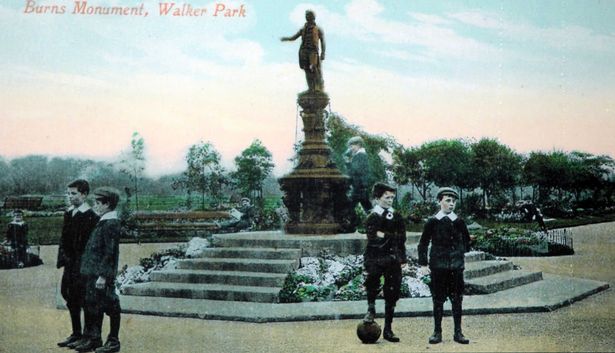

Who remembers a statue of Scottish poet, Robert Burns, in Heaton Park between the mid 1970s and mid ‘80s? It seems that, even among those of us who lived in Heaton back then that not many people do, which is something of a mystery. We are hoping that this story of the statue and how it came to be in Heaton will jog some memories and maybe even unearth a photograph or two.

On Tour

Robert Burns was born in Alloway near Ayr and later lived less than 30 miles from the border in Dumfries, so it’s perhaps surprising that he only visited England, or indeed left his native Scotland, three times, all in the same month, May 1787, while on a tour to collect orders for a collection of his poems. On two occasions, he ventured only a very short distance over the border to Coldstream and Berwick but on the third occasion he came to Newcastle via Wooler, Alnwick, Warkworth and Morpeth.

To Newcastle

The date of the poet’s visit to Newcastle was Tuesday 29 May but unfortunately, although Burns kept a diary, it doesn’t give us any clue to the route he took through the town, where he stayed or what his impressions were. He recorded only that his party met ’a very agreeable and sensible fellow, a Mr Chatto, who shows us a great many civilities and who dines and sups with us.’

A letter, written during his brief stay, to his friend, Robert Ainslie, who had originally been with the group but had returned home, suggests he wasn’t particularly happy while he was here. Burns wrote, ‘Here am I, a woeful wight on the banks of Tyne. Old Mr Thomas Hood has been persuaded to join our Partie, and Mr Kerr & he do very well, but alas! I dare not talk nonsense lest I lose all the little dignity I have among the sober sons of wisdom and discretion, and I have had not one hearty mouthful of laughter since that merry-melancholy moment we parted.’

The following day, Burns and companions were on their way again. After breakfasting at Hexham, they continued west.

Although Robert Burns only made a fleeting visit to Newcastle, his younger brother, William, did live and work here. He completed his apprenticeship at Messrs Walker and Robson, saddlers. He then briefly worked in London before his untimely death in 1790.

While William was trying to find work in Newcastle, Robert wrote to him: ‘I need not caution you against guilty amours – they are bad and ruinous everywhere, but in England they are the very devil’.

Commemorations

Robert Burns died in 1796 at the young age of 37, only nine years after his visit to Newcastle. By this time his work was extremely popular in Scotland and the tradition of Burns Night, in effect a second national day, began within a few years of his death. The first ‘Burns supper’ is said to have been held in Scotland in 1802 but it has been claimed that the first Burns club in the world was founded in Sunderland shortly afterwards. A Newcastle club was in existence by 1816.

Migration of Scots into north-east England grew during the nineteenth century and with it a strong attachment to the national poet of their homeland. Many events were held in January 1859 to commemorate the centenary of Burns’ birth, including a supper for 70 in Low Walker and a festival dinner for 400 in the Newcastle Town Hall. There were further events in 1896, the centenary of Burns’ death.

Walker

It was in this context that Walker Burns Club, which comprised mainly workers in the local shipyards, decided to donate to the people of their district a ‘monumental drinking fountain’. At the unveiling of the ‘Burns Memorial Fountain’ on 13 July 1901 the secretary of the club, John McKay, said that for four or five years (ie from around the time of the centenary of Burns’ death) the members had wanted to do something for the people who had supported them and so had saved the profits of the club’s programme of concerts and lectures. As he formally handed over the memorial to the chairman of Walker Urban District Council, he said the club members ‘were trying to do what they could to leave the world a better place than they found it and to more fully appreciate the beautiful and humane sentiments contained in nearly all Burns’ poems .’ He made no mention of Burns’ visit to Newcastle.

