On 19 June 1921, census night, two young boys of a similar age were living just across the railway from each other in Heaton. Charles Flinn was 13 and Thomas Dennis 11.

Charles

Thirteen year old Charles Flinn was at 16 Guildford Place with his mother, Frances; father, James; two older sisters, Hilda (26) and Grace (23); and two older brothers, Alfred (16) and Archibald (15). Apart from the two younger boys, Charles and Archibald, who were still at school, and their mother, everybody in the household had skilled jobs.

James was a fitter at Parsons Marine Turbine Works in Wallsend, where he later spoke of his involvement in the time trials of the ‘Turbinia’ on the River Tyne; Hilda was a shorthand typist in North East Railway’s goods office; Grace had been a tracer at Swan Hunter and Wigham Richardson in Walker (although, like many others on Tyneside, and particularly women who’d had to give up their jobs to returning servicemen, she was now out of work); and Alfred was studying part time while working for North Eastern Marine Engine Company, so most likely serving an apprenticeship. Frances’s brother, also called Alfred, a garage proprietor, was also living with the family. Charles’ later recalled his first job on leaving school at his uncle’s garage. He remembered serving petrol in tins, before the existence of petrol pumps.

We know from previous censuses that Charles had other older siblings, Sarah Isabel (Daisy), Wilhelmina (Minnie), Margie and John. In 1911 Minnie had been an apprentice tracer like Grace later. Although James had been born at Bigges Main and Frances at Curragh Camp in County Kildare, Ireland, and the couple had lived in Byker when they were first married, they had lived in Heaton for over ten years including at 96 Tosson Terrace and at 43 Warton Terrace. Although, it must have been a bit of a squash with eight people living in the terraced house on Guildford Place, it was more spacious than their previous homes and there were three wage packets and Alfred’s business to support them. The family were by no means wealthy but they had been gradually bettering themselves and seemed to have a relatively secure future.

Thomas

Meanwhile at 55 Denmark Street, eleven and a half year old Thomas Dennis (born 13 November 1909) was at home with his father, also called Thomas, who had most recently worked as a sawyer at a pit in Wallsend but was now out of work; older sisters, Mary (29) who stayed at home to ‘run the house’, and Florrie (15) who worked as a tailoress at H Freeman and Son, a shop at 12 Shields Road West. Older married sister, Lily (28), her husband, Gilbert (a labourer) and their three young children, nine year old Bella, Gilbert (almost two) and Evelyn (nine months) completed the household.

Previous censuses and other records, shows that there were older sisters: Elizabeth (born 1885), Annie (1886), Beatrice (1888), Evalina (c1898) Isabel (c1899), Edith (1901) and that, by 1911, Thomas senior was already a widower. It’s recorded on the census form that he had eight children still living and that two had died. We know from the family that his wife, Isabel, had died in childbirth.

Thomas senior had been born in Leeds and, having enlisted in the Kings Own Scottish Borderers, an infantry regiment, aged 20, he was eventually posted to Berwick upon Tweed. The older children in the family were born there. Thomas and his wife came to Newcastle after he had served for 20 years. Before moving to Heaton, they lived in Byker and Walker.

So in 1921, Thomas, who would barely have remembered his mother, was growing up in a household where his father was out of work and the only income, in addition to that of his brother in law – who on a labourer’s wage, had to support a wife and three children – was that of his 15 year old sister. Life must have sometimes felt tough.

Housing

Despite being so close to each other and the household sizes being similar, the housing conditions in Guildford Place and Denmark Street would have been quite different. 16 Guildford Place had nine rooms ‘excluding scullery, landing, lobby, closet and bathroom’ so, assuming there were five bedrooms, enough space for the eight inhabitants with the two older sons of the family and the two daughters sharing bedrooms. This would have left a kitchen and two downstairs living rooms. The Flinns’ neighbours included a mechanical engineer, a marine engineer, school teachers, clerks, a labour secretary, a circuit manager, a stationer and a medical student. The vast majority were white-collar workers. Nevertheless, a number, like Grace, were unemployed. A number of the houses, including number 16, were destroyed during WW2. There is now post-war block of flats on the site.

55 Denmark Street is also long demolished. It may well have been a Tyneside flat like those illustrated below and like many properties in Newcastle built from the 1870s onwards.

