Manchester’s infamous Peterloo massacre is rightly being remembered ahead of its bicentenary. But political protests weren’t unique to Manchester nor was Peterloo the earliest modern example of the military breaking up such a demonstration, leading to loss of life. Almost 80 years before Peterloo, Heaton miners were at the forefront of a less well known incident in Newcastle in which a Heaton landowner was also a key figure.

It has been argued by A W Purdue that the 18th century was a time in England when there was: “a social order which demonstrated considerable cohesion in that, despite acute social tensions, ‘acceptable compromises could be negotiated, compromises which safeguarded the social fabric'”.

There was indeed a strict social hierarchy, with the power in the land concentrated in the hands of a small number of men. In return for the compliance of the vast majority of the population with this arrangement, there was an expectation that there would be enough food for the general public. But what would happen, if there wasn’t enough food or the people couldn’t afford it? How would the population react and how would the authorities respond to that reaction? Events in Newcastle in 1740 give us some clues.

Background

There was heavy rain in August and September 1739, leading to a bad harvest, causing the price of oats and rye to double by June 1740. The winter of 1739-40 was also very severe. The Newcastle Courant carried reports of unemployment and shortages of food, coal and even water. Alderman Matthew Ridley of Heaton Hall is reported to have allowed the poor to collect small amounts of coals from his colliery in Byker. This was a heartening sign of compassion from a member of the Newcastle elite, but it was not a foretaste of what was to happen the following summer.

It has been reported that by March 1740, local food supplies were running short and there developed the widespread belief that speculators were hoarding grain to sell abroad at an inflated price. With less grain being available, so the market value went up drastically, to the point where miners in Heaton and keelmen on the River Tyne could no longer afford to feed themselves and their families.

There were riots in many parts of the country during May 1740, although at first those in Newcastle seemed insignificant: a small group of women, led by ‘General’ or Jane Bogey, apparently rang bells and impeded the passage of horses carrying grain through the town. Five women were committed for trial but discharged at Newcastle sessions a few days later and a regiment of dragoons on standby was withdrawn.

But disturbances continued elsewhere and, on 17 June, orders were sent for three companies of troops to march from Berwick to suppress troubles south of the Tyne.

Heaton miners’ dispute

On 19 June 1740, miners on the night shift at Heaton Bank pit went on strike in a dispute about their coal allowance, which may have been recently reduced by the owners.

By 3.00am, the men had garnered support from other pits and 60-100 of them marched into Newcastle, demanding a settlement of the price of grain, higher wages and better food.

Les Turnbull has noted that, ‘the affidavits record that the overman, George Laverick, “saw about 60 in Number of Workmen belonging to Heaton Colliery go past about 6 o’clock on Thursday morning”. Later, several hundred men, women and children joined the throng in Sandhill near the quayside.’

The following day, the miners were joined by keelmen and iron joiners from North and South Shields, with a crowd of several hundred descending on Sandgate. The authorities were alarmed by this and the Riot Act was read. The protest at this stage was mainly peaceful. A group of women and children did force their way into a granary with the help of some of the Heaton pitmen but in the main the protesters were just trying to put their case. Miners and the keelmen petitioned the city corporation and at first there seemed to be some sort of agreement to reduce the price of grain but when, the following morning, many grain stores failed to open, the mood of the protesters changed.

It wasn’t only miners who were involved. Keelmen were usually the protesters in those far-off days – they went on strike in both 1661 and 1731, arguably two of the first industrial strikes anywhere in the world.

It is instructive to see what happened in another north east town. Something similar happened in Stockton, but there the magistrates and aldermen sent letters to London, putting pressure on the government. Consequently, they averted major violence in Stockton. The magistrates in Newcastle decided on another path.

Magistrates’ response

The crowd of protesters soon grew to around 1,000 and they launched a full-scale attack on the granaries, with women and children again playing a prominent part, although even now they were peaceful and often persuaded to leave empty handed.

Many gathered outside the Guildhall, which was situated on its present site by the banks of the Tyne in the Sandhill area and at the northern end of the old Tyne Bridge, where the Swing Bridge is today.

