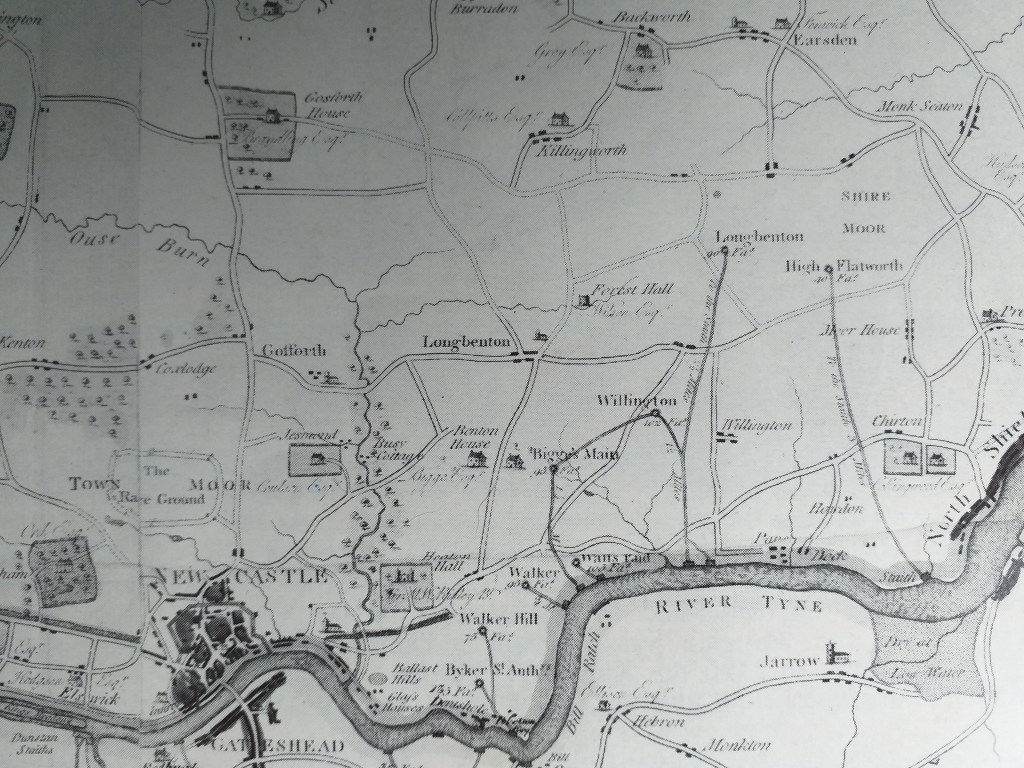

Look on a modern OS map of Tyneside and you will find the name ‘Bigges Main’, identifying an area a short distance along the Coast Road to the east of Heaton, within the grounds of what is now the Centurion Park Golf Course. For most local people today this rather strange sounding place name probably holds little meaning. The name actually derives from the pit village which existed in that area until it was demolished in the 1930s, which itself took its name from the colliery developed there in the 1780s. A previous article ‘The Master Sinkers Medal‘ focused on the sinking of Bigges Main Colliery and its subsequent development. This article explores the history of the pit village which was built to house its workforce and which for much of the 19th century had strong associations with Heaton.

Origins

The origins of Bigges Main village go back to 1784 when the mining partnership of Bells, Brown and Johnson arranged to lease the coal royalties of East and Little Benton, owned by Thomas Charles Bigge and others, in order to exploit the High Main Seam (a 2m thick seam of high quality coal which underlay the area). The colliery which they developed was initially called East and Little Benton Colliery but it later became known as Bigges Main Colliery (i.e. the colliery working Mr. Bigge’s Main Seam). At the same time the partnership leased land from Bigge for the colliery farm (an essential component of a mining enterprise at a time when many horses were used in mining) and for a village to house their work-force.

Why, you might ask, was it necessary for the colliery owners to build a village? In the second half of the 18th century the area between Newcastle and the coast was rural in nature and there was little existing housing available which could accommodate the employees of the new deep mines being sunk in the area. This made it necessary for the owners of collieries to build houses for their workforce. Bigges Main Colliery was a major undertaking which employed perhaps 400 men and boys at its peak. Taking into account associated family members this would mean finding accommodation for perhaps a thousand people, but none of the settlements in the vicinity were very big. Wallsend at that time had only recently seen the development of mining – the first shaft there reached the High Main Seam in 1781 and the 1801 census shows that the township of Wallsend had a population of only 1,312. Although the adjacent parish of Heaton had seen extensive mining in the past, this had ceased in 1745 and it would be 8 years after the opening of Bigges Main that the first of Heaton Main Colliery’s pits was won (1792). Even then, the development of housing for pitmen in Heaton was severely restricted, with only a small area of land allocated at each pithead. By 1841 the whole of Heaton had a population of only 220.

