The streets of Heaton and High Heaton are familiar to most visitors to this website but have you ever wondered what was here before they were built in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries? Eminent local historian, Mike Greatbatch, has been looking at surviving records to help us find out what Heaton was like 210-225 years ago:

The township of Heaton, like all the townships in Northumberland, owes its existence to the Settlement Act of 1662 which stipulated that the northern counties of Lancashire, Cheshire, Derbyshire, Yorkshire, Northumberland, Durham, Cumberland and Westmorland, `by reason of their largeness of the Parishes within the same’, should henceforth be subdivided into townships for the better administration of the `the Poor, Needy, Impotent and Lame’ (13 and 14 Charles II c12 Settlement).

Whilst the township boundaries may have mirrored those of some major landowners in 1662, it should not be confused with these private estates. Townships were administrative districts created by parliament to levy the poor rate and disburse the available funds to relieve the poor. Consequently the township boundary of 1662 continued to define Heaton as a district for the next two hundred years, well beyond its incorporation into the Town and County of Newcastle in 1835. Only when the population of Heaton and Byker townships began to grow rapidly towards the latter half of the nineteenth century did the old boundaries become indistinct, with ward boundaries based on the changing size and distribution of Newcastle’s municipal electorate becoming the norm.

The Poor Rate

Heaton township was created to better administer the poor rate. This was a tax based on an assessment of the yearly value of property, defined by the annual rental paid by the occupier. Heaton township lay within the parish of All Saints, and surviving records show that the poor rate was supervised by the magistrates and administered by the parish vestry, whose members appointed and employed the overseers of the poor from amongst the ratepayers of the parish, and administered all collections of the rate and its disbursement.

The rate assessments were agreed at regular meetings to cover specific periods and purposes, being recorded in Rate Books along with a list of properties, their occupiers, and their rentals. The rate itself varied from time to time depending on changing levels of demand for poor relief and other associated expenditure, such as overseers expenses.

The number of surviving rate books for Heaton is very limited: the catalogue at Tyne and Wear Archives lists just three volumes between 1860 and 1890. However, within the records of the neighbouring township of Byker there is a detailed assessment that includes Heaton. Recorded in March 1795, this was specifically `a taxation for the purpose of procuring (jointly with the Township of Heaton) a Volunteer, to serve in His Majesty’s Navy during the present War’. A rate of two pence per pound was calculated to raise £20 10s 3d from Byker and £18 11s 8d from Heaton in the following month of April. At the end of the assessment, there are the signatures of the Overseers of the Poor for both townships, which for Heaton was Thomas Holmes, a farmer.