We know from the census form that it had four rooms (fewer than half the number in Guildford Place) ‘excluding scullery, landing, lobby, closet and bathroom.’ Nine people would have lived and slept cheek by jowl, with several people sleeping in each of three bedrooms, leaving one room to have doubled up as a kitchen and living space but somebody may well have slept there too. The overcrowded conditions may have contributed to the death in 1909 from influenza at 55 Denmark Street of Thomas’s cousin.

Neighbours included labourers, fitters, a turner, a pattern maker, a coal cutter machine man, a rivet heater, a tobacco spinner, a crane driver, a cabinet maker, a glass bottle blower, a bottle packer, a gramophone, cycle and pram dealer and a civil service manager. The majority were blue-collar workers, many were in skilled occupations. There were certainly far worse places to live, even within walking distance, but noticeably more residents reported being out of work than on Guildford Place.

School

We have no way of knowing whether the boys knew each other. They lived only a couple of hundred yards apart, albeit separated by the railway line, but they attended different schools. Charles went to Chillingham Road, which he apparently hated, having a particular aversion to the headmaster, Mr Gillespie, who is described in Jack Common’s ‘Kiddar’s Luck‘:

‘Mr Gillespie was popular with the boys…. but in his anger he could be a pretty terrible figure. Experts testified that he could put more sting into a lashing than any other teacher in the town…’

Sixty odd years later, Charles revisited the school and was amazed by how ‘light’ the interior was – he remembered it as a dark, forbidding place.

Thomas went to North View School. We don’t know much about his time there or his impressions. We do know that North View was closed for a time in 1919 due to the influenza pandemic which had claimed a life in his extended family. We don’t know whether Thomas and his family were affected beyond that but given what we have pieced together about his home life, it is perhaps unsurprising that Thomas wasn’t an academic ‘high-flier’.

But very soon, both boys’ lives underwent huge change.

Sunshine

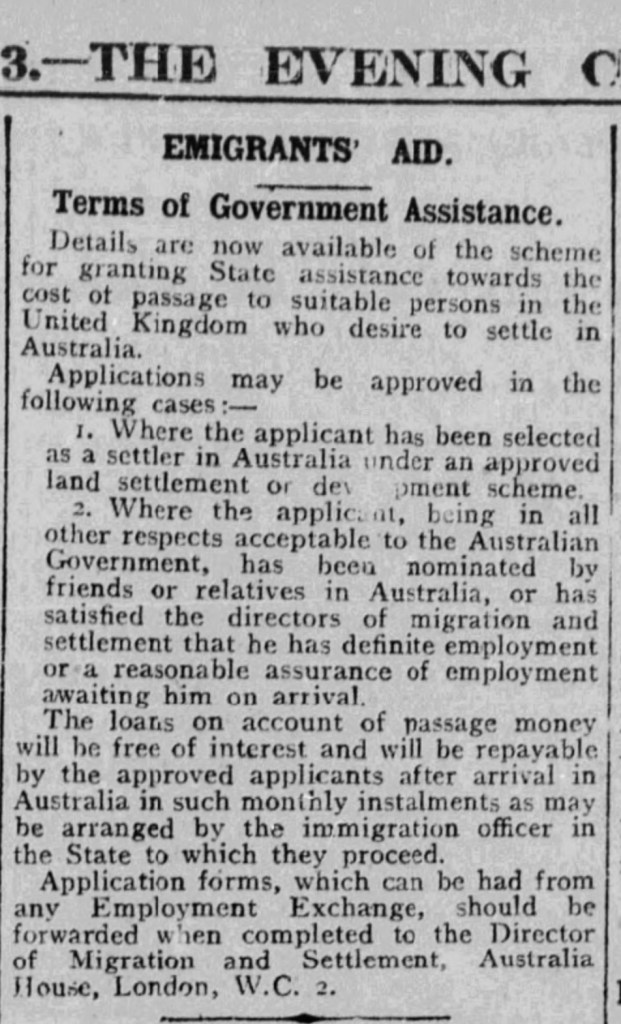

In 1922, the Australian government introduced an assisted passage scheme to replace an earlier one aimed only at ex-serviceman. Perhaps because of a worsening economic situation here, caused in part by those who had completed military service needing to return to civilian jobs and also the reduced demand for ships and armaments, which particularly affected Tyneside, the British government had lent Australia £3,000,000 to encourage Britons to emigrate there. In June and July, advertisements for the scheme were printed in local newspapers.