It appears from the colliery pay-bills which survive for 1784-86 that the owners started the building of houses at Bigges Main in the second half of 1785, shortly after the work on the colliery’s first two shafts was commenced. The company used several contractors who were already engaged on other work at the colliery for some of this work (including Thomas Brough, who had been undertaking a range of carpentry work, and Robert Atkinson, who had been carrying out masonry work on the building which would house the Engine Pit’s steam pumping engine). The first shaft was completed in November 1786 and it seems likely that the company would have sought to have some housing completed for the initial workforce by this time. Having accommodation available would have been important to attract workers.

Lay-out

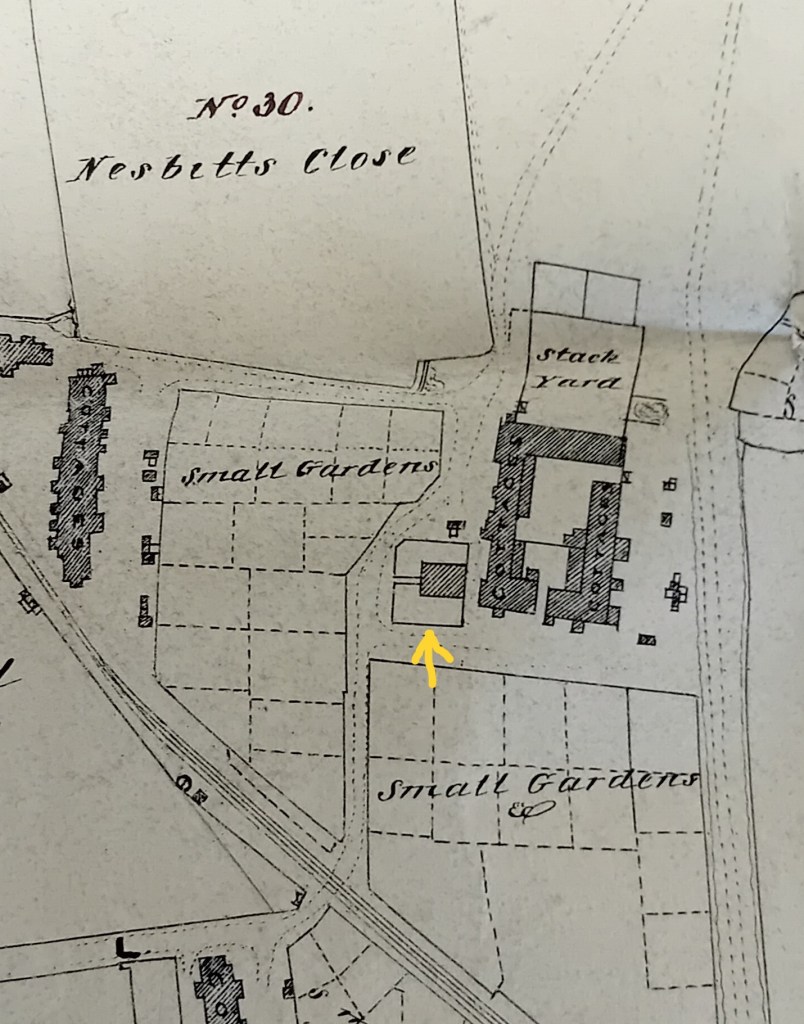

The North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineering’s archives include a document from 1808 which sets out the ‘Particulars of Houses at Bigges Main’ developed by the company. A total of 119 properties appear on the list although not all of these were at Bigges Main village itself. Seventeen of the houses listed were at the C Pit, located a kilometre north of the village (the remnants of its pit heap still exist there) and there were several at the B Pit, located near what is now Coach Lane.

