This original print of a Thomas Bewick engraving is held by the British Museum. The museum’s catalogue describes it as a ‘rubbing’, the impression on paper of the reverse of a commemorative medal awarded by colliery proprietors Bells, Brown and Co to Matthew Tubman for winning East Benton Colliery ie successfully reaching the coal seam.

Chance Encounter

Heaton History Group’s Alan Richardson stumbled upon the catalogue entry while researching the development of mining in the Heaton and Longbenton areas. Intrigued, he wanted to know more about it.

Donation

The impression had been donated to The British Museum in 1882 by Isabella Bewick, daughter of Thomas Bewick (1753- 1828), the famous Newcastle engraver. It had been included in a donation of around 4,000 drawings and proofs of prints by her father, his brother, John, and his son, Robert Elliot Bewick. Subsequently, Alan found an image of the obverse of the medal in a book by Bewick expert Iain Bain and this showed that Matthew Tubman was a ‘master sinker’. Bain’s notes indicated that this was one of four medals which had had been commissioned by the colliery proprietors.

This is the obverse of the medal described by the British Museum as ‘Obverse of a commemorative medal, awarded by colliery proprietors Messrs Bells, Brown & Co to Matthew Tubman for ‘winning’ East Benton Colliery (successfully reaching a coal seam), with decorative border of garland; impression taken from silver. 1786′ (We have flipped the image on the British Museum website so that the text is readable).

The medal raised many questions for Alan, the foremost being where was East Benton Colliery as he could not recall hearing of one so named. His instinct was that this was an alternative name for one that he already knew (collieries often went by a number of names) and in due course this proved to be correct. He also wanted to know what a ‘master sinker’ did and why the colliery’s proprietors would have awarded him a medal. This article sets out the answers he found to these and other questions.

East Benton

Alan contacted Les Turnbull, another member of Heaton History Group and an authority on local mines and waggonways, who was able to confirm that East Benton colliery was better known as Bigges Main and that the medal was awarded in relation to the sinking of the Engine Pit, the first of a number of pits which would be sunk. (The term ‘colliery’ generally denotes a mining operation consisting of a number of pits.) The full name of the colliery, used in its early years, was actually the East and Little Benton Colliery.

By a remarkable coincidence, Les had seen and been able to photograph Matthew Tubman’s medal some years earlier, when it was brought into the North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers (NEIMME) where he volunteers.

The development of Bigges Main Colliery was part of a massive expansion of deep mining between Newcastle and the coast which took place in the second half of the 18C. This was driven by a growing demand for coal and the decline in mines to the west of Newcastle and facilitated by technological innovations, particularly steam-powered water pumps, which supported the mining of coal at a much greater depth than previously. In 1700 the deepest mines on Tyneside were about 300 feet (91m) but by 1750 they had reached 600 feet (183m) and by 1820 some pits reached 900 feet (274m).

In 1784 the partners in the enterprise, Matthew Bell, his son Richard, William Brown and George Johnson (an eminent viewer / colliery manager) entered into several leases relating to the coal royalties and land for the colliery farm and village.

William Brown was the son of the great mining engineer of the same name who had, before his death in 1782, partnered Matthew Bell for many years. The royalties were assigned on 12 May 1785 for 41 years. Messrs Bells and Brown already had other substantial mining interests in the area, including the Willington and Shiremoor Collieries, two of Northumberland’s largest. Johnson, who would act as the Colliery’s Viewer in its early years, also had other mining interests.

This detail of John Gibson’s map of 1788 shows Bigges Main and other important collieries of that time including Walker, Wallsend, Longbenton East and Willington, as well as their associated waggonways.

A village, also known as Bigges Main, was developed to house the workforce. This village, which no longer exists, was located less than a kilometre east of Heaton, its site now part of the Centurion Golf Course just across the boundary with North Tyneside.

Sinking and Sinkers

Once Bells, Brown and Partners had obtained the necessary leases they quickly began the work of shaft sinking. The first shaft to be sunk, the Engine Shaft, needed to reach a depth of 95 fathoms or 570 ft (173m). From the medal we know that it took almost exactly two years to complete.

