23 year old Georgina Graham escaped from northern France during the evacuation of allied forces from Dunkirk in 1940. It is thought that she may have been the only Tyneside woman to have been rescued as France fell to the invading German army.

It was while he was teaching his year 5 class about the Second World War and its impact on people in Heaton and around the world that local teacher, Jack Gardner, started to dig a little deeper into his own family’s experience and in particular that of his great aunt Ena. After interviewing his grandmother, Ena’s niece, and sifting through a large suitcase full of personal documents, photographs and newspaper cuttings, he was able to piece together at least the bare bones of her story.

Early Life

Georgina (Ena) was born on 20 May 1917 at 50 Stephen Street, Byker (behind the Cumberland Arms) to Samuel and Ellen Graham. Her father was a bill poster as was his brother, John, who lived with the family. Ena was the youngest of 6 children. But by the outbreak of WW2, there was only Ena, her mother and older brother, John, at home. The 1939 register, a mini census taken at the beginning of the war, shows Ena working as a ‘tin box machinist’.

Perhaps Ena worked at Metal Box at Heaton Junction. In the 1930s, Metal Box described itself as a ‘maker of plain and decorated tins, and tins for fruit and vegetables’. It made the first British beer can. But from 1939, everything changed and during the Second World War its products included:

‘140 million metal parts for respirators, 200 million items for precautions against gas attacks, 410 million machine gun belt clips, 1.5 million assembled units for anti-aircraft defence, mines, grenades, bomb tail fins, jerrican closures and water sterilisation kits, many different types of food packing including 5000 million cans, as well as operating agency factories for the government making gliders, production of fuses and repair of aero engines‘

Service

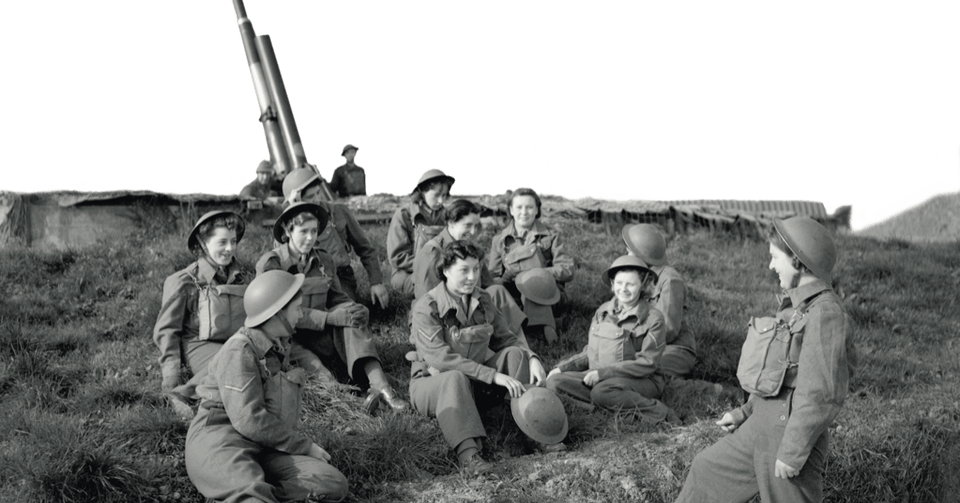

Ena’s life changed too. The Auxiliary Territorial Services had been founded in September 1938 when the threat posed by Adolf Hitler and the likelihood of war were only too apparent. It was intended that this new women’s unit would perform a range of support roles in the army, freeing up male recruits for the front line.

At the beginning women were employed as cooks, clerks, orderlies, storekeepers and drivers, although the range of jobs increased as more and more soldiers were sent to the front. It wasn’t until December 1941, following an underwhelming response to an Ernest Bevin speech at the City Hall in Newcastle on 9 March urging women to volunteer, that conscription for women started. At first it applied only to single women aged 20-30, but by mid-1943, almost 90 per cent of single women and about 80 per cent of married women were working in factories, on the land or serving in the armed forces. Ena, however, had joined of her own accord before war was declared.