The form of the village was essentially a square with its south-east quadrant missing and enclosed on only three sides. The eastern perimeter of the village followed the boundary between the townships of Little Benton and Wallsend which had a ‘dog-leg’ in it at this point. The square was a fairly common form for early colliery villages and it was not unusual for one side of the square to be left open. Another nearby example was Willington Square (aka Millbank Square), which was located further to the east (near what is now the Silverlink Roundabout on the Coast Road). It was also developed by Messrs Bells and Brown, at around the same time, to house some of their workforce in that area.

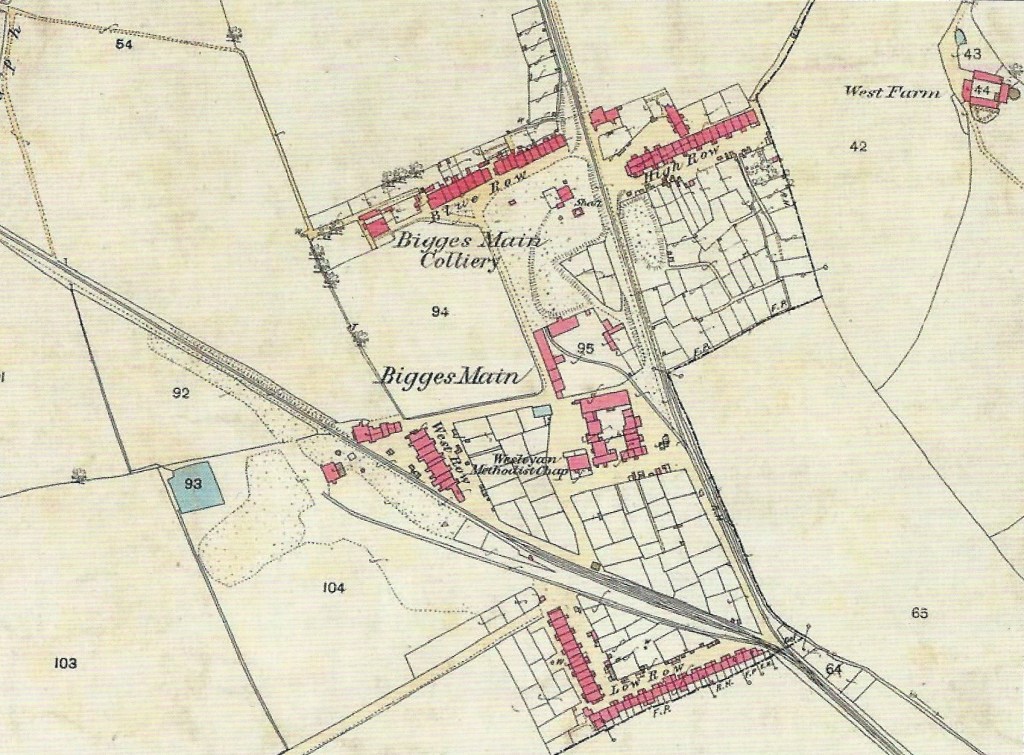

As the OS Map from 1853 below shows, five colliery rows (colloquially ‘raas’) formed the outer perimeter of the village and enclosed a substantial area containing a large number of allotment gardens and a central core of buildings which included cottages, colliery workshops and stores, some stables and a Wesleyan Methodist Chapel. Two pit shafts are shown, one to the western end of High Row and the other on the western edge of the village behind West Row. By this time both shafts had substantial adjacent spoil heaps.

The Bigges Main Waggonway (also known as the Willington Waggonway) is shown bisecting the village from north to south and the Coxlodge Waggonway cuts through the village diagonally from the north-west to join the Bigges Main Waggonway near the eastern end of Low Row (at times also referred to as Waggonmen’s Row). The Bigges Main Waggonway stopped operating in 1857 when the C Pit closed, but the Coxlodge Waggonway continued to convey coals from Coxlodge and Gosforth to the river until 1885 when the line was finally abandoned. The clanking of wagons passing through the village must have been a constant feature of life there up to that time.

Construction

The village houses were of brick construction with pantile roofs (such roofs were often used for roofing until the 1840s/50s when Welsh blue slates became available with the coming of the railways). It appears that the floors of the cottages were of bricks laid flat on beaten earth. The houses varied in size, with the largest being on Blue Row which had five houses in 1808, each having two front rooms and at least one back room on one level. Most of the other houses in the village had only one front room and a garret, an attic room used as a bedroom, which was accessed by a ladder pushed steeply through an opening in the upper floor joists (this arrangement persisted in at least some houses into the 1930s). Some also had a ‘toofall’ (a lean-to structure) at the rear. It is likely that the cottages, at least when they were built, would have had no ceiling in either the ground floor or attic rooms.