It was left to Hugh Crawford Smith, Liberal Unionist MP for Tyneside, who unveiled the fountain, to make passing reference to this visit:

‘[Burns] was once very near to Walker. In 1787, he came to Newcastle, slept there a night and then went home by way of Hexham and Carlisle. Burns never really got to Walker – laughter – but he might have done so if he could have foretold that more than a century later a drinking fountain would be erected to his honour’… the memorial would stand for all time as a practical manifestation of what the Burns club had done for Walker (Applause)’.

The event merited only four and a half lines in the ‘Evening Chronicle’:

‘A Burns memorial fountain, the gift of the Walker Burns Club was unveiled in Walker Park on Saturday by Mr H Crawford Smith MP, who together with Father Berry, chairman of the council, and other speakers, made some interesting remarks about the ploughman poet.’

However, luckily for us there was much more detail in Joseph Cowen’s more radical ‘Newcastle Daily Chronicle’ and other local papers in Northumberland, Durham and Scotland.

From them, we know that the memorial comprised an ornamental, iron drinking fountain topped by a bronze ‘statuette’ of the ‘National Bard’ which stood on a capital on top the fountain, which itself was mounted on a raised platform accessed by four steps and surrounded by flower beds. It must have been an impressive sight. Father Berry, leader of the council, was the first person to point out that the poet had his back to his homeland. This became a recurring theme over the years.

The drinking fountain was cast in Glasgow by Walter Macfarlane’s Saracen Foundry, the most important manufacturer of ornamental ironwork in Scotland. Among its surviving works in Britain are the Alexander Graham Memorial Drinking Fountain in Stromness and the Barton Arcade in Manchester. Overseas works included gates in India and Argentina, fountains in Tasmania, Malaysia and Cyprus and verandas in South Africa and Singapore (at the Raffles Hotel). The Walker Burns Club chose their fountain from a pattern book. It was designed in a way that a statue of choice could be added.

The statue, which depicted Burns with right arm outstretched in the act of reciting his song ‘A Man’s a man for A ‘That’, was sculpted by David Watson Stephenson of Edinburgh whose many well-known works include a bronze statue of William Wallace on the National Wallace Monument in Stirling and the figures of Mary Queen of Scots, Halbert Glendinning and James VI on the Sir Walter Scott Monument in Edinburgh. The Scots of Walker chose the very best craftsmen to make their memorial.

A shield attached to the capital between the fountain and the statue bore the inscription ‘Presented to the District Council by the Burns Cub, Walker on Tyne 1901’.

The capital also bore the final lines from Burns’ well-known song ‘A Man’s a Man for A ‘That’ :

‘It’s Coming Yet for A’ That

That Man To Man, the Warld O’er

Shall Brithers be for A’ That.’

The full song asserts that a man’s value lies not in his wealth, position or social class but in his mind and character. Of course, these sentiments still resonate today and the song is still performed in Scotland on major occasions, memorably at the opening of the Scottish Parliament and the funeral of Donald Dewar, the inaugural minister for Scotland. The Walker Burns Club’s choice of inscription has stood the test of time.

Fresh Water

So, it is very clear from accounts of the unveiling that the drinking fountain was considered at least as important a part of the gift as the statue.

Installation of free public drinking fountains, the first of which appeared in Liverpool in 1854, was often linked to the Temperance Movement, who wanted to give people a safe and easily available alternative to alcohol, although the irony of this in relation to Robert Burns was not lost at the unveiling. Expressing an expectation that the memorial would ‘stand for all time [dispensing] pure water’, Crawford Smith joked that Burns would probably have liked something stronger in it.

The Walker fountain had tin cups suspended on chains at the base to allow passers by to drink the water but even in 1901 the public health dangers of many people sharing unwashed vessels was recognised and safer designs were being introduced elsewhere. (But there were still similar cups at Armstrong Park’s ‘King John’s Well’, the postcard below also dating from 1901).

Interestingly, although they seemed to have had their day, there has been a revival of public drinking fountains in recent years in response to concerns about the use of plastic bottles, increasing summer temperatures and as an alternative to unhealthy sugary drinks. A 2019 campaign for the installation and restoration of drinking fountains in Newcastle seems to have stalled due to the current pandemic but the reasoning behind it is still strong.