When Ena was later asked what prompted her to volunteer, she said ‘Well, you felt you had to do something. It was either that or a munitions factory’. Whatever her motive, Ena was in the vanguard of the women’s army.

She recalled ‘At first I was attached to 5th Royal Northumberland Fusiliers, stationed down at Sedgefield Racecourse. We girls used to sleep on stretchers in the jockeys’ quarters. We were supposed to plot the height of planes and give directions but we didn’t have the foggiest. Then they asked for volunteers to go abroad and I put my name down. Don’t ask me why. Maybe I never thought I’d have to go.’

Part of a diary written by Ena during this period survives. She describes how, after initial training in Pirbright in Surrey, she and a colleague, ‘Volunteer Milburn‘, were selected from their unit to be part of a 300 strong ATS cohort to go to France. The pair were granted a period of home leave and then travelled to the former Ocean Hotel in Saltdean on the Sussex coast.

Ena says that the women were put through their paces by training officer Junior Commander Maxwell. She describes the kit inspections, medical examinations, lectures and physical education, including ‘sessions in the ballroom… special exercises for our legs and ankles in preparation for the cobbled streets of France’.

‘From 6am to 10pm we were at it…. We were all on tenter hooks to do the right thing in case we were eliminated from the draft, we were that keen to get to France’.

She goes on to describe ‘route marches along the grass covered cliffs in full kit. Gas masks at the alert, marching at the double… The last day we had this route march. It was a lovely sunny day – hard to think there was a war on – the skies so blue, the white gulls sailing above the winds, and the soft gentle breezes blew in from the sea below.’

‘Finally’ she says ‘our little lot – 25 of us – grouped around J/C Maxwell and had our photograph taken on the terrace. Then we were off, by truck to Newhaven where we embarked on the ——- to Le Havre / Dieppe.’

Western Front

Ena said later that she had gone to France at the start of April 1940 where she was employed in a hospital in Dieppe as a medical orderly attached to the Royal Army Medical Corps. She later said that there were 19 other British ‘girls’ working at the hospital. The idea was to allow more male soldiers to move into fighting roles.

‘It was just like being on holiday. We had our work to do but we also went out to restaurants and cafes.’

Others too have written that at first there were concerts, dances, French classes and games evenings and on 9 May 1940 a YMCA social club opened for those stationed in Nantes. But the very next day, the Germans invaded Holland and Belgium.

Almost immediately Dieppe itself began to be heavily bombed. Ena said ‘Air raid sirens began to sound regularly.’

Her diary recorded, ‘The nights are becoming frightening. It’s a great strain lying on our beds, gas masks at the alert… all feelings of security are gone.’

Refugees from the now occupied Holland and Belgium, many injured and traumatised, streamed into Dieppe. There was fear and confusion. ATS girls had to spend their nights ‘lying face down in a cold trench, bombs and bullets spinning and dipping in the thunderous air.’

Years later, Ena recalled that a birthday cake that she had been expecting from home failed to arrive. The story handed down through the family is that the boat carrying it was bombed and the remains of the cake, having washed up on a beach somewhere, was waiting for her when she got home!

What we do know is that hospital in which Ena was working was evacuated, with some ATS members transporting the sick and wounded to other medical facilities. Ena recalled travelling by train to Le Mans. Then ‘We marched with swollen feet and eventually slept on a bare and mouldy floor. The siren went as usual but nobody noticed… I don’t remember much about those last days. We spent about a week in Vitré looking after troops there. They didn’t have a rifle between them, I remember, and one of the guards we knew was killed by a Fifth Columnist and stripped of his uniform’.

Dunkirk

Calais fell on 25 May. Unbeknown to Ena and the other servicemen and women on the Western front, by then plans to evacuate the whole British Expeditionary Force had been in motion for almost a week. The troops were almost surrounded by the rapidly advancing German army and an audacious operation to rescue them from Dunkirk was being hatched. A flotilla of ships were already being assembled at Dover.