Water

There were a number of wells within the village which would have been the only source of water for much of the village’s existence (other than perhaps the collection of rainwater from the roof guttering in rain barrels). It seems the supply of water from wells was not always reliable. An old resident of the village, interviewed by the ‘Newcastle Evening Chronicle‘ in 1936, noted that drawing water from wells was somewhat of an adventure in summer when buckets would sometimes take from six in the morning to four in the afternoon to fill: ‘Sometimes the wells went dry altogether and then we had to fetch buckets of water from Wallsend’.

Exactly when outside water taps were provided is not clear. However, we know that another nearby pit village (at the William Pit, near Longbenton) did not get outside standing-water taps until the early 1900s. The village houses still had no internal water supply when condemned in the 1930s. Sanitary arrangements would have been basic. Human waste would have been collected, possibly at first by farmers from a communal midden (for use as fertiliser) and then by midden men. Systematic drainage was usually absent from such mining villages and contamination of water supplies was one of the main causes of outbreaks of typhoid and fevers in the colliery villages.

Access

Communication links with adjacent settlements, even by the later years of the 19th Century, were not very good. For most of its life the main access to the village seems to have been by a lane, called South Lane on Thomas Bell’s 1829 map of the Little Benton area, which ran eastwards from the Walker to Longbenton Road (today’s Benfield Road). This can still be followed on the ground but is now only a footpath running from the Cherrywood Estate and onto the former site of the Centurion Golf Centre. While in the 1890s villagers obtained many of their supplies from Wallsend, in 1895 ‘The Shield’s Daily Gazette‘ bemoaned that, except by trespassing on an old waggonway, which was obstructed in several places, there was practically no means of communication between Wallsend and Bigges Main. The path was said to be invariably covered with mud and water during winter months. It was only in the following year that the construction of a proper footpath was commenced, with the northern section funded by Mr Burn, the then owner of the village, with the southern section funded through voluntary subscription. The village would become more connected in October 1902 when the Tyneside Tramways and Tramroads Company opened a tramway between Wallsend and Gosforth, much of it laid along the site of the disused Coxlodge Waggonway. This service operated until 1930 when the economic downturn and the need for expensive track renewal led to its closure.

Pit Closure

Bigges Main Colliery operated initially between 1786 and 1809 at which point the economically exploitable coal in the High Main Seam was exhausted. It appears that on the surrender of the lease the colliery and all its associated buildings, including the cottages, reverted to the landlord, the Bigge family. In the years between closure and its reopening in 1836 the village would have accommodated workers from other nearby pits including those of nearby Heaton Main Colliery. It seems highly likely that that the village would have housed at least some of the men who were killed in the Heaton Colliery disaster of 1815. After it reopened in 1836 Bigges Main Colliery continued to operate until 1857. Analysis of the 1851 census undertaken by Les Turnbull found that the community at Bigges Main then consisted of 136 households containing 623 people. Nearly all the village men were employed in coal mining at that time.

The colliery closed in 1857 as a consequence of the flooding of the mid-Tyne Basin, an event which closed many mines in the area. The year 1857 was a very bad one for the Bigge family in another major respect. It saw the collapse of the Northumberland and Durham District Banking Company which meant ruin for the Bigge family as the major shareholders in the concern. These events led to the sale of their Linden, Little Benton and Willington estates. The Little Benton estate was auctioned in 1861 and the notices for the auction tell us that it consisted of ‘farms, dwelling houses and cottages, colliery village and gardens, the whole comprising about 398 acres of land’. The estate was bought by David Burn, a wealthy Newcastle businessman who was the joint owner of an extensive ironworks at Busy Cottage (now part of Jesmond Dene).On his death in 1873 his estates, including the Little Benton estate, passed to his son John H Burn. It appears that J H Burn exhibited a degree of paternalism towards his tenants with a newspaper reporting in January 1885 that he had ‘with his usual generosity, distributed 20 tons of coals amongst his tenantry at Bigges Main’.

