert (or Bert as he was usually known) served his apprenticeship as an engineer at Hawthorn Leslie, the Hebburn shipbuilding and locomotive manufacturer. After his apprenticeship, Bert worked for another seven years on battleships, passenger ships and cargo ships. In 1903, he travelled to Canada as a ‘guarantee engineer’ on the SS ‘Princess Victoria’, which had been bought by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company. The ship was built by Swan Hunter but its engines were supplied by Hawthorn Leslie.

At the time of the 1911 census, Bert was at his family’s terraced home, 22 Warton Terrace, Heaton with his mother, father and three unmarried sisters, Eleanor, Dorothy and Ida. Bert’s occupation was given as a ‘seagoing engineer’. Dorothy, incidentally, recorded on the census form that she worked part time in the Votes for Women Office, Newcastle. (Perhaps she appears in this film.)

Adventurer

Over the next few years, Bert made repeated voyages in his capacity as an engineer, in the Mediterranean and Baltic as well as across the Atlantic and in the Pacific. He worked on the ‘Princess Alice’ (launched in 1911), another Swan Hunter-built ship but this time with engines supplied by Wallsend Slipway and Engineering Co Ltd. It too was bought by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company. And he also served on the ‘Empress of Japan’, built in Barrow in Furness for the Canadian Pacific Steamship Company, a spin-off from the railway company, for which it plied the trans-Pacific route to East Asia.

As a young man, Bert was described as tall, brawny, weathered and ‘sharply angled’. He was used to travelling far from home and it’s perhaps no surprise that when, in spring 1913, aged 35, he found himself in British Columbia looking for his next job, the prospect of a position as second engineer on a voyage to the Arctic appealed to him. Apparently he was offered the position during a chance meeting on a tram.

The leader of the Canadian government-funded expedition was Vilhjalmur Stefansson, an already famous explorer and ethnologist, and the main aim of the mission was to find an undiscovered continent, which some believed to lie under the polar ice cap. Stefansson had assembled the largest scientific staff ever taken on an expedition, ten men from a range of disciplines. In addition, there was to be a crew of twelve under the leadership of Robert Bartlett. Four years earlier, Bartlett had captained the ‘Roosevelt’ from which Admiral Peary had launched an expedition from which he claimed to have reached the North Pole. There would soon also be seven Inuit people, including two young children, eight year old Helen and three year old Mugpi, plus a passenger, Jack Hadley, who, it was said, had more Arctic experience than everyone else combined, dogs to pull the sleds and a ship’s cat.

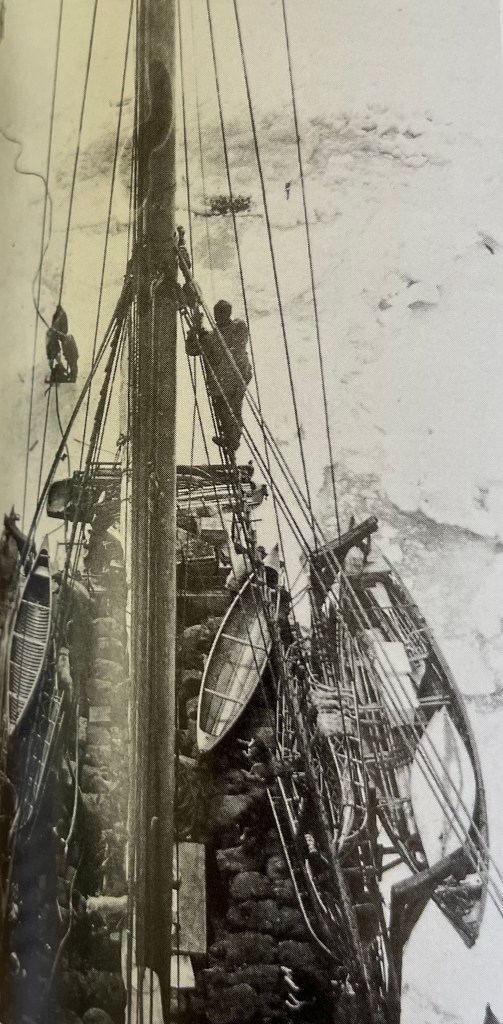

They were all to sail aboard the CGS ‘Karluk’, a 19 year old retired wooden whaling ship, originally built for the Californian fishing industry. It was perhaps an odd choice of vessel on which to take on the inhospitable Arctic.