On 11 November 1922, James Flinn, Charles’ father, set sail from the Port of London on board the ‘Ormuz’. His stated destination was Melbourne. Charles clearly remembered the poverty of that time, recalling that he saw very poor people rummaging through rubbish in the hope of finding pieces of coal. And the Flinn family were affected personally. Charles recalled strikes and lock-outs and his father having only 2-3 days work a week. He overheard arguments about money between his father and his uncle. He said too that on one occasion he was sent to the butcher’s with a postage stamp to buy a single chop.

It’s easy to see the attraction of making a new life in Australia where work was said to be plentiful. But James set sail alone, perhaps to see if it was a good move before subjecting the rest of the family to upheaval and expense or to allow him to earn the money that would be needed for them all to follow.

We know from his grandson, Peter, that James quickly found a good job with the famous Sunshine Harvester Works which made agricultural machinery and was at that time the largest factory in Australia.

Moreover, H V McKay, its owner, built housing and many other facilities for his workers and their families, along the lines of a ‘garden city’.

Not surprisingly, James’ move was considered a big success. Daisy and Grace duly followed in 1923 and, in 1924, young Charles, now 16, his mother, older sisters Hilda, Minnie, Margie and brothers Alfred and Archibald also headed to the Port of London and boarded ‘The Sophocles’ bound for Albany, Western Australia. Charles had spent all his life in Heaton. He later spoke of his love of Jesmond Dene, as well as Newcastle United, St Mary’s Lighthouse and Geordie songs. But a new life awaited him.

The Flinns’ ultimate stated destination was 46 Forrest Street, Sunshine, Melbourne, a 35 hour drive away even now. This house, one of several that McKay had built for his senior staff, became the Flinn family home. However, in 1929 while at work, James, Charles’ father, suddenly had a heart attack and died, aged 65. A couple of years later, Frances, Charles’ mother, moved to the other side of Melbourne with Charles and four of his sisters.

Charles worked as a fitter, like his father had done at Parsons, and in 1937 married Jean Mary Ely, the daughter of an orchardist from Harcourt in central Victoria. Jean and Charles had a son, Peter, and three grandchildren.

The same year that Charles married, Charles’ mother and all his sisters except Daisy, who was married and settled in Australia, returned to England try to get treatment in London for Grace who suffered from multiple sclerosis. Grace died in London in 1943 and Frances the following year. However, the remaining sisters returned to Australia after the war and stayed there for the rest of their lives.

Brother Archie merits an article, if not a book, all of his own. Suffice for now to say that he returned to England as early as 1927 and his family never heard from him again. Eventually, however, Peter, managed to find out more. He had joined the army and during WW2 was assigned to the Special Operations Executive (SOE), which conducted espionage, sabotage and reconnaissance as well as aid local resistance movements. He rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and was awarded both the MBE and OBE before dying in somewhat mysterious circumstances in 1952, aged 46.

Charles’ other brother, Alfred, married and remained in Australia all his life.