Restoration

The first mention we have found of repairs to the monument was in 1956 when the council noted that the fountain was ‘now disused’. The plan was to point the masonry part of the base, remove the steps and clean and paint the statue. It would not be turned around to face Scotland!

Today painting a bronze statue sounds like an unusual piece of restoration work. Nevertheless, we know that the work was done and afterwards it was returned to Walker Park, where it stood until the mid 1970s at which time ‘vandals’ and ‘the passage of time’ had reportedly left it without a head and arms. In 1975, the North East Federation of Burns Societies, rather than the city council, commissioned another restoration by a Hatfield firm of welders where a Mr Bill Fraser, himself a Scot, led the work to pin the arms and head back onto the statue and recreate fingers missing from the the right hand with glass fibre.

This time, at least in the reports we have read, there was no mention at all of the fountain.

Heaton

The next newspaper report we have found dates from 24 February 1984. It was reported in ‘The Journal’ that the statue of Robert Burns had been ‘stolen from its home of five years in Heaton Park , and smashed to pieces by vandals’

Mr Max McGregor, president of the Ouseburn Burns Society, is reported as saying ‘The statue was donated to the city by a Burns society and was to have been used for our celebrations on Burns Night this January. This year’s visit had to be cancelled because of this affair’.

Mr Roger Neville, spokesman for Newcastle City Council, said: ‘The statue was stolen by youngsters and as they were rolling it away, it toppled down the hill and broke into pieces. It is now in our Jesmond Dene depot’.

So still no mention of the fountain and no photograph but, based on this report, we can apparently date the statue’s sojourn in Heaton Park from 1979 to 1984. There is at least one inaccuracy in the account though. As we know, the donation was to the Urban District of Walker, not the neighbouring City of Newcastle. And, as we’ll soon see, doubt has been cast on the date.

Forgotten

All went quiet for a decade when, in response to an enquiry from Newcastle United historian, Paul Joannou, ‘The Journal’ ran two articles which showed that collective memory can be very short. On 15 March, it asked ‘Was there ever a statue of Robert Burns on Tyneside?’

Joannou was enquiring as he was aware of a series of football matches in the 1920s, staged for the purpose of raising money for a statue to Burns in Newcastle. He said that large crowds watched legends such as Hughie Gallagher and Alex James and that players who took part were presented with a medal, one of which was on display in the Newcastle United museum. He had put an appeal in the club programme but nobody had come forward to say they knew of the statue.

At this stage ‘The Journal’ knew nothing about the statue either, with journalist Tony Jones writing ‘I reckon the nearest one to Newcastle is 90 miles away in Dumfries.’ However, the following day, it revealed to its readers that the statue had been found in storage ‘at a council depot’ (presumably Jesmond Dene where it had lain in pieces since 1984).

‘The Journal’ had ‘learnt ‘that the statue had been removed from Walker in 1979’, which fits in with the 1984 account in the same paper (so perhaps its own archive is where it learnt it from). Again, there was no mention of the fountain nor the 1975 restoration, only the temporary removal for repair in 1956. A photograph, showing the statue on a graffiti covered cylindrical column carrying a plaque, was labelled ‘Heaton Park, 1983’ but it is very difficult to see the surroundings.

The paper had by now been contacted by a reader who remembered walking past the memorial in Walker Park every day on his way to school in the 1950s but still no such memories had come to light of its much more recent time in Heaton Park. We are hoping that 26 years on, we will have more luck.

Football Fundraisers

‘The Journal’ was naturally bemused as to why fundraising football matches would be played to raise money for a statue particularly if there had been one all along. They wondered if the statue had originally stood somewhere else and only came to Walker after the 1920s.

We now know that the statue fund was for one in Newcastle, as opposed to Walker, and that the fundraising through popular and high profile football matches was extremely successful.

However, a spanner was thrown in the works by the Burns Federation, which at its annual conference in September 1926, passed a resolution to say that there should be no more statues and instead affiliated clubs should be encouraged to honour the poet’s memory by donating to local hospitals. An opinion piece in the ‘Dundee Telegraph’ didn’t mince words:

‘Few of the Burns statues are good, many are bad and a considerable number are very bad.’ Too generally they make the subject look like a moon-stricken idiot’.

We don’t know what the writer thought of the Walker statue but you can make up your own mind about its quality.

A number of contemporary portraits of Burns exist.