Before the ship could sail, its engines (one of which was described by the chief engineer, John Munro, as an ‘old coffee pot’) had to be overhauled and many other repairs undertaken. Bert was already a busy man.

There were tensions on board ship from the beginning. Bartlett was unhappy with the suitability of both the ship and its crew, many of whom were very young and few of whom had been anywhere near the Arctic. Within days, he fired the First Officer for incompetence and promoted the inexperienced 22 year old Scotsman, Sandy Anderson.

First Months

The ‘Karluk’ set sail from Esquimalt in British Columbia on 1 June 1913 to a huge fanfare but within days, first of all the steering gear and then the engines stopped working. Bert was even busier. They then hit fog. Despite being midsummer, it was already cold, as low as three degrees Celsius. After anchoring off Nome in Alaska for more repairs and supplies, the ‘Karluk’ passed through the Bering Straits that separate Canada from Russia. On 27 July, it crossed the Arctic Circle (66 degrees 33 minutes north). Conditions quickly deteriorated further. A north-westerly wind battered the ship, which began to take on water in the heavy seas. By 1 August, far earlier than expected, it was snowing heavily and the crew had to steer the ship through free-floating rafts of ice. The first polar bears were sighted, shot and skinned for food and clothing.

But that night, just 25 miles from Port Barrow, Alaska, the ship ground to a halt, trapped in the now frozen ocean. Within a week there was enough of a thaw for the order to be given to push through the ice but it was the start of a pattern. And by the end of the month, the stricken ship was firmly stuck in a mile and a half wide ice floe which itself was slowly drifting westwards, well off the ‘Karluk’’s planned course. It was becoming apparent to everyone that they would be stuck in the ice until the end of winter. All they could do was try to survive.

At this point, somewhat surprisingly Stefansson, the expedition leader, decided to leave the ship along with a hand-picked group of men, the twelve best dogs and a percentage of the supplies, ostensibly to hunt caribous. Opinion is divided as to whether he had ever planned to return.

The rest of the crew, scientists and passengers remained aboard the ‘Karluk’ which slowly drifted until, in late September, the wind-speed increased further and carried the ship, and the ice surrounding it, upwards of 30 miles a day westward into the middle of the Arctic Ocean. There was now no chance of expedition leader Stefansson and his party rejoining the ship. And for the most part, it was too dangerous for those on board to disembark to walk, ski or play games on the ice. It was now -13 Celsius.

In October, they watched, terrified, as huge ice floes, drifting in opposite directions, crashed against each other. Blocks the size of houses were tossed in the air and landed one on top of the other. Everyone on board must have been terrified.

Winter

Bert together with the chief engineer, John Munro and the two firemen, was instructed to take the faulty engine apart and repair it hopefully once and for all. Bert also ran water pipes from the engine room fire to a tank he installed below, giving a much appreciated supply of hot water for washing.

But outside the weather grew ever bleaker and windier, the ship was taking in water, necessitating the crew taking turns on a hand pump. Captain Bartlett ordered many of the ship’s supplies to be loaded onto the ice floe outside for if, or when, anything happened to the ‘Karluk’.

By the end of November, the Karluk had drifted 300 miles westwards and was heading for Wrangel Island, off the coast of Siberia. The inside of the ship was coated in ice and long, jagged icicles hung from the ceilings. Throughout December, the temperatures plummeted to as low as -35 Celsius. The unrelenting wind was from the north and north-east. There was permanent darkness. Bert continued to work flat out on the ship’s engines.

Despite all the hardship, Christmas was celebrated in style. Bert, who had earlier joined in with often forlorn attempts at bringing the crew, scientists and Inuits together by, for example, playing the comb in a scratch orchestra, was one of three men to get up at 5.30am to decorate the ship’s saloon with flags and ribbons and to organise a sports programme on the ice for the whole company. There were races, jumping competitions and a tug of war involving everybody. When it was too cold to continue, they all went back on board for a lavish Christmas dinner planned for from the start of the voyage. It was an important day of team-building but any sense of well-being was short-lived.

Abandon Ship

The following morning, a sound like a gun shot alerted everyone aboard to the fact that the ice, which was now pressed tightly around the side of the vessel, was suddenly cracking. Plans were made for abandoning ship. They were over 50 miles from land.