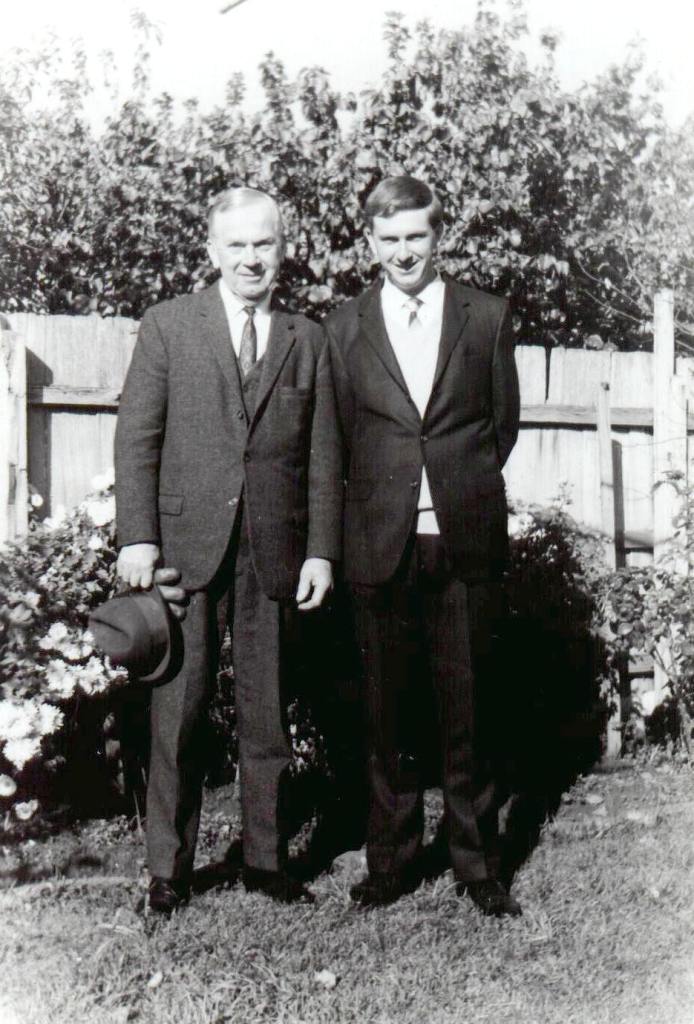

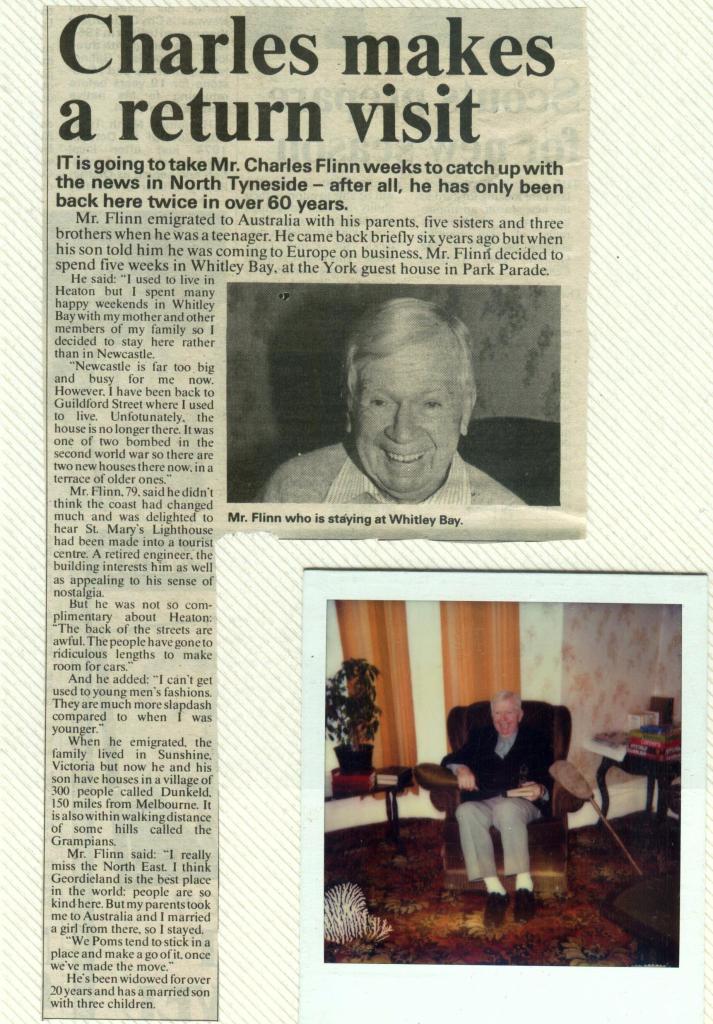

Charles too settled down under but always considered himself a Geordie. He returned to the north-east with Peter in 1981, which is when he revisited Chillingham Road School. They also visited a friend Charles had not seen for 57 years. His son said that he sat spellbound as the pair sang ‘Blaydon Races’ together, his father remembering every word. Charles became something of a local celebrity during his visit:

Sugar

Just as the Flinns were settling into their new life and embracing the opportunities it afforded them, back in Heaton the Dennis family’s world fell apart. Young Thomas’s father died on 8 December 1925. He left effects to the value of £38. Thomas was just 16 and, the only boy with nine older sisters, he was suddenly expected to fend for himself. We don’t know what happened in the immediate aftermath of Thomas Dennis Senior’s death but the economic situation hadn’t improved. In April 1925, Winston Churchill had announced a return to the ‘Gold Standard‘, restoring the pound to its pre-WW1 level. This policy decision, which made British exports more expensive, is thought by many to have led to higher unemployment, increased poverty, the 1926 General Strike and ultimately the ‘Great Depression’.