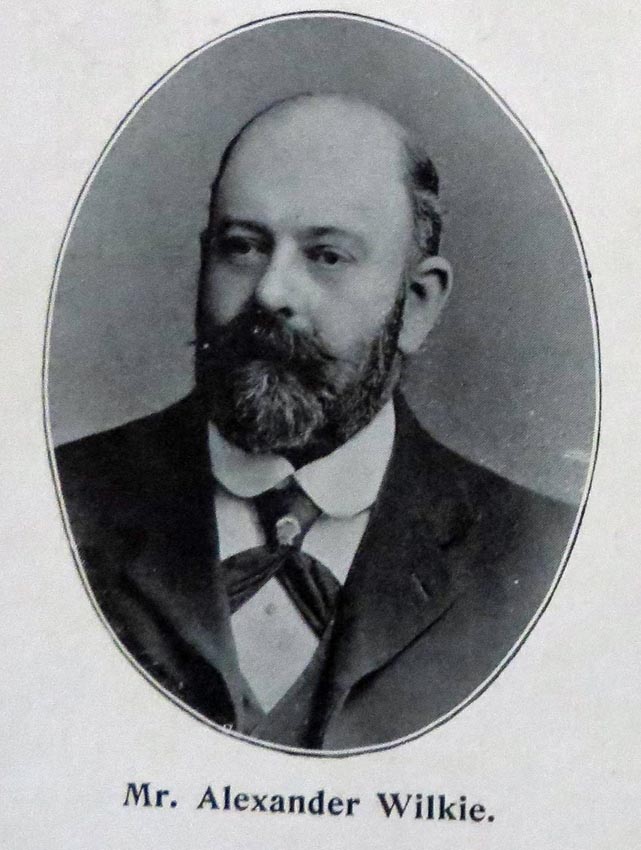

The honorary president of Newcastle Burns Club at this time was Sir Thomas Oliver who, though born in Ayrshire just like Robert Burns, was now a world famous professor of medicine at Durham University. He specialised in industrial diseases such as lead poisoning and had also been instrumental in raising the Tyneside Scottish Battalions during WW1. Former shipyard worker and trades unionist, Alexander Wilkie, once of Cardigan Terrace and Third Avenue and by this time of 36 Lesbury Road in Heaton, who had been Scotland’s first Labour MP, was an honorary vice president.

These were not men to mess with! In May 1927, in apparent defiance of the federation, the club reported that over £2,500 had already been raised and ‘with another £100 they could go ahead with the scheme and procure the site.’

Details thereafter are sketchy but the statue was never erected and we know that the Newcastle Burns Club donated considerable funds to local hospitals.

New Plaque

So by the second decade of the 21st century, all we had was one broken statue lying in pieces in Jesmond Dene council depot. The next document we have dates from around 2011 and confuses things further.

An entry in Tyne and Wear’s Historic Environment Record is headed ‘Robert Burns Memorial Fountain’ but states:

‘In 1901 a statue commemorating Rabbie Burns was erected in Walker Park by the local Burns Club supported by the numerous ship builders who moved to Walker from Clydesdale.The plaque reads ‘THIS STATUE WAS ERECTED IN WALKER PARK BY THE WALKER ON TYNE BURNS CLUB ON 13TH JULY 1901 TO MARK THE VISIT TO NEWCASTLE BY ROBERT BURNS ON THE 29TH MAY 1797. REMOVED TO THIS SITE BY THE CITY OF NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE ON THE 27TH SEPTEMBER 1975’. It is a bronze cast and is in very poor condition. It is presently stored at Jesmond Dene Nursery. The Walker Park lottery bid [2010] has plans to recast the statue and put it back into the park.’

So the fountain is mentioned in the heading but nowhere in the text and there is no mention of either of the original plaques but we find that a new plaque had been created at some point – it might well be the one in the 1983 photograph – and the date it gives for its removal to a new site is four years earlier that the dates we have seen so far. But does ‘this site’ even refer to Heaton Park or did it stand somewhere else after Walker but before Heaton? Confused? You bet! And that’s why we need you to wrack your brains and sift through your old photos.

Here, for the first time, we read the claim that the statue was erected to commemorate Burns’ visit to Newcastle and this might be a suitable point to question whether Burns really was a worthy recipient of such a memorial.