Over the next few days, the cracking of the ice intensified, as did the wind and also the preparations for leaving the ship. One of Bert’s jobs was to make cooking tins. Then, early in the morning of 10 January, there was a grating sound and the ship shuddered violently. A crack appeared in the ice on the starboard side.The ship started to rise and list. When water began to pour into the engine room, Captain Bartlett gave orders to empty the emergency stores onto the ice and then abandon ship. Two of the Inuit men built a pair of snow houses on the ice, laid boards on the floor and Bert installed a stove in one of them.

Captain Bartlett alone sat on the ship, playing his favourite gramophone records until with water splashing even across the upper deck, he listened to the first notes of Chopin’s ‘Funeral March’, lowered the flag to half mast and finally abandoned ship himself as his men watched the ‘Karluk’ slowly sink. The party was now marooned on an ever-shifting ice pack deep into the Arctic winter. They called their new home at 73 degrees north and 178 degrees west ‘The Shipwreck Camp’. The temperature had dropped to -38 Celsius. Many of the men were weak and suffering from frostbite or injury, some slept all day. Bartlett daren’t try to move the company either to nearby Wrangel Island or more distant Siberia but, against his advice, four men decided to leave the camp straightaway and take their chance on foot across the ice. They were never seen again.

Island

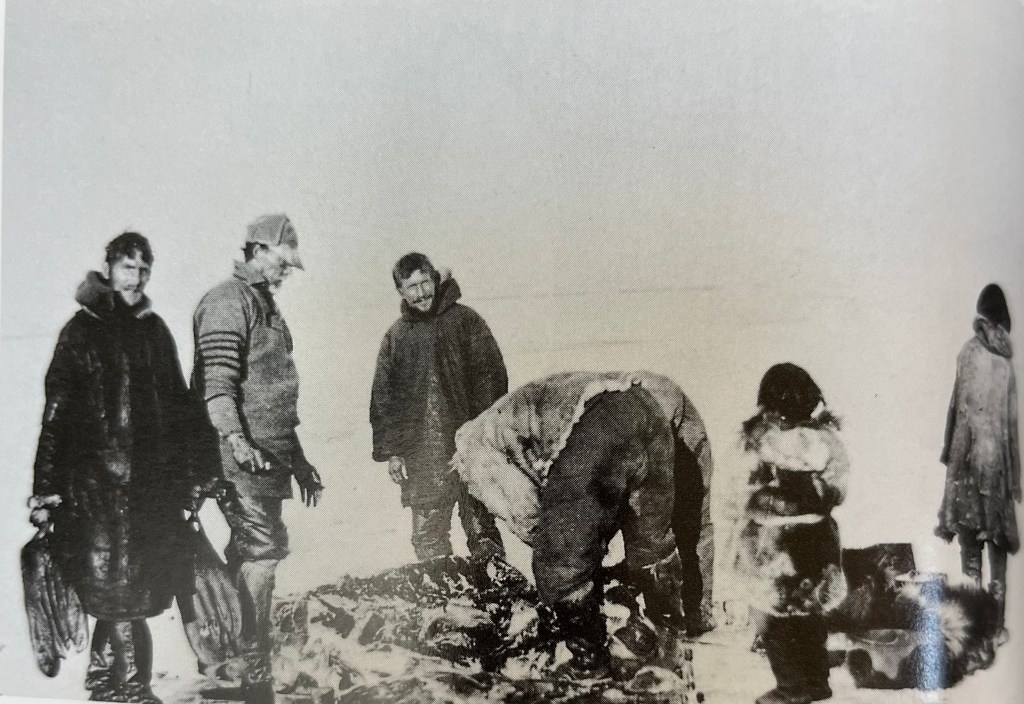

However, in early spring, as soon as most men seemed strong enough and there were enough hours of daylight, Bartlett decided that they had to try to make it to land before more of the sea unfroze. The party quickly discovered how uneven the ice was. There were large ridges and hummocks to negotiate. Sometimes they could walk round them but on other occasions, they had to manoeuvre the dogs and provisions over the top, just one ridge taking hours. Sometimes there were breaks in the ice that they had to find a way across. Every afternoon, they had to build new snow houses in which to spend the night. Their diet was now primarily biscuits and pemmican (a calorie rich mixture of tallow and dried meat). But eventually, after 23 days they made it to the land, the inhospitable but safer, Wrangel Island.