It has been handed down through the family that Thomas spent some time in a workhouse, although his granddaughter, Sarah, was unable to find a record of him being in Newcastle Workhouse. She did find a record of a Catherine Dennis, who she believes to be Thomas’s stepmother, receiving some financial assistance.

We do know that Thomas eventually made his way to London and on 28 January 1928, two years after his father’s death, he boarded the ‘Ormonde’ bound for Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. He gave his address as 55 Denmark Street, Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne and his occupation as ‘miner’.

There were people from all over the country and from all walks of life on the ship, some travelling alone and many with family members and they were heading to destinations all around Australia. What is interesting about Thomas’s entry is that his is the sixth name in a list of thirteen young men, all from the north-east and all between the ages of 14 and 18. The youngest was 14 year old W E Blevins of Wallsend, described as a ‘farm learner’ and the oldest, along with Thomas, M Bennett of Camperdown Street, Newcastle ‘a motor driver’. All of them were heading for Brisbane.

Youth Migrant

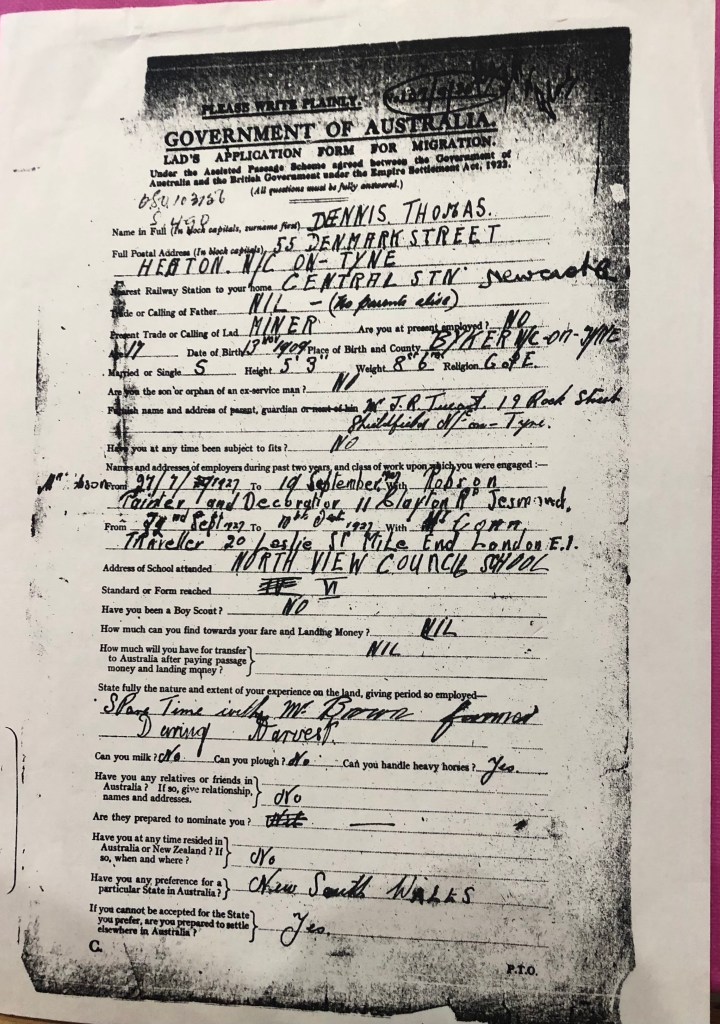

Thomas and his companions were on a different ‘assisted passage’ scheme from that of which Charles Flinn’s dad took advantage.

The above image shows Thomas’s ‘lad’s application form for migration’ to Australia under the Empire Settlement Act of 1923. The form gives 55 Denmark Street as Thomas’s address even though he’d been in London for a couple of months. His height is recorded as 5 feet 3 inches and weight 8 stone 6 pounds. It confirms that he has ‘no parents alive’ and could find ‘nil’ towards his fare and landing money. Although he gave his occupation as ‘miner’, his last job in Newcastle was for a Mr Robson, painter and decorator of Clayton Road in Jesmond.

Thomas had then moved to London where he says he worked for Mr Conn, a ‘traveller’ (ie travelling salesman) of Mile End. Asked whether he had any experience on the land, he said he’d worked for Mr Brown, a farmer, during harvest and that he could handle heavy horses. His preferred state in Australia was New South Wales. The ‘parent, guardian or next of kin’ who signed his application was Mr J R (John Robinson) Tueart of Rock Street, Shieldfield, who was his sister Isabella’s husband. (So Thomas was distantly related by marriage to the family of footballer Dennis Tueart. Isabella’s husband was the brother of Dennis’s grandfather).