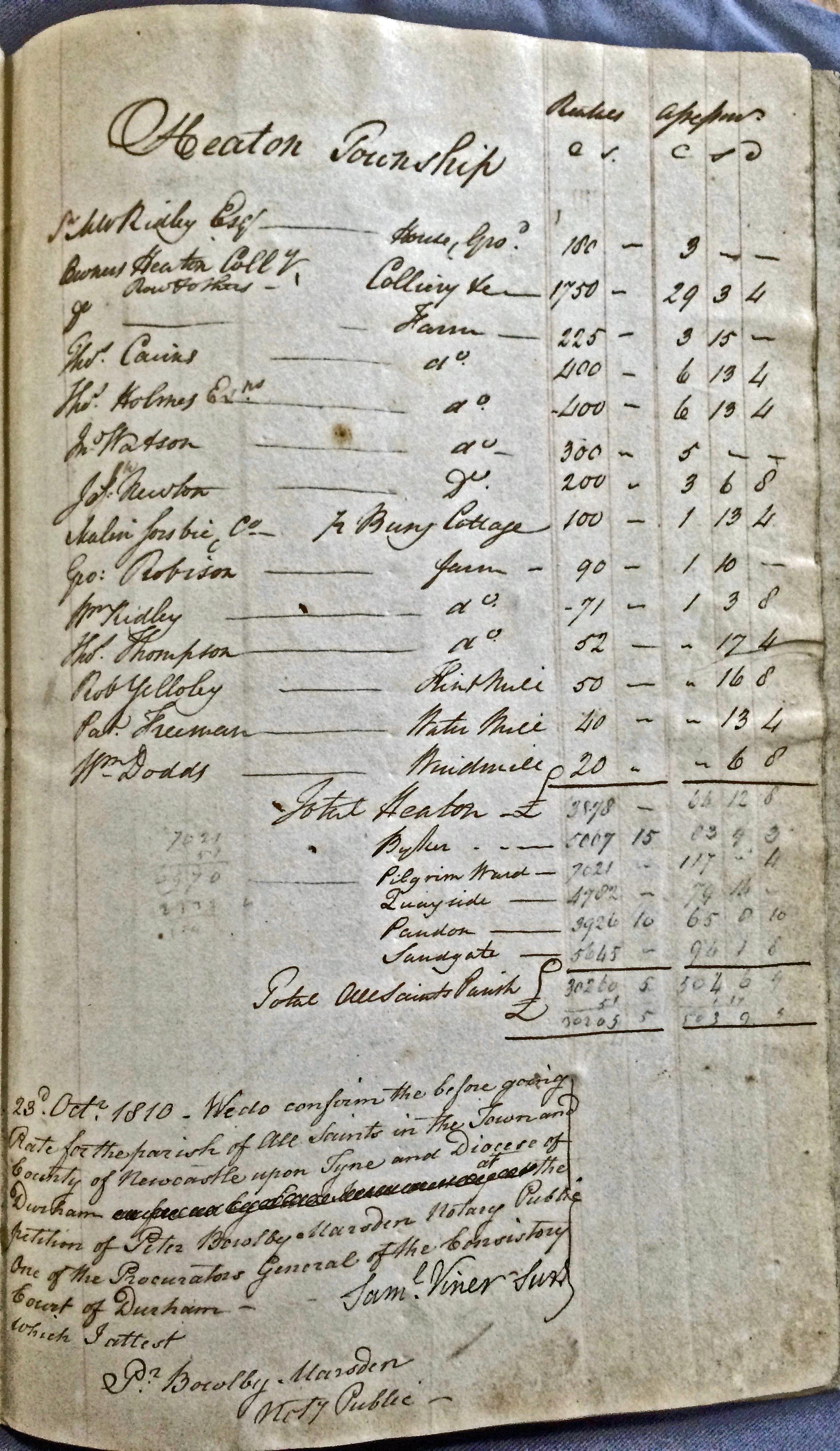

A similar detailed record also survives within the rate books for the parochial chapelry of Newcastle All Saints. Undertaken in October 1810 for the purpose of raising `the sum of four hundred pounds and upwards’, being the sum required to `reimburse the Church Wardens for the money expended by them for the Bills, Clerks Salary, Bread, Flour, Visitation Charges etc and to enable them to keep the Church thoroughly clean and in repair and other incidental expenses’. A rate of four pence per pound was levied, calculated to raise a total of £503 from the whole parish, of which £93 09s 3d would be raised in Byker and £66 12s 8d raised in Heaton. At the end of the assessment, the signature of Samuel Viner, a magistrate (`his Majesty’s Justices’) and Peter Marsden (a public notary acting on behalf of the church) are recorded, confirming their consent to the agreed rate, together with the date they attached their signatures to this declaration, 23 October 1810.

Taken together, these two detailed records illustrate the nature and changing value of property in Heaton during these years, together with the names of those whose income permitted them to occupy these premises as tenants of the two principle landowners at that time, Matthew Ridley and Sir Matthew White Ridley. The latter lived at Heaton Hall on land owned by the former and ,in 1795, the rental value of the house and grounds was £60, rising to £180 in 1810. Whilst this is the only house identified in the rate assessments, the farmhouses were included in the overall value of the farm rentals, and likewise the cottages occupied by the labourers. The working poor did not own property and thus they are absent from both assessments.

Coal and Iron

The population of Heaton recorded in the first detailed census carried out on 10 March 1801 was just 183 persons. By contrast, the population of neighbouring Byker was 3,254 persons. Byker was far more industrialised than Heaton by 1801 and this is reflected in the rate assessments undertaken in 1795 and 1810. Industrial property was present in Heaton in both years but its share of the total value of property was significantly less than in neighbouring Byker.

Heaton Colliery was the most valuable property in Heaton. In March 1795 it was valued at £1000 annual rental, increasing to £1,750 per annum by October 1810. This one industrial concern accounted for at least 45% of the total value of the property in Heaton recorded in both years.

Other industry in Heaton accounted for a mere 5% of the total value in both 1795 and 1810, despite the significant increase in value of Malin Sorsbie’s iron-works at Busy Cottage, from a rental of £30 per annum in March 1795 to £100 rental in October 1810. In neighbouring Byker the contrast couldn’t be greater. Here industry other than coal mining and associated transport accounted for 15% of the total in 1795 and 41% of the total value in 1810.

