This is the story of a Victorian house. Specifically, a terraced house in Stannington Avenue, Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne. But perhaps more importantly, it is also a story of the lives of the individuals and families who lived there, from when it was constructed to the recent past.

The house, part of a new terrace built in 1890, was constructed at a time that, just over a century later, we find remote already. Britain in the 19th century was the foremost global power. It dominated worldwide trade, which drove, as well as resulted from, the industrial revolution, an economic earthquake powered by steam since the mid-1700s.

Britons saw themselves as the worthy rulers of a great empire, with a ruler, Queen Victoria, who seemed to have been on the throne for ever. Her Golden Jubilee in 1887 was celebrated across the country – in Newcastle alone, some two million people visited the Jubilee exhibition on an area of the Town Moor that came to be known as ‘Exhibition Park’.

International trade and the industrial revolution was also changing society. Newcastle was not just about coal and steel. Rising wealth among the middle classes brought more disposable income, the means to improve living standards. It also brought the means to afford imported luxuries such as wine, cigars and exotic fruits, and the emergence of a range of new merchants to supply them.

But the good burghers of the time were also concerned about their workers. Too much money was being spent on drink, they believed, with families in penury from husbands incapable of restraining their sociable impulses. The Temperance movement was an attempt by churches and society to counter that influence, with the support of industrial barons concerned about loss of productivity (John Wesley had claimed as early as 1743 that ‘buying, selling, and drinking of liquor, unless absolutely necessary, were evils to be avoided’. The rising number of cocoa rooms in cities across the UK was a direct result of that movement.

This was some of the background to Victorian society in the late 1800s. But what of the house itself, and its place in a changing industrial city?

Expansion Eastwards

Worldwide trade and the huge changes in industry had brought about an unprecedented growth in the UK population. Workers were in demand for the new processes and new factories, as well as for the coal mines that fuelled them. Labour in the new industries may have been dirty and unpleasant, but it generally paid better than in agriculture.

The north-east and its ports and rivers were in the forefront of that growth. On the River Tyne, factories and port facilities were expanding eastwards along the north bank of the river into Byker and Wallsend. And housing along with them. Byker already had a population by 1810 of over 3,000. Yet more housing was needed.

Heaton township in 1801 was almost all farmland, with just 183 inhabitants. According to one source Heaton, with just eight farms, comprised ‘about 924 acres of good arable, meadow, and pasture, interspersed with tracts of sand and peat-moss’.

Inevitably, demand for housing drove incorporation of the townships of Byker and Heaton into the city of Newcastle in 1835. And as the population grew, especially in the latter half of the 19th century, development began to spread northwards along Heaton Road from its southern end in Byker. The total number of houses in Heaton grew from 331 homes in 1881 to 2,742 in 1901 (‘Vision of Britain – Heaton’).

Part of the attraction was countryside. People wanted a home that escaped the dirt and poor air of Victorian industry, driven as it was by coal and steam. Soot was a serious issue – coal not only powered industrial processes but also heated every single home. The earliest photos of Newcastle show a city that was predominantly black in colour – coated with layers of soot.

There was also serious poverty. The inner-city rows of smaller ‘two-up and two-down’ terraces contained houses shared by multiple families. They lacked running water – people shared a standpipe in the street, the privy was outdoors, and both sewage and rubbish were frequently thrown out of doors and windows. These areas were vectors for disease.

Unsurprisingly, the Victorian middle-classes wanted homes away from such crowded inner-city districts. Demand grew for the fresher air of the outer suburbs. Smart terraces were built on the outskirts of town, and semi-detached or detached villas appeared in prime areas. Heaton Road must have been considered such a prime area, witness the prevalence of large semis and detached houses both north and south of the railway line.

South Heaton grew rapidly during the housing booms of the late 1860s and 1870s, then again at the end of the century. Heaton had a population of 257 people in 1871, but by 1901 the number had soared to 22,913. Richer, middle-class families could live in larger houses with running water, coal fires in every room, scheduled rubbish collections and rooms (usually a cold and stuffy attic) for servants to carry out the day-to-day work of the house.

Yet despite the greater wealth of this nouveau riche, most people still rented their homes. A house was not considered a capital asset, except among the few who were prepared to speculate and risk losing their shirts. For most people it was but a shelter, a place of light and warmth, somewhere to take refuge from the northern winter.

Private landlords varied from the original landowner to the builder/developer, as well as private investors. A house that might cost £500 to buy could be rented for around £50 per annum. Such a home could have seven or eight rooms, enough for all the family plus one or two servants.