Shaft sinking has long been considered a distinct occupation from others in mining and one of the most difficult and dangerous. In the 18C, sinking shafts was still achieved with hand tools only and the assistance of gunpowder; the sinkers would have been wound up or down a shaft with their materials, attached to the shaft rope or chain or in a corfe (a wicker basket). Apart from the obvious problems posed by gravity and restricted working space sinkers were often faced with the dangers of, among other things, toxic and explosive gases, water inundation, quicksand and falling debris. Blasting with gunpowder must have been a nerve-wracking business – once a fuse had been lit the sinkers would signal urgently to the men responsible for winding that they needed to ascend the shaft. Fuses at this time were not totally reliable and sometimes the explosive went off more quickly than expected.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that sinkers were regarded as an elite band within the mining workforce and colliery owners would be constantly looking to employ the most competent master sinkers to help plan, organise and lead sinking operations.

An early best practice manual for pit sinking and winning coal, ‘The Compleat Collier‘, published in 1708, stressed the need for sinking to be controlled by experienced sinkers : ‘….it is not every Labourer who has been (by chance) in a Coal Pit, or at Labour in other sort of digging above Ground, that is fit to be employed in this Work, but it should be one that understands the Nature of Stone and Styth, and Surfet, by some Experience had before in such sort of Labour…‘

In the northern coalfield it was common for sinking contractors to be employed directly by the colliery owners or their agents; a bargain would be struck between the parties covering the amount to be paid, terms and conditions, responsibilities for provision of materials, etc. It was common practice for sinking contractors and owners to agree on an amount to be paid for each fathom sunk. Master sinkers contracted in this way were regarded as employers in their own right, although they were not above carrying out manual work themselves. Contracts were advertised in the local press and the following appeared in the Newcastle Courant on 4 September 1784.

It is possible, given the timing of the advert and the fact that Shiremoor Colliery was part of Bells and Browns existing empire, that this advert related to Bigges Main Colliery.

Fortunately, extraordinarily detailed fortnightly financial accounts have survived for Bigges Main Colliery for the period July 1784 to December 1786, when the Engine Shaft was being sunk and other colliery infrastructure built. These tell us exactly who was involved in all aspects of the pits sinking and early establishment and how much they were paid. ‘John Tubman and Partners’ appear throughout the accounts from October 1784 to January 1786 receiving payments in respect of work on two shafts, the Engine Pit shaft and the Coal Pit shaft (the A Pit) the latter of which was commenced in January 1785.

John Tubman was clearly the man with whom the owners agents dealt, while Matthew, his brother, was presumably a partner in the business. In January 1786 a new bargain was struck, this time between the owners and ‘Broughs Tubman and Partners’, which covered the ‘sinking of the Engine pit and the keeping of the fire engine’ and this appears to have been based on £15 per fathom sunk. Six months later yet another bargain was agreed covering this work. Separate payments to Tubman and Partners appear in the accounts for ‘stopping waters in the Engine Pit’; water entering the shaft was a common problem encountered during sinkings.

Thomas and Barnaby Brough, the Broughs referred to in the later bargains, were engine wrights who seem to have been closely involved in the installation and ongoing operation/maintenance of the steam engines at Bigges Main as well as other aspects of the colliery’s infrastructure. A record exists in the papers of the Watson Collection of a proposal submitted by Barnaby and Thomas Brough, dated 24 August 1785, for making and fixing the materials for the large engine at East Benton Colliery (see below). They also submitted other proposals for work in the early years of the colliery.

We know that sinking of the Engine Pit commenced on 29 October 1784 and in the accounts for the fortnight ending 31 October the following entry appears: ‘ Given to Jn. Tubman to drink….1 (Shilling)’ . This was presumably given to celebrate the commencement of sinking work. For some reason work on this shaft seems to have been paused for much of the second half of 1785 and then recommenced in January 1786, to be finally completed in November 1786.