With the closure of local collieries it became necessary for the owners to seek a more diverse range of tenants as illustrated by an advertisement placed in the Newcastle Courant in January 1862 by Burn seeking tenants or new owners for his Bigges Main holdings: ‘To Market Gardeners, Workmen and Builders. Plots of Ground, suitable for Market Gardens; Sundry Good Workmen’s Cottages, with Gardens attached, affording Good Accommodation for washing clothes; VILLA BUILDING SITES, with southern aspects, pleasantly situated at Bigges Main’. Analysis of the 1861 Census has shown that although there were still approaching 80 people in the village working in mining and related occupations, the total number working in all other occupations was greater. A wide range of occupations were now represented including some related to the iron making, chemical and shipyard industries developing along the river.

As more modern housing became available in areas like Wallsend and Heaton during the later part of the 19th Century the outdated properties in Bigges Main became less desirable and tended to be occupied by workmen in lower paid occupations. An article in the ‘Evening Chronicle‘ in 1896 highlighted the changing role of the village since the days local collieries were in full operation, noting that ‘It is now inhabited by the worst paid class of workmen employed in the mid-Tyne shipyards and engine works – men whose uncertainty of employment and low scale of wages prevent them from occupying the modern dwellings ….. erected in close proximity to the Tyneside industries in recent years‘

Church and School

It has not been possible to find documentary evidence for the date of establishment of the village’s Wesleyan Chapel. Wesleyan Methodism was definitely a growing force in the local area by the late 1700s and Wesleyan chapels were established at nearby Byker Village, in 1790, and Carville, by 1812. Whilst it is not known whether the Bigges Main chapel dates from this early period or was developed a little later, it existed by 1829 when it was shown on Thomas Bell’s map.

The parish church for the village was St Bartholomew’s at Longbenton, a distance of about a mile and a half, and the pathway leading from Bigges Main to Longbenton was referred to as Church Way. Later in the 1800s there are references to a Mission Room in Bigges Main and in the early 1900s a corrugated iron mission church was erected in the village.

The Wesleyan Chapel at Bigges Main seems to have played a key role in the early days of education provision in the village. In 1841, when the Childrens Employment Commission’s representative interviewed workers from Heaton Main and Bigges Main Collieries (at Bigges Main) evidence was given by the viewer of Heaton Colliery, George Johnson, that ‘at Bigges Main and Heaton there are a day school, with very good lending library, and an excellent Sunday school‘. It seems likely that this educational provision was located in the Wesleyan Chapel at Bigges Main.

Whellan’s History of Northumberland (1855) also mentions a school at Bigges Main, attended by about ninety children, which was ‘used as a place of worship, on Sundays, by the Wesleyan Methodist Reformers’. Methodists were highly committed to education and this may very well have been a Methodist run day school. Notably, in 1861 one of the residents of the village was Robert Reay who in the Census said he had two occupations: schoolmaster and local Methodist preacher. It should be remembered, of course, that before the 1870 Education Act many children did not attend school at all, and those who did averaged only a few years. George Johnson noted in 1841 that he did not allow children under 9 or 10 years of age to be trappers ‘although a strong desire for earlier employment exists amongst both parents and families’. He thought himself that ‘they would never make good pitmen if sent down later than 10 or 12’.

Later in the century the school passed into the hands of the Church of England and was connected with Benton Parish Church until Bigges Main was transferred from the Longbenton District to Wallsend in 1910. In 1934 the school, which had just two classrooms and still bore ‘the unmistakable stamp of its original use as a chapel’, was said to be not of the same standard as Wallsend’s other 12 schools. The school closed in September 1937 and its last 20 pupils were transferred to other Wallsend schools.

Allotments

The village’s extensive allotment gardens would have been important both as a source of food and recreation. An ‘Evening Chronicle‘ from 1896 commented that ‘The gardens attached to the dwellings are a great boon to the families, not a few of the tenants devoting the whole of their leisure hours to amateur gardening, a work in which many of them have attained considerable skill’. Around this time we find mention of the ‘Bigges Main Floral, Vegetable and Horticultural Society’ which ran an annual exhibition of vegetables, fruit and flowers.However, while the village seems to have had a strong tradition of gardening (one former resident described the gardens as “the pride of the village”) a report from 1895 said “it was much to be regretted that at Bigges Main, where gardens could be had for next to nothing, many of them lie in an uncultivated condition”.