But it wasn’t until, on 26 May, prayers were offered ‘for our soldiers in dire peril in France’ in special services at Westminster Abbey and in cathedrals and churches throughout the country that the public became aware of the gravity of the situation. Just before 7 o’clock that evening Churchill gave the order for the rescue operation to begin.

‘We were hustled on and off a succession of lorries. We arrived at the beach in darkness, were hurried onto a boat and put straight into the hold,’ remembered Ena.

But the danger wasn’t over. Bombs were exploding all around them and a nearby boat was hit. The stern of Ena’s boat tipped up and bags of cocoa in the hold split open. Ena said that when she and her colleagues arrived back in England, they were covered in chocolate powder!

Joan Gardner, Jack’s grandmother, who was ten at the time, takes up the story of her Aunt Ena’s homecoming:

‘My Auntie Florrie used to live in Acton Place [in High Heaton]. I opened her garden gate one day. I looked over my shoulder and there’s my Auntie Ena coming round the corner dragging her kit bag… The front door opened. My Auntie Florrie and my nana FLEW out and grabbed Auntie Ena. They were all standing crying. I didn’t understand… They knew she was in the army but they didn’t know where she was. They didn’t know she’d been on the beach at Dunkirk, being evacuated… I’ve seen two films about Dunkirk. Not in either one of them was there any mention of women.’

Joan also remembered that Ena was upset that, on her return home, which was now on Holystone Crescent in High Heaton, nobody gave up their seat on the tram car and so she had to stand in her uniform with her kitbag. Her fellow passengers would not have known or expected that this young woman was on her way back from the evacuation at Dunkirk that they had read about in their morning papers.

Post-war

In April 1943, Ena married Andy Phillips and after the war, she worked for a garden nursery in Killingworth as well as behind the bar in both the Killingworth Arms and the Plough Inn. She became an active member of the Dunkirk Veterans Association, the only woman among 2,000 men. Ena was treasurer to the Newcastle branch and organised trips to Normandy for veterans of the evacuation. At one commemoration, she was unexpectedly reunited with a French nurse she had worked with in Dieppe all those years ago.

In October 1989, at the age of 72, Ena married for the second time. Her new husband, Owen Donaghy, was a fellow member of the Dunkirk Veterans Association. Like Ena, he had served with the Royal Army Medical Corps before being rescued from the Normandy beach.

Ena Donaghy died in 1994.

Casualties

Ena encountered great danger in the service of her country but she escaped with her life. Many women died while serving with the ATS at home and abroad. Well over a thousand are buried in cemeteries maintained by The Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Among them:

Private Lavinia Binns, who was attached to 167 (M) Heavy Anti Aircraft Battery, Royal Artillery, daughter of Edward and Lavinia Binns of West Jesmond, died on 28 December 1943, aged 25. Before the war, she was a grocer’s assistant. She is buried in St Andrews and Jesmond Cemetery.

Volunteer Margaret Black, daughter of James Walker Black and Mary Ann Black of Byker died on 20 May 1940, aged 20. She is buried in All Saints Cemetery.

Lance Corporal Florence Cross, attached to the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, daughter of John William and Rose Anna Brierley and wife of Albert William Cussack Cross of Byker, died on 8 October 1945, aged 23. She is buried in Byker and Heaton Cemetery.

Private Agnes Fitzpatrick, daughter of Arthur and Margaret Fitzpatrick of Longbenton, died on 16 July 1943, aged 25, and is buried in All Saints Cemetery.

Private Elizabeth Ada Lowther died on 13 March 1942. Her age, home town and family details aren’t recorded. She is buried in Byker and Heaton Cemetery.