Soon Bartlett decided that he, along with Kakaktovik, one of the Inuits, and seven dogs would try to make it back to the Siberian mainland to summon help, leaving the remaining men on the island to await his return and, hopefully, rescue. Although, the captain had left detailed instructions about how the remaining company was to be divided into groups of three or four and spread around the island to maximise their chances of catching food, tensions that had been bubbling throughout the trip, soon came to the surface. Provisions were now strictly rationed but Bert and one of the men he ‘roomed’ with had been ill, like many others in the party, and were unable to hunt. Consequently, and to the chagrin of some, they used up their supplies more quickly than they should have done and relied upon the kindness of their comrades.

Bert Williamson’s responsibilities extended far beyond engineering. The ship’s doctor had left the camp with Steffanson, the erstwhile expedition leader, and so Bert often took on the role. This extended to his amputating the leg of one young seaman, using a skinning knife and a pair of tin shears. He also cooked sometimes and was credited with accidentally discovering that pemmican tasted much better fried in seal oil. Nevertheless, many of the men could hardly bear to eat it. Sadly, for much of the time, they had no alternative.

Tensions

It was now May and almost a year since the ‘Karluk’ had set sail. The weather was still miserable, with strong winds blowing the snow about but the higher temperatures began to melt the snow houses so they had to revert to tents. Everyone was under great physical and mental strain. More and more of the men, Bert among them, were weak and suffering from swollen limbs. He could no longer walk and had to be pulled on a sled when there was a need to move the camp to try to find somewhere with a better food supply. This must have been harrowing for him as sometimes he had to be left unattended and the ice was now melting fast. When he tried to walk, his legs buckled. And still there were disputes about rations.

On the evening of 12 June, Bert was distressed. He complained that he couldn’t breathe and that his heart was failing. Not all of the party were as sympathetic as he might have hoped. Some accused him of suffering from indigestion after over-indulging on freshly caught gull. The men in his billet were also accused of stealing birds from another tent. Relationships were at an all-time low.

The culmination came on 25 June when gunshots were heard and George Breddy, one of the ship’s firemen, a man in his early twenties, was found with a gun by his side. Bert and his other roommate said they had been asleep at the time. Although at first, there was a debate only about whether Breddy had fired the shotgun by accident or with the intention of killing himself, soon some of the party suspected murder, based on the position of the weapon, and believed Bert Williamson was the murderer. The truth would never be known.

Soon it was July. It was windy, pouring with rain and the temperature hovered just below freezing point. Bert installed a stove made out of an old coal oil tin in his tent. The crew and the Inuits spent the evenings gathered around it drinking tea. But they had all but run out of food and had taken to staying in bed all morning to conserve energy or because they were too weak to get up. On 20 July, they resorted to collecting as many bird wings as they could find lying on the ground. The Inuits showed the men how to pluck the feathers from them and make a kind of soup from the bones. But, luckily, at that point of desperation, one of the Inuits managed to shoot and retrieve a walrus. It gave them some respite but by the 24th, they were eating only the hide, boiled. The ice was now crashing in the bay. There was absolute despondency.

Trek

In mid August, Bert Williamson decided to walk 30 miles to check on the other group of men, who were stationed in a place they called ‘Rodger’s Harbour’. He wasn’t known to be an enthusiastic walker, even when fit and well and the rest of the party didn’t think he was capable of making the journey. Nevertheless, on 19 August, he arrived only to find all the men there in very poor condition. He later said they refused his offer of food and so, taking back with him a gun and a supply of their unused tea, he set off on the return journey just 12 hours after his arrival. Predictably, lack of food together with his generally poor health began to take its toll. Heavy snow began to fall, blotting out the landmarks he’d used to guide him on the outward journey. He was lost and weak and began to hear voices that he knew weren’t there and then another noise, the call of what he believed to be an owl. Whether it was real or not, he said he followed the sound into a ravine and onto what he eventually found to be the path back to camp. He later said that without that invisible owl, he would have perished that day.

But death seemed to be closing in anyway. The stranded explorers were now subsisting mainly on rotten flippers, watery blood soup and a few roots identified by the Inuits as edible.