It would be remiss, given the drinking culture which existed in pit villages, not to mention that the village had its own pub, ’The Masons Arms’. The pub outlived the village, not closing until 1968. The village also had its own football team, Bigges Main Celtic, which was in the Northern Amateur League. Frank Cuggy who played for Sunderland and England and went on to manage the Spanish side Celta Vigo, lived in the village and apparently played his first games for Bigges Main.

Last Years

The years following World War One saw a concerted effort to deal with sub-standard housing and the village’s days were numbered. The following quote from the Chairman of the Council’s Sanitary Committee in 1934 gives a grim picture of the conditions:’Actually Bigges Main is not a healthy place. The sanitary arrangements are not good. The houses are so old that they cannot be repaired. There are no water facilities in the houses. Some tenants have to walk the length of the street to get water from the tap. They are not paved and in the winter the place is something like a quagmire‘.

A former resident, Mrs Blackburn, interviewed in 1936, said ‘There can be no denying that conditions were prehistoric. They had never changed since the houses were built, with no indoor sanitation at all and with floors of bricks laid on soil-persisting even today’. The School Medical Officer meanwhile described the school as ‘a relic of the past‘.

One or two houses had already been pulled down by 1934 but it was not until 1936 that most of the population was relocated, largely to the Westmorland Estate on the north side of the Coast Road. This had been built specifically with the rehousing of Bigges Main residents in mind. Two of the streets on the estate, Bigges Gardens and Main Crescent, have names which recall the village.

What did the residents feel about having to leave? A report in the Newcastle Evening Chronicle in 1934 commented that ’Naturally, among the older people the fact that they will have to remove has caused a lot of concern and in some cases, bitterness. They claim the air is good in Bigges Main and it is healthy because of “being in the open”’. However, for many of the villagers, whilst the end of the village may have been in some ways a sad event, the prospect of moving to modern properties with proper sanitation and services must have been a welcome one. An interesting perspective was given by Miss Alexander, the former school headmistress who said ‘They took the houses down but they could never really claim that it was a slum area…It is true that the houses were old and dark but many of them were clean as little palaces’

It was reported in the press that last resident to depart the village in 1937 was Sarah Leonard, better known locally as Old Granny Leonard, who lived on High Row. She appears to have been quite a character and is said to have resisted moving to the Westmorland Estate. According to one local historian she ‘led the Council a dance’, but ultimately had no option but to leave the village. It is said that she made her final departure from the village on a milk cart with her possessions, no doubt a poignant journey for someone who had been born in the village in 1861 and lived there all of her life.

Aftermath

In the 1960s the site of the village was reclaimed to become part of a municipal golf course and in 1969 a sports centre was opened in the south west corner of the site. The sports centre burned down in 2015 and was subsequently demolished leaving only the golf centre on the site, although this is now itself under demolition. The golf course (now named Centurion Park) is currently closed and a major scheme to re-configure and improve it and provide new clubhouse facilities is underway. Nearby, on the site just to the south of what was the village, a new housing development, Centurion Chase, is also under construction.

There is little evidence on the ground now to show that the village of Bigges Main ever existed. The tree lined footpath which runs eastward from the Cherrywood Estate was once the main access to the village. Rheydt Avenue, which served the golf club and is now the access for the new housing development, follows the line of the old waggonway.

Acknowledgements

Researched and written by Alan Richardson of Heaton History Group.

Can you help?

If you have any further information about Bigges Main village or anyone mentioned in this article, have family connections with the pit or the village or have any relevant photographs, we would love to hear from you.

You can contact us either through this website by clicking on the small speech bubble immediately below the article title or by emailing chris.jackson@heatonhistorygroup.org

Sources

‘A Celebration of our Mining Heritage’ / Les Turnbull; Chapman Research in conjunction with the NEIMME and Heaton History Group, 2015

‘A Century of Education 1870-1970’ / North of England Open Air Museum, undated

‘The Colliery Cottage 1830-1915: The Great North Coalfield’ / H D Brown; unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Newcastle Department of Architecture, 1988

‘The Folks Alang the Road’ / A Senior; publisher unknown (1980)

‘History of the Parish of Wallsend’ / William Richardson; Northumberland Press (1923)

‘History, Topography and Directory of Northumberland’ / William Whellan & Co; Whitaker, 1855

Seymour Bell Collection (Longbenton Portfolio), Newcastle City Library

Various papers in The Common Room, North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers

Superb article Alan, thank-you.