Attack on the Guildhall

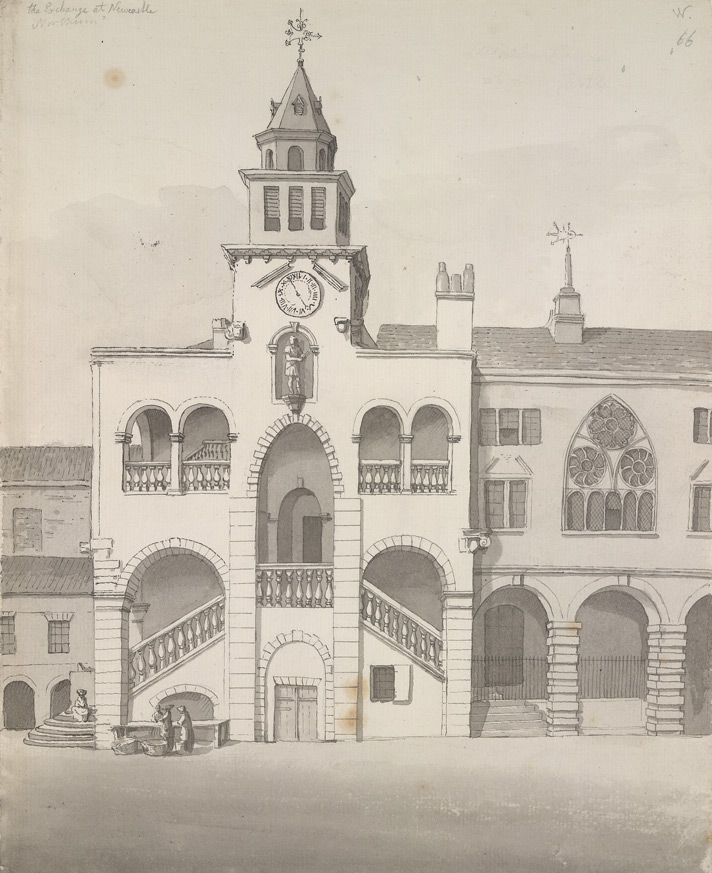

The violence escalated and the crowd, by now numbering at least 1,500, attacked the Guildhall, which was described at the time as a ‘very beautiful and sumptuous‘ building. (The building was not that with which we are so familiar with today. It had been built from 1655-60 by Robert Trollope, a mason from York, replacing an earlier building which had been damaged by fire in 1629.) It is recorded that the crowd of keelmen, iron workers and townspeople, ‘smashed the woodwork and windows, tore the paintings, and ransacked the archives and treasury.’ At least £1,300 was removed from the vaults but weapons that were captured were smashed and thrown in the river rather than used on the magistrates, all of whom escaped unharmed.

The actions that took place included the blocking of the movement of grain through the town, the seizure of grain and bread and unsuccessful negotiations with magistrates and merchants in an effort to reduce prices on a range of food items. There was also an attempt to commandeer a ship-load of rye. Interestingly, it has been noted that women and children were again prominent in the disturbances, but they were joined by contingents of pitmen, keelmen and iron-workers, as the food protest merged with discontent over wages and labour conditions.

Much of the anger was connected to the fact that corn and rye were being exported from the Tyne, from the towns of Newcastle and Gateshead, where people needed it. This was seen as going against the idea of a moral economy – more of which later. It has been noted that, ‘the transportation of grain from the Tyne and the Tees occasioned food riots there in May 1740. At Newcastle, women led protests against high prices and then attempted to unload a ship at the quayside. When an alderman, supported by a private army confronted them and fired upon the crowd, major disturbances followed.’

The private army of 60 horsemen and over 300 men on foot, all of them bearing oak cudgels, was led by Heaton Hall’s Matthew Ridley. At first it enforced an uneasy calm but the Grand Allies, who owned Heaton colliery, refused to cooperate, perhaps because it would mean coming into conflict with their own workforce but more likely because they could not bring themselves to work with Matthew Ridley, with whom they were often involved in bitter industrial and land disputes. There were other divisions among the authorities, too particularly between Alderman Fenwick, the mayor, and Ridley.

Over the following days, more and more people came into town to take advantage of the lower prices, which had been agreed earlier, but little grain was on sale. Eventually on 26 June, Ridley led a group of 20-30 armed freemen through the demonstrators. In the scuffling that followed, shots were fired. We know that at least one demonstrator was killed, possibly more, and others were wounded.

Understandably, the violence escalated. Ridley was so concerned that his home would be attacked that he bricked all his valuables away in a vault but, in the event, Heaton Hall escaped unharmed.

Mayor Fenwick had to appeal to the border garrison at Berwick to send more troops down through Northumberland before the protests were finally quelled.

Aftermath

The following day Matthew Ridley wrote a letter to the ‘Newcastle Courant’:

‘As it hath been maliciously reported that I was the first person that fired in the unhappy tumult yesterday, I think myself obliged to declare in this publick manner that I had neither gun or pistol in my hand nor did I give orders to any person to fire; but when the gentelmen were attacked in so violent a manner and several of them knocked down, they defended their lives in the best manner they could. Our intention at that time was to guard the delivery of the ship lying in the key laden with rye at the low price and to protect the poor upon the terms promised last Saturday’

Ninety one ringleaders’ names were collected for their part in the disturbances on 19 and 20 June, 41 of which were pitmen, seven waggonmen, seven keelmen, six women, five tradesman, one labourer and 24 of unknown occupation.

Eventually twenty pitmen, predominantly from Heaton, were indicted. Most escaped punishment as the authorities chose to respond with moderation, although there were two convictions for felony, with sentences of seven years transportation, and one of riot, with a sentence of six months in prison and a further twelve months ‘on securities’.