Slavery

It is 36 years since the Burns statue was ‘stolen by youngsters and as they were rolling it away, it toppled down the hill and broke into pieces’ but that sentence surely brought to mind recent scenes in Bristol and elsewhere. Thanks, in part, to the Black Lives Matter movement, we are much more aware of the flaws of historical figures once revered – by some.

Burns was honoured by the people of Walker and people like Heaton’s Alexander Wilkie because he was a poet who spoke for ordinary workers and their families. It may come as surprise then that the year before his visit to Newcastle, Burns had accepted a position as overseer at a friend’s sugar plantation in Jamaica, a plantation which was, of course, worked by slave labour.

In 1786, Burns faced financial ruin as his father’s death combined with the poor soil on the farm he worked with his brother had reduced both of them to near starvation. To compound matters, his love life was even more troubled than usual. It has been noted that Burns, ‘had been nearly married to his first love Jean (to the horror of her parents and the Church) but they had agreed to separate (without knowing that Jean was pregnant with twins); then Robert had fallen in love with another, ‘Highland Mary’ who died suddenly while waiting for him to come to her. Jean’s vindictive father sought court proceedings to arrest him so, like a fox with the hounds snapping at his heels, Robert needed to escape.’

He accepted Patrick Douglas’s offer of a post on a small team of overseers on his plantation. There are some who argue that this wasn’t such a bad decision as Burns was only to be a ‘bookkeeper’. But others have claimed that Burns would, ‘have a daily interface with the truth of slavery – from assisting in purchases, through recording punishments and deaths’. Burns himself described his role as ‘a poor Negro driver’, not a good look for a poet who revered as a champion of freedom and who came to Newcastle, shortly before 3,000 of its residents made their way to the Guildhall to sign a petition against the slave trade.

Fortunately both for Burns and his legions of fans down the centuries, in a last act of defiance before taking this huge step, he decided to publish his ‘Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect’. They were instantly acclaimed and so Burns was able to turn back from his journey west into the dark world of slavery administration and instead turn east to a brighter future in Edinburgh and fame and marriage to Jean. The next year he was able to do his literary tour and come south to Newcastle.

There is of course a great irony in the fact that Burns almost ended up playing a part in the deeply destructive and dehumanising slave trade and it is one that arguably cuts right to the heart of Scottish society today. Many of Burns’ poems spoke out strongly about freedom and against forms of human slavery. His national poem ‘Scots Wha Hae’, has its title taken from words attributed to Robert the Bruce before the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, where Bruce’s army won the national freedom of the Scots against a larger English army. But this is the rub; as has been pointed out on a recent BBC Scotland series, many Scots who are today advocating national freedom again, through a second independence referendum forget the major role Scotland played in the transatlantic slave trade. It was this trade that Burns himself nearly played a role in.

Burns’ only poem which is directly relevant to the issue of slavery is ‘The Slave’s Lament’ from 1792. This is clearly an abolitionist poem. It does beg the question then of just how was it that Burns so nearly became part of the trade he later seemed to abhor. There has been much speculation but we will never know.

But we do know that a young Abraham Lincoln came to the settlement of New Salem and craving books found a ready made library in the home of a Scottish neighbour Jack or Jock Kelso who, unsurprisingly given his name, was a Scotsman. It is said that Lincoln was heavily influenced by the poetry of Burns that Kelso had in his collection and this would help him on the road to becoming the US president who freed the slaves.

Another American who was to read Burns’ poems and be heavily influenced by themes of liberty and the brotherhood of men found among them, was escaped slave, Frederick Douglass. When Douglass visited Britain, he made a point of visiting Burns’ birthplace in Alloway. Like Burns, he visited Newcastle, and he became a freed slave due to the fund set up by two sisters-in-law from Jesmond. Douglass went on to become known as the ‘Father of the American Civil Rights Movement’ and a close adviser to President Lincoln. Perhaps we should leave the last words on the matter to Douglass. Speaking of Burns, he said ‘we may condemn his faults, but only as we condemn our own’ and he argued that Burns was ‘far more faultless than many who have come down to us on the pages of history as saints’, words which might serve as a warning to anyone planning to erect a statue to any historical figure in future.

Replica

Nevertheless in 2016, Burns’ statue was returned to Walker Park. A Heritage Lottery Fund grant was obtained for