They had to take ever more drastic measures to survive as another Arctic winter loomed. Bert and another crew member opened the grave of the unfortunate George Breddy and removed the blanket and boots in which he’d been buried. They couldn’t afford to waste them on a dead body. Every day, someone was tasked with scouring the horizon in the hope of spotting a ship in what they knew was a narrow window of hope. August gave way to September.

Rescue mission

Meanwhile, Captain Bartlett had eventually reached Siberia and raised the alarm. Even then, he had to spend a month in Nome, Alaska waiting for conditions that would permit a rescue boat to reach Wrangel Island. But eventually on 13 July, four months after he had left the camp, a cutter, the ‘Bear’ set sail with Bartlett on board. To his frustration, the ship made various stops on its way north. It had to drop off supplies for local schools, take passengers along the Alaskan coast and at Emma Town, they even picked up Lord William Percy, a distinguished ornithologist and a son of the Duke of Northumberland. The ‘Bear’ had to do its regular work. It also needed the ice conditions to improve.

On 21 August, the ‘Bear’ left Point Barrow and embarked upon the final leg of the journey to Wrangel Island. In the meantime, the Russian government, at the request of the Canadians, had also sent two icebreakers, the ‘Taimyr’ and the ‘Vaigatch’ to the island. At last, help was close at hand.

However, with the ‘Bear’ now only 20 miles from the island, it became enveloped in fog which made navigation impossible and when that finally lifted, strong winds blew the ship back towards the Siberian shore. The captain then announced that the ship would have to return to Nome for more coal. Meanwhile, on Wrangel Island, hope was all but gone.

Back on dry land, Captain Bartlett desperately enquired as to the progress of the Russian icebreakers only to discover that they had got to within 10 miles of Wrangel only to hear, on 4 August 1914, that Russia was at war and they were to head south to Anadyr to serve their country.

Bartlett immediately persuaded the owners of two other small ships to let their vessels, the ‘King and Winge’ and the ‘Corbin’, join the search. The ‘Bear’ too set off again once it had taken coal and other supplies on board but on 7 September, it struck ice. The ‘King and Winge’ was faring only marginally better but it was, at least, now within sight of the island. As the schooner got closer, the crew blew whistles and fired rockets. They had spotted a tent out of which a man crawled.

The following day, as the ‘King and Winge’ with all the survivors on board, was heading back to Alaska, they met the oncoming ‘Bear’. Captain Bartlett was reunited with the other survivors. In total, 11 men had died. Twelve people were rescued. Bartlett and Kakaktovik had previously made it to safety along with Stefansson and his party who had left the ship the year before.