The iron-works at Busy Cottage (where Jesmond Dene’s visitor centre and Pets’ Corner are now) had long been a significant industrial settlement in Heaton. When it was advertised for sale in 1764, following the bankruptcy of its then owner, George Laidler the younger, this settlement adjacent to the east bank of the Ouseburn consisted of a dwelling house, three houses for servants and workmen, a stable with two parcels of ground adjoining, an over-shot forge and bellows wheel, a furnace for making iron, and facilities for making German steel. There was also a tilt hammer for making files and other items from thin iron plate, and a grinding mill with up to seven grindstones, a machine for cutting dyes, and a slitting mill for cutting and shaping bars of iron, all powered by over-shot waterwheels or water powered engines.

There were also extensive smiths shops that could employ up to fourteen workmen using three hearths, plus a foundry for casting iron and a steel furnace capable of producing about four tons of steel every nine days. When the premises were advertised again, two years later, there were an additional thirteen smithies, several warehouses, and a `Compting-house’ (counting-house) or office.

From January 1781, Busy Cottage was owned by the owners of the Skinner-Burn Foundry, Thomas Menham and Robert Hodgson, and when they became bankrupt in January 1785, Busy Cottage once again was advertised for sale, being `well adapted to carrying on the nail, hinge, ….file cutting, or any other branch in the smith and cutlery way’. The complex also included a water-powered corn mill at this time.

Although advertised for sale again in the summer of 1790, Thomas Menham is still recorded as living at Busy Cottage in January 1793, so Malin Sorsbie had not long been in possession of the property when he was recorded as occupier in the March 1795 rate assessment.

The Sorsbie family had long been prominent amongst the business and municipal community of Newcastle; a Robert Sorsbie served as mayor in the 1750s and Jonathan Sorsbie later served as Clerk of the Council Chamber. In the 1760s the family business interests included grindstone quarries on Gateshead Fell and a foundry at a site on the south side of the Tyne called the Old Trunk Quay, in addition to their corn merchant business with offices at Sandhill. Malin Sorsbie owned a house and garden in fashionable Shieldfield from at least January 1789 onwards.

Mills: Water & Wind

If Heaton Colliery and Busy Cottage were the highest value industrial property in Heaton, this does not diminish the importance of the other three industrial enterprises active in these years. All three followed the upward trend in value between 1795 and 1810 and were an important feature of the township beyond this period.

The precise location of Robert Yellowley’s flint mill is uncertain, but should not be confused with the similar establishment on the west side of the Ouseburn in Jesmond. The Yellowley family were merchants, and by the 1790s Robert Yellowley was wealthy enough to afford the rent on a house at St Ann’s Row on the New Road, west of Cut Bank. When the Ouseburn Pottery of Backhouse and Hillcoat ran into financial difficulty in 1790, Robert Yellowley acquired the business and is recorded as proprietor from June 1794 onwards. Flint by this time was an essential ingredient in the manufacture of better quality earthenware as it turns white when burnt, and thus provided a bleaching agent when used in firing the ware.

Heaton windmill was in the occupation of William Dodds throughout these years and, like the watermill occupied by Patrick Freeman in October 1810, it was an important adjunct to the eight farms that occupied the greater part of the land in the township. Identifying the precise location of Freeman’s watermill is not easy. In a schedule of land prepared by the surveyor John Bell to accompany a plan of West and East Heaton in December 1800, there are three mills – High, Middle, Low – identified in fields adjacent to the east bank of the Ouseburn. However, in 1810, Freeman’s is the only mill specifically identified as water powered, so it may be that the other two were dormant and unoccupied. In the 1795 rate book, this property appears to be occupied by Richard Young but again little indication is provided as to its location.

Heaton’s Farms, 1795 and 1810

In the October 1810 rate assessment there are eight farms, which together had a combined value of £1,738 or 45% of the total rental value of the township. The families who occupied those farms were the same as in March 1795 with the exception of William Lawson who had died in January 1804. In 1810, Lawson’s farm was occupied by John Watson.

The most valuable farms were High Heaton Farm (the Holmes family), Lawson’s farm, the Newton family farm in Low Heaton, and Thomas Carins’/ Cairns’ (the spelling varies throughout this period) farm. Some indication of their social and economic standing is provided by the fact that Thomas Holmes was the township’s Overseer of the Poor in 1795, and Cairns the treasurer of the local Association (for Prosecuting Felons). This Association combined with similar associations of property owners in neighbouring Gosforth and Jesmond to offer cash rewards to anyone providing information that helped secure a conviction for theft, damage or trespass, and/or the return of stolen property. They also published appeals to their fellow property owners and hunt enthusiasts to avoid damage to crops and `not to ride amongst corn or grass seeds’.