Because two of the bargains entered into for sinking of the Engine Pit also included the keeping of the fire engine (ie the steam pumping engine) it is difficult to know exactly what the sinking itself cost. However, total payments for all of the work total approximately £1150. In total four shafts would eventually be sunk in and around Bigges Main village: the Engine Shaft and the A, B and C shafts, the last of these being completed in March 1797. The Engine and A Pit shafts were located at Bigges Main Village; the B pit shaft not far from the junction between Coach Lane and the old Coxlodge Waggonway; and the C Shaft north of what is now the Regents Park estate. The remains of the C Pit spoil heap are one of the few surviving signs that the Colliery existed.

Celebrations

The winning of coal when a new shaft was sunk was the cause of great celebration for both colliery owners and their workforce. For owners the costs of sinking a shaft, or several shafts, as at Bigges Main, was a major expenditure incurred before any profits from a colliery were forthcoming. For a workforce, the completion of this task, often after several years of excavation, must also have been both a relief and a good reason for merrymaking. Exactly what celebrations occurred on the winning of Bigges Main Colliery is not known. However, the following report appeared in the ‘Newcastle Courant‘ on 4 November 1786: ‘Thursday there was great rejoicings in the neighbourhood of this town, on account of the winning of a valuable colliery called East Benton – Samples of the coal were brought into this town and highly approved of’. Reaching the High Main Seam was a big prize, the seam being 6 feet deep in this area and the coal of high quality.

Reports of celebrations at other pits perhaps give us a clue to how the winning in November 1786 could have been marked. In November 1775, Bell and Brown, along with another partner William Gibson, arranged celebrations when the Willington Engine Shaft reached a coal seam at 100 fathoms. Local Historian John Sykes recorded the event as follows in his Local Records; or Historical Register of Remarkable Events (1833): ‘ 2 November 1775: The new colliery, at Willington, near Howdon Pans, Northumberland, was won, on which occasion the owners gave a fat ox roasted, a large quantity of ale, and a wagon load of punch to the pitmen, sinkers, &c‘.

Another report, this time about celebrations following the winning of Percy Main Colliery in September 1802, illustrates how highly regarded the sinkers of this time were. The publication ‘True Briton‘ reported that a grand procession took place from the colliery to the staithes involving the pit owners, neighbouring gentlemen, the viewers, pitmen and other members of the workforce. The procession was led by the master sinker with a trophy, who was followed by the sinkers, four and four, with cockades. It goes on to say that: ‘All the workmen belonging to the colliery were plentifully regaled with beef and plum pudding, strong beer and punch, and amused themselves with music and dancing til a late hour‘.

How common it was for owners to mark the successful sinking of a pit by issuing medals is not clear, but another nearby example was discovered. When the Ann Pit was sunk in Walker in 1762 each sinker involved received an inscribed medal, although the design of these was not as elaborate as those awarded at East Benton. This sinking was notable in that it reached the High Main Seam at a depth of 99 fathoms; Walker Colliery was at this point the deepest on Tyneside.

It seems that there was also a custom of giving financial rewards on the winning of a pit. The author of ‘The Compleat Collier’ mentions that it was customary for owners to give sinkers ‘a Piece or Guinea, to Drink the good success of the Colliery, which is called Coaling Money…’

The owners of Bigges Main appear to have been pleased with the work undertaken by John Tubman and Partners. The accounts show that John Tubman was awarded £10 in December 1786 ‘on account of the coal being got earlier than expected’. Although we cannot be certain, it seems very likely that one of the four medals which were made would have been awarded to John. From a newspaper article which appeared a century later in the ‘Newcastle Chronicle’ we know that another of the medals was awarded to Thomas Brough, the engine-wright. In 1896, his medal was in the possession of a William Brough of Liverpool. A Thomas Brough of East Benton Colliery is recorded in the Longbenton Parish Register as being buried on 18 March 1795.

The Colliery

Bigges Main Colliery (i.e. the colliery working Mr Bigge’s main coal seam) was a substantial enterprise which would employ an estimated four hundred men at its peak. The colliery regularly produced 30,000 chaldrons (79,500 tons) or more making it one of the largest in the area. The highest yearly output seems to have been achieved about 10 years after the colliery was opened – the vend for the 12 months to 31 December 1795 was 40,151 chaldrons (approximately 106,000 tons). The Shipping Certificate below (also an engraving by Thomas Bewick) is for 60 chaldrons of ‘Bigge’s Main Best Coals’ which were dispatched from the company’s staithes at Wallsend on 13 August 1801.