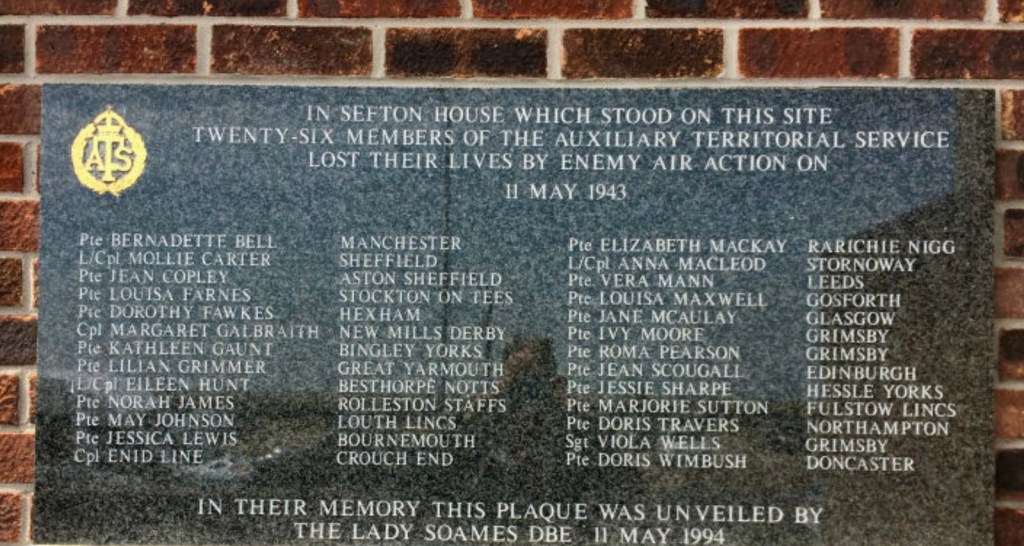

Private Louisa Agnes Maxwell, daughter of Mabel Winifred Maxwell of South Gosforth, died on 11 May 1943, aged 22. She is buried in St Nicholas’ Churchyard, Gosforth. Louisa was one of 26 ATS members killed on 11 May 1943 when the building in which they were billeted in Great Yarmouth was bombed. This was the worst loss of life of army women during the war. Louisa’s name appears on a memorial unveiled on the site (now the Burlington Palm Hotel) in 1994. In May this year (2023), events were held around the country to remember the women, including in St Nicholas’ churchyard.

Private Elsie Morgan, daughter of Alfred Henry and Jane Midgley Morgan of Walker and of the 2nd Continental Group, ATS died on 30 August 1945, aged 26. She was a transformer winder in 1939. She is buried in Brussels Town Cemetery.

Corporal Isabella Pace, daughter of John and Mary Pace of Wallsend, died on 1 October 1945, aged 24. She is buried in Munster Heath War Cemetery, Telgte, Nordrhein-Westfalen.

Remembering all the local women who served in World War 2.

Acknowledgements

Researched and written by Jack Gardner and Chris Jackson. With special thanks to Joan Gardner.

Can You Help?

If you know more about Ena Graham’s time in the ATS or the wartime experiences of anyone mentioned in this article, we’d love to hear from you. You can contact us either through this website by clicking on the speech bubble immediately below the article title or by emailing chris.jackson@heatonhistorygroup.org

Sources

Ancestry

British Newspaper Archive

‘Events honour 26 women killed in Great Yarmouth WW2 bombing’ BBC 14 May 2023 (retrieved 23 November 2023)

‘Joan Gardner talking about her Memories of World War 2’ Interviewed by Jack Gardner ; You Tube, 2023

‘Wartime Women: a Mass-Observation anthology 1937-1945’ edited by Dorothy Sheridan; Phoenix Press, 2000

Private papers of Jack Gardner

First published on 23 November 2023

Thank you for writing this. It was very interesting. And yes, we do need to remember the women who served

their country.

I enjoy reading articles on the Heaton History Group site. They bring back lots of memories.

Greetings from Carole in New Zealand.

Glad you enjoyed it, Carole.

My great aunt Dorothy Ethrington from Bishop Auckland County Durham was on the beach at Dunkirk, as a nursing auxiliary. She said the soldiers where so kind and help push them forward to get onto rescue boats.