All these farms were extensive undertakings, and given the sparse population of Heaton at this time, all were vulnerable to theft. When Lawson’s farm was broken into in 1790, thieves stole hens, geese, and poultry, and made off on a mare that returned to the farm the same night. In the summer of 1795, twenty-three chickens, six hens and two cockerels were stolen from a single hen-house in Heaton; a reward of two guineas was offered by William Pattison of Heaton, with a further reward of three guineas paid by the Gosforth Association on conviction. When Joseph Newton’s garden was broken into in July 1808 and a quantity of fruit stolen, causing injury to the trees, a reward of twenty guineas was offered by the Heaton and Jesmond Association, Newton being one of its members.

If apprehended, those convicted could face severe punishment. In October 1798, Joseph Nicholson, William M’Clarie, Jane Cunningham, and Mary Eddy were all sentenced to six months hard labour for having stolen rope from Heaton Colliery. Given the need to store ropes, screws, bolts and other iron materials, the colliery was a regular target for thieves. As incidents of infringements of property rights increased, so the punitive nature of these associations became more pronounced.

Conclusion

In March 1795, the total value of property assessed for the poor rate in Heaton Township was £2,136. By October 1810 the total value of the same property was £3,878; being an increase of 81.5%. Despite the on-going war with Revolutionary France and its allies throughout this period, the local Heaton economy experienced something of a boom period.

The interdiction by French naval ships or privateers of merchant ships importing grain and other foodstuffs to the Tyne resulted in a food shortage, especially of wheat and rye. In 1799, the resultant scarcity of flour led some local newspapers to recommend rice and potatoes as good substitutes by way of relieving the distress prevalent amongst the town’s poorer inhabitants.

This scarcity also resulted in an increase in the price of grain and locally milled flour. Despite the accumulation of imported grain in temporary wooden stores, soon commonly referred to as Egypt, just west of Saint Ann’s Church in the summer of 1796, the price of wheat, rye, barley, and oats all increased from 1798 onwards. This of course was good news for farmers, millers, and landowners in townships like Heaton where transport costs to the local Newcastle market were negligible.

One might think that as their income and property values increased, the respectable residents of Heaton might relax their attitude to their neighbours in the manufacturing districts of Sandgate and Byker. Sadly, the opposite appears to have occurred. As the wartime economy and interruptions to overseas trade increased the numbers of those without work or on low income, so the property owners of Heaton became increasingly conscious of the vulnerability of their privacy and possessions. Unemployment, food shortages, and widespread human distress made the sparsely populated lanes and fields of Heaton all the more attractive to those desperate for redress and with little to lose.

In June 1805, a blacksmith named Erington was stopped near Heaton Wood by a man dressed in a blue jacket and robbed of a £20 bank note. Such incidents of so-called foot-pads became a recurring feature of Newcastle newspaper reports as the number of homeless seafarers and unemployed workers increased. The response of the local associations of property owners was characteristically harsh, resulting in the following all encompassing resolution by the Gosforth (& Heaton) Association in November 1805 `to prosecute with the utmost rigour, all vagrants, or other disorderly strollers, and those who give them harbor or encouragement’. By the first decade of the nineteenth century, even going for a stroll, in Heaton, had become a dangerous pastime.

Sources & Acknowledgements

Written for Heaton History Group by Mike Greatbatch. Text copyright Mike Greatbatch and Heaton History Group. Image permissions from Tyne and Wear Archives for use on this website only.

The surviving rate assessments for these years are part of the collections at Tyne & Wear Archives, specifically 183/1/577 Byker 1794-1802, and 183/1/102 Newcastle All Saints June-November 1810.

Contemporary trade directories and Newcastle newspapers, specifically the Courant, the Advertiser, and the Tyne Mercury provided details of properties and owners, together with reports on the human impact of wartime food shortages and the response of property owners through the various Associations. Many of the newspaper sources were accessed on-line via the British Library’s invaluable British Newspaper Archive.

The author is grateful to staff at both Tyne & Wear Archives and Newcastle City Library Local Studies & Family History Centre for their help in accessing sources and for permission to reproduce the two images.

Well done Mike; thank-you. Puts flesh on the bones of Heaton’s sparse history outside of the Hall. I’ve got Frank Graham’s field plan for Heaton somewhere, I’ll look it out and send it to Chris.

Many thanks for this useful information about the Mills in Heaton. The William Dodds mentioned is my direct ancestor. His son Edward was a butcher/grocer/beer retailer on Shields Road. I believe in the mid to late 1800’s he started the Butchers Arms pub on Shields Road in Byker, which I have visited a few times when visiting from New Zealand.

Kind regards

Richard Dodds

New Zealand