The painting below gives us an impression of what a pithead of this period could have looked like, although in the case of Bigges Main, coal would not have been loaded on to wains or carts but directly on to rail waggons to be taken to the riverside at Wallsend via the Bigges Main waggonway.

Heaton Connection

Although Bigges Main lies just beyond the Heaton boundary, it later became closely connected with Heaton Colliery.

Bigges Main Colliery initially operated between 1786 and 1808 at which point it became uneconomic to continue mining it. The company’s leases for the coal royalties allowed it to terminate them at 12 months notice and they gave notice to give up the leases in March 1808.

Approximately 15 years later, in 1824, Johnson, Potts and Co, the operators of Heaton Colliery, arranged to lease the Little and East Benton Coal royalties. However, it would be more than a decade before Bigges Main Colliery was actually reopened. In the second half of the 1820s and first half of the 1830s the company’s main focus was on extracting the final reserves of economically workable High Main seam coal from the Heaton and Spanish Closes royalties and on reopening Benton Pit, which was located close to the Coxlodge Waggonway, which they did in 1825-26.

A report produced for the owners by the mining expert Matthias Dunn in 1834 tells us that at that time the D Pit of Heaton Colliery (aka the Middle Pit) was the only one of the company’s pits operating, although it was nearing the end of its life. It appears that production at Benton Colliery had been briefly paused at this time, although it still had extensive coal reserves (Dunn states that ‘the Royalties attached to this pit are those of Longbenton and Balliol College, bounded by Heaton, Bigges Main and the Main Dyke, in all about 300 acres yet unwought’) and while a substantial amount of work had been done towards reopening the Bigges Main C Pit and restoring its associated infrastructure, this was incomplete. However, the Benton and Bigges Main pits were clearly seen as being the main focus for the future of mining in the area.

Bigges Main was eventually reopened in 1836 and from this time it, along with Benton Colliery, became the focus of the enterprise and seem to have been worked jointly. Heaton Middle Pit was closed and Bigges Main village became the company’s administrative headquarters. This explains why, when representatives of the Children’s Employment Commission interviewed people from Heaton Main Colliery in April 1841, the interviews took place at Bigges Main village.

The detail below from John Thomas William Bell’s plan of the Newcastle Coal District in 1847 shows the Bigges Main C Pit and Benton Pit (named as Heaton Colliery), the associated waggonways and Bigges Main village.

Bigges Main Colliery eventually closed in 1857 as a consequence of the flooding of the mid-Tyne Basin which followed cessation of pumping at Friars Goose in Gateshead in 1851, an event which closed many mines in the area (Benton Pit was also affected, closing in 1852). Bigges Main village continued in existence long after the closure of the Colliery but it was eventually the subject of a slum clearance scheme in the 1930s after almost 150 years of occupation.

The Tubmans

Family history show that John and Matthew Tubman were both born at Heddon-on-the-Wall in the Tyne Valley, the son of another Matthew and Susanna Tubman. John was baptised in the village on 19 August 1744 and Matthew in around 1747. Heddon-on the-Wall was in the middle of an area of Northumberland which had long been important for mining.

Both brothers married and had children in Heddon-on-the Wall. John married Christian Robinson on 20 December 1766 and Matthew married Mary Robson on 19 March 1770. Matthew and John and their immediate families appear to have moved to the Longbenton area in the 1780s. They were obviously both very experienced miners who had presumably worked most of their lives in the collieries west of Newcastle but were, as many must have been, drawn to the area east of the town by new work opportunities as the centre of gravity of coalmining on Tyneside moved that way.