Among the Heaton miners were William Dunn of Gateshead, who worked under Ralph Laverick, Thomas Clough of Gateshead, who worked under George Claughton and Robert Clewett of Sidgate, who worked under John Taylor. There was also George Clewett of Gateshead, who worked under George Claughton, John Todd, who worked under Henry Laverick and William Richardson, who worked under Ralph Weatherburn. This suggests that men came from quite long distances to work in Heaton.

A further 213 men were identified as being involved in the disturbances on 26 June, 112 of whom were prosecuted, but again the punishments were relatively lenient, perhaps influenced by the fact that most local collieries had gone on strike while awaiting the verdicts.

The Guildhall was not, in fact, completely destroyed but, following further damage by fire, the frontage was rebuilt in 1794 to designs by William Newton and David Stephenson. In 1809, the south side was redesigned again in a classical style by John and William Stokoe. John Dobson’s east extension was completed in 1823.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Matthew Ridley failed in his bid to be elected to Parliament as a Member for Newcastle in 1741 but he was elected unopposed in 1747. He was also mayor of Newcastle in 1745, 51 and 59. Interestingly in May 1768 he spoke in Parliament in defence of Newcastle men involved in London riots and against the use of the militia in riots.

Reflections

It has been noted that two distinct views of the riot prevailed afterwards; ‘The outbreak of popular violence confirmed some people’s suspicions that “respectable” grievances served only as a pretext for the mob’s brutish desire to loot and plunder: to others it vindicated the traditional argument that it was not only unjust but also unwise “to provoke the necessitous, in times of scarcity, into extremities, that must involve themselves, and all the neighbourhood in ruin”’.

When E.P. Thompson wrote in 1971 about the Newcastle Corn Riots of 1740 in his famous paper The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the 18th Century, he talked of how the moral economy had been disturbed. Here is a definition of moral economy from the Oxford Dictionary online: ‘The regulation of moral or ethical behaviour; an economic system in which moral issues, such as social justice, influence fiscal policy or money matters.’

Thompson argued that the merchants and magistrates had disrupted the idea of the moral economy by not listening to the arguments of the working people that they could no longer afford rye and bread at market prices. Here was a sign of the beginning of the modern capitalist economy where items would be sold at the market value and the idea that there should still be a moral economy – which, it has been argued, in one interpretation, ‘is an economy based on goodness, fairness, and justice. Such an economy is generally only stable in small, closely knit communities, where the principles of mutuality — i.e. “I’ll scratch your back if you’ll scratch mine” — operate to avoid the free rider problem’ – was being lost.

As the economy of the north east grew during the 18th century, so society was moving further and further away from the older ideas that those at the top of the social hierarchy should be paternalistic towards those lower down the pecking order. As the market value of commodities became more important to those in positions of power than a sense of responsibility to those who would have been called the ‘lower orders‘, so it is argued, working people increasingly protested, especially when faced with starvation.

It is perhaps, then no wonder that the coming years would see the hierarchy itself being increasingly challenged but we shouldn’t forget the Newcastle corn riots of 1740 or the parts played by Heaton miners – and the local landowner.

Acknowledgements Researched and written by Peter Sagar with additional material by Chris Jackson.

Sources

‘A Celebration of Our Mining Heritage ‘ / Les Turnbull; Chapman, 2015

‘The Guildhall’, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 1952

‘The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century’ / E P Thompson; Past and Present, No. 50. (Feb, 1971), pp76-136

‘Newcastle in the Long Eighteenth Century’ / A W Purdue; Northern History, September 2013

‘The Politics of Provisions: Food Riots, Moral Economy, and Market Transition’ by John Bohstedt; Routledge, 2010

‘Popular Cultures in England 1550-1750’ / Barry Reay; Routledge, 1988

‘Riotous Assemblies: Popular Protest in Hanoverian England’ / Adrian Randall; OUP, 2006.

‘Urban Conflict and Popular Violence: the Guildhall riots of 1740 in Newcastle upon Tyne’ / Joyce Ellis; International Review of Social History, Vol 25 Part 3, 1980.

https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/us/moral_economy

https://everipedia.org/wiki/Moral_economy/

http://englandsnortheast.co.uk/Georgian.html

https://co-curate.ncl.ac.uk/guildhall/

A truly superb work of social and industrial history; in every way an education of contemporary value. Thank-you folks, it is much appreciated. P.S. Perhaps Les Turnbull might post the pertinent extract from his book (Coals from Newcastle) regarding the deplorable behaviour of Ridley in regard to Cotesworth’s legal claim to Heaton coal.

Thanks Keith for your kind words….much appreciated!

Thank you, Keith! We’ll ask Les.

This is fascinating and a window into a world on the cusp of feudalism and capitalism. Good to see you’ve been busy since I bumped into you at Killhope a year ago