The next form (below) was completed a short time later when Thomas’s application had been approved, confirming that he would be aboard the S S ‘Ormonde‘ due to sail from Tilbury to Queensland (not his preferred New South Wales) on 21 January 1928. By now, Thomas was 19 – and he seems to have grown an inch in height!

In Thomas’s case, as with others, he had to work on a specific farm for at least three years. The migration scheme for young people aged 15 to 18 was devised to help satisfy Australia’s need for rural labour. It was encouraged by the British government, particularly during the 1920s, as a mitigation of high unemployment and poverty, and it was facilitated by organisations such as the Boy Scouts, the YMCA, Barnardo’s and Fairbridge. The Big Brother Movement, an Australian organisation founded in 1925, played a major role. The youth migration scheme, in which the young men (and it was only males at this time), at least in theory, made their own decision to emigrate operated alongside the even more controversial child migration scheme in which children in orphanages, for example, were sent abroad. (The last child migrants were sent by Barnardo’s as late as 1967 and the final youth migrants were sponsored by the Big Brother Movement in 1983.) Nevertheless, the bonding of youth migrants to a particular employer frequently led to exploitation.

Sugar

Thomas was required to spend three three years working on a farm in Bundaberg, an area of Queensland in which many sugar cane plantations are situated. (Perhaps the authorities didn’t believe the slight boy from urban Newcastle really could handle heavy horses.) It is an area which until the early 20th century relied for much of its labour on ‘blackbirding’, the use of (often forced) indentured labourers from the Pacific, a practice often considered a form of slavery. You can see how the use of youth and possibly child migrants from the UK and elsewhere would fill gaps in the labour force which would have resulted from the outlawing of this practice in Queensland in 1908. This legislation saw the beginning of a larger ‘White Australia policy’ as part of which thousands of South Sea Islanders were deported.

Thomas went on to work on the railways and then on further farms in the area. He witnessed many cases of what he saw as injustice and exploitation and went on to become a union official. He worked for 22 years for the Australian Workers’ Union, a job which enabled him to make a difference to the conditions of workers like his younger self. He rose through the union ranks and his family recall that he became friendly with Gough Whitlam, Prime Minister of Australia in the 1970s. Not bad for a penniless orphan from Heaton. But Thomas rarely, if ever, talked about his early life in Newcastle and certainly didn’t retain his accent or entertain the family with Geordie songs. Some of his childhood memories and having had to leave his family may have been too painful.

The photograph below shows Thomas on a sugar cane farm in his union capacity. Incidentally, there is now once again considerable controversy surrounding the working conditions of Pacific Islanders employed as seasonal workers in the Queensland agricultural sector.

Thomas is on the extreme left of this family photograph.

And here he is with two of his grandchildren. The younger girl on the left is Sarah-Mace Dennis, an artist who came to Newcastle this year to find out more about her grandfather’s life here as part of an Arts Council-funded study project.

Thomas Edward Dennis died on 16 January 1992 and Charles Arthur Flinn on 31 October the same year.

The fact that a century after they left Heaton, descendants of both boys, Charles Flinn’s son, Peter, and Thomas Dennis’s granddaughter, Sarah-Mace, decided to return at exactly the same time to find out more about their origins, is both a remarkable coincidence and has enabled us all to know more about the lives of two boys, young neighbours who left, albeit in somewhat different circumstances, in search of a better life.

Acknowledgements

Researched and written by Chris Jackson of Heaton History Group. A very special thank you to Sarah-Mace Dennis and Peter Flinn for contacting us and for sharing information about their Heaton ancestry.

Can You Help?

If you know more about Thomas Dennis or Charles Flinn or have memories or photos to share, we’d love to hear from you. You can contact us either through this website by clicking on small speech bubble immediately below the article title or by emailing chris.jackson@heatonhistorygroup.org

Sources

Ancestry

British Newspaper Archive

‘Child and Youth Migration in the 20th Century‘ / Museums of History New South Wales

‘Kiddar’s Luck’ / by Jack Common; Frank Graham, 1975

Personal recollections of the Dennis and Flinn families (via Sarah-Mace Dennis and Peter Flinn)

Other online sources

(First published in June 2025)