All Modern Conveniences

This then was the context for the lines of new terraces spreading northwards along Heaton Road in the late 1800s. One such terrace was Stannington Avenue, built in 1889-1890, then the northern-most terrace in an expanding South Heaton. The street was probably considered fairly grand – the houses were quite large for terraces and looked onto the grounds of Heaton Hall, still the home of the Potter family, an offshoot of the Ridleys.

From this point northwards on the west side, housing development ceased. This side of Heaton Road was the Heaton Hall estate (now Heaton Park) and remained so until the 1930s. Residents in the street could look forward to enjoying their leafy outlook for years to come.

The name of the street almost certainly comes from association with the Ridley family – the village of Stannington neighbours the Ridley estate of Blagdon Hall. And Heaton’s oldest football team, Heaton Stannington FC, also takes its name from the street – the club was founded shortly after Stannington Avenue was constructed, and many of its early players came from the streets around. Players in 1903 included JJ Ryan, T Robson, G Nicholson, C Hall, J Ritchie, J Meanell, J Stoker, A Bennett, W Tovey, T Skelton, A Readhead, H Jackson, H Jordan, R Shipley, R G Perring, F Stevens, J Hall, A V Armstrong, W Jordan, J Main and R Robson (source: Heaton Stannington FC).

Individual houses in the terrace were probably sold or rented out as they were completed. Ward’s Directory of Newcastle lists no street named Stannington Avenue in 1889-1890 – presumably it was still under construction. House numbering began at the east end, Heaton Road, this being the main north-south thoroughfare. The 1889-1890 Electoral Register shows only no 4 occupied, by one William Thompson, gentleman. One year later, Ward’s 1890 shows residents’ names for 1-7, as if homes in the western half of terrace from no 8 onwards were not yet completed.

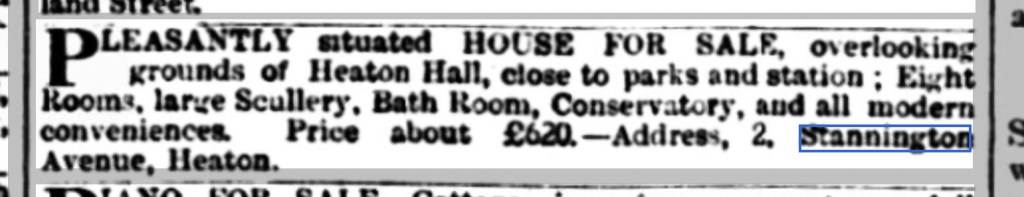

Advertising at the time made the most of the location. One the first houses in the terrace to be completed, no 2, was a few years later promoted as: ‘Pleasantly situated House for Sale, overlooking grounds of Heaton Hall, close to parks and station; eight rooms, large Scullery, Bath Room, Conservatory, and all modern conveniences. Price about £620.’

So who would choose to live in one of these ‘desirable’ new homes? For that we’ll have to move on to Part 2. To be continued ….

Acknowledgements

Researched and written by Philip Hunt of Heaton History Group. Philip used publicly available sources and archives would ALSO like to thank members of Heaton History Group for their help.

Can You Help?

If you know more about Stannington Avenue or have memories or photos to share, we’d love to hear from you. You can contact us either through this website by clicking on small speech bubble immediately below the article title or by emailing chris.jackson@heatonhistorygroup.org

First published by Heaton History Group on 18 November 2025.

I lived at number 5 as a child from 1938 until 1959. I still remember the names of the people from number 1 to number 7. At that time the front lower room had an ornamental railing around the top of the bow window, and each house had a dormer window in the larger attic room and a skylight in the smaller one (bedrooms for the servants?). Separate toilet next to the bathroom and even a toilet in the backyard, again for the servants? The glass conservatory was still in existence where my father bred budgerigars! The iron railings surrounding the front garden as well as the iron gate were removed during the war for the war effort! Please contact if you have questions.

Lovely to hear about your memories of the street. It’s interesting to hear that the front room had a railing above it, I suppose to match the railing (for a small terrace in front of french windows) above the front door – that smaller railing is still there on most of the houses. The dormer windows and skylights in the roofs are also still there, unfortunately they are not shown in the image – I couldn’t get them included by the software. On the separate drainage in the backyard, I did notice this and wondered if there could have been an outside toilet at one time. Most of these houses have changed a lot at the back from when they were constructed, especially with kitchen extensions, and now each one is individual.