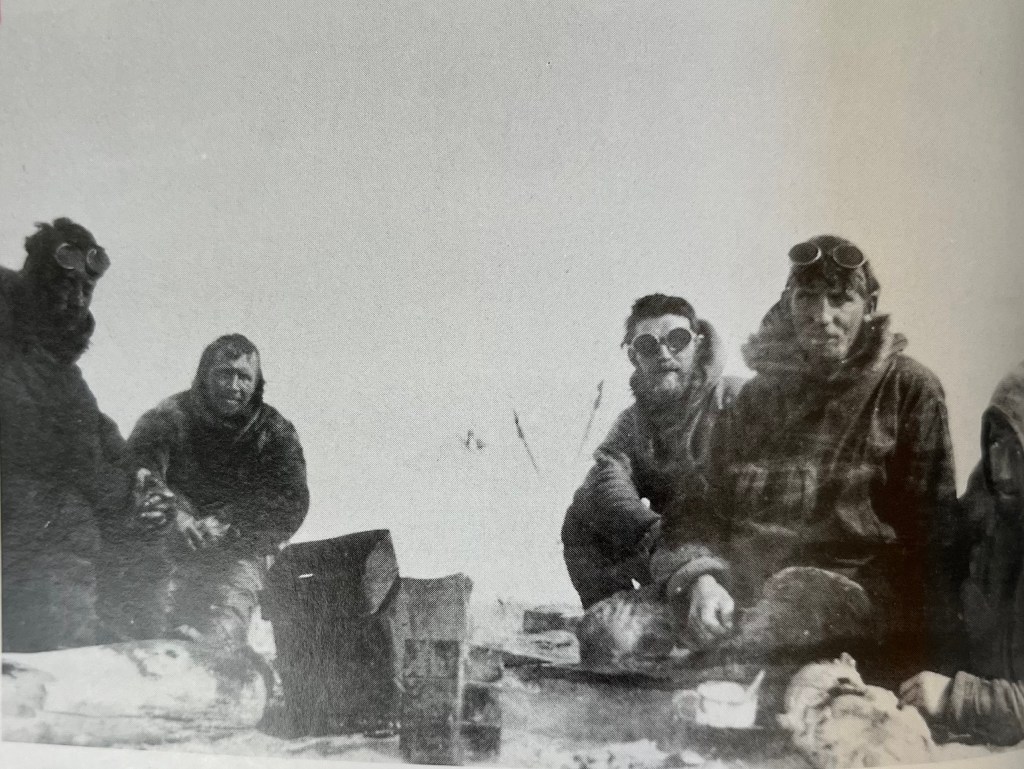

The photograph below, taken on the ‘Bear’ shows Bartlett along with all of those rescued after a wash, change of clothes, shave and several slap-up meals. Bert Williamson is third from the left with no cap and with his hands in his pockets.

Home

News of the rescue was carried in papers across the world. And on 5 December, having been reunited with his family in Heaton, Bert Williamson, now of 145 Addycombe Terrace, was interviewed by a reporter from the ‘Newcastle Daily Chronicle‘, which is how his remarkable story came to our attention 110 years later.

His father had died while Bert was away and so the family had moved to a more modest property, a Tyneside flat. It would have been an emotional time and there would have been so much catching up to do but there was a war on and so it wasn’t long before Bert was back at sea. He served in the Royal Navy from 1915 aboard HMS ‘Woodnut’ and HMS ‘Sunhill’ before returning to Canada in 1919. There, he spent the rest of his career on the HMCS ‘Malaspin’, a coastal patrol vessel, before volunteering his services again in WW2.

On census night 1921, Bert’s mother, Eleanor, and two of his sisters, Eleanor and Dorothy were still at 145 Addycombe Terrace. But by 1939, they had all moved to South Elkington near Louth in Lincolnshire not far from Skegness where Bert’s other sister, Ida was working as a housekeeper. Eleanor senior was now 90 years old.

Although many of those involved published diaries or accounts of the ill-fated expedition, Bert rarely spoke publicly about his traumatic time in the Arctic, although decades later, he did give one interview to Canadian radio, a copy of which is held in the Canadian National Archive in Ottawa. We haven’t yet managed to listen to it yet but if you happen to be passing…! He had married Florence Liette MacKay in 1922 and settled on Vancouver Island, British Columbia. The couple had a daughter, Geraldine.

Robert Williamson died on 9 February 1975 in Victoria, British Columbia, aged 96. His obituary writer, Jim Lotz, a Liverpool-born writer, researcher and teacher, who settled in Canada and knew him in later life, wrote of him:

‘He was a small man, but tremendously tough. To the end of his days he remained alert and cheerful, and was a great favourite with the local children on his walks around the block.’

He was also another Heatonian with a remarkable story to tell.

Acknowledgements Researched and written by Chris Jackson, Heaton History Group. Most of what we have gleaned about Bert Williamson’s experiences in the Arctic came from the contemporary diaries and later writings of other survivors of the ‘Karluk’. Many of these were brought together in Jennifer Niven’s book ‘The Ice Master’ (see below), which is well worth a read. The article here concentrates on Bert but the book and the first-hand accounts on which it is based gives so much more information about the experiences of all the other members of the expedition.

Sources

‘The Ice Master’ / by Jennifer Niven; Hyperion, 2000

‘The Last Voyage of the Karluk: flagship of Vilhjalmar Stefansson’s Canadian Arctic Expedition…, as related by her Master, Robert A Bartlett’ / Ralph T Hale, McClelland, Goodchild and Stewart, 1916

‘Obituary: Bert Williamson’ / Jim Lotz in ‘Polar Record’ Vol 17 no 11, 1975 p708-9.

‘An Unknown Region: Perils of the Stefansson Expedition – a Newcastle man’s story’ / The ‘Newcastle Daily Chronicle’; Tuesday 8 December 1914

‘Williamson, R J – interview / Those Were the Days series; Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 28-04-1971 (not yet heard)

There was also a BBC Scotland documentary ‘Karluk: surviving the Arctic’ first broadcast in 2007 but not currently available on iPlayer. A number of podcasts and short films are also available.