A Matthew Tubman is recorded as being buried in Longbenton on 26 May 1795 and if this, as seems likely, is the same man, he would have been around 48 years old when he died. No record has yet been found of John’s death, but it appears from the record of his wife’s burial in Longbenton on 22 April 1791 that he had pre-deceased her (she is stated as having been from East Little Benton, which is likely to be a reference to Bigges Main Village). Whilst to us it may appear that the two brothers died relatively young, in the context of life expectancy in the 18C this was not the case. Matthew’s wife, Mary, died on 2 June 1811 in Longbenton and is described in the Parish records as “widow of Matthew Tubman sinker”.

The Medal Maker and Engraver

It appears that Messrs Bells Brown & Co commissioned Newcastle silversmiths, Langlands and Robertson, to make the medals awarded at Bigges Main. In turn, Langlands and Robertson asked Thomas Bewick and Ralph Beilby’s engraving workshop to engrave the medals which they did at a charge of 11s 6d per medal.

When the medallions were made, in December 1788, Bewick had been in partnership with Beilby for over 10 years. He was at this time cutting blocks for ‘A History of Quadrupeds’, the first of the books which would help make him famous, but this would not be published until April 1790. The photograph below (reproduced courtesy of Les Turnbull) shows the reverse of the actual Tubman medallion.

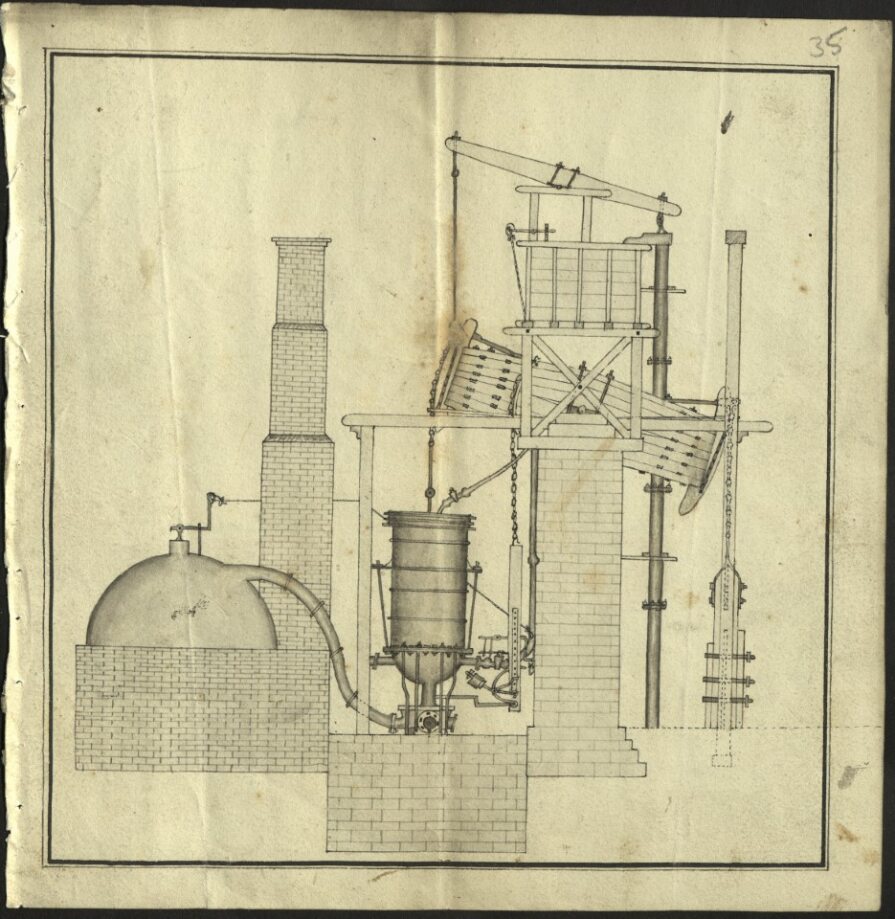

The image on the medallion is not the type of work we normally associate with Bewick. Research in the archives of the NEIMME led to the discovery of a plan of a Steam Pumping Engine which the engraving meticulously replicates. The Engine Shaft at Bigges Main was where the pumping engine was housed but whether this is a depiction of that engine or another, perhaps one designed by William Bell, is not known.

It should be remembered that Bewick himself came from a mining background. Bewick’s father rented a small landsale colliery at Mickley, together with a smallholding at Cherryburn. As a child Thomas worked as a gin driver at his father’s pit (a gin being a rope-winding device to which horses were harnessed, for raising the coal) and it is also clear from his Memoir that he was familiar with sinkers and aware of the hardships their work involved.

Tragedy

There is a sad postscript to this story concerning Matthew Tubman’s family. Matthew’s daughter, Mary, who was born at Heddon-on-the-Wall in December 1772, married Nicholas Gibson at Longbenton in May 1791. Tragically, three of their children, Matthew (aged 22), Edward (aged 20) and Nicholas (aged 18) – three of Matthew Tubman’s grandchildren – died in the Heaton Colliery Disaster of 1815 which killed a total of 75 men and boys. The three Gibson brothers were buried at Longbenton on 20 February 1816 along with four other victims of the disaster. The other victims were buried in St Peter’s Churchyard in Wallsend. Mary Gibson died at Bigges Main on 14 August 1820.

Acknowledgements

Researched and written by Alan Richardson of Heaton History Group. Thank you to Les Turnbull for his help and for his photograph of the medal. Thanks also to Jennifer Hillyard, Library and Archives Manager, the Common Room.

Notes

If your interest in sinkers and the art of sinking a coal mine has been piqued by this article you might be interested to read Les Turnbull’s account of the development of Willington Colliery (between 1773 and 1775) which appears in his latest book ‘The Willington Waggonway: a rival to the Stockton and Darlington’. The book also includes much more information about Bigges Main Colliery and the village of Bigges Main. It is available at most Heaton History Group talks or by contacting Arthur Andrews.

Can you help?

A further article focusing on the village of Bigges Main is planned. If you have any further information about anyone mentioned in this article, have family connections with the pit or the village or have any relevant photographs, we would love to hear from you.

You can contact us either through this website by clicking on the small speech bubble immediately below the article title or by emailing chris.jackson@heatonhistorygroup.org

Sources

‘A Celebration of Our Mining Heritage: A Souvenir Publication to Commemorate the Bicentenary of the Disaster at Heaton Main Colliery in 1815‘ by Les Turnbull; Chapman Research in conjunction with the NEIMME and the Heaton History Group, 2015

‘The Compleat Collier: or The whole Art of Sinking, Getting, and Working, Coal Mines, &c., As Is now used in the Northern Parts Especially round Sunderland and New-castle’ by JC;1708. Reprinted by Frank Graham, 1968

‘History of the Parish of Wallsend‘ by William Richardson; Newcastle Libraries and Information Service and North Tyneside Libraries, 1999

‘A Memoir of Thomas Bewick Written By Himself’ edited by Iain Bain; University Press, 1979

‘The Pit Sinkers of Northumberland and Durham‘ by Peter Ford Mason; The History Press, 2012

‘Thomas Bewick: Graphic Worlds‘ by Nigel Tattersfield; The British Museum, 2014

‘The Willington Waggonway: a rival to the Stockton and Darlington’ by Les Turnbull; NEIMME/Newcastle upon Tyne Centre of the Stephenson Locomotive Society/Archaeological Practice Ltd, 2023

Various documents from the NEIMME’s Foster, Johnson and Watson Collections located at the Common Room, Newcastle upon Tyne

That was incredibly interesting. Pit sinkers are indeed an elite band of mining engineers. I am researching Pitsinkers, this information has been very helpful.

My grandfather was a pit sinker at Maltby colliery 1908

Thank you for a fascinating article.

The reverse of the medal showing the pit engine differs in some details from the BM impression. Also, from that shown in the steam engine plan. On the medal, most obviously in the heavy vertical lines on the tower and pump base – there is no longer brickwork evident – and with etching(?) infill to the lower part of the image.

Is the impression I wonder, a proof before alteration of the medal, or does the impression relate to one of the other three medals?

Graham Carlisle (Bewick Society)

Well observed Graham. I’m afraid I don’t have an answer to your question but both of the possible explanations which you put forward sound plausible to me. I wonder if any other members of the Bewick Society might have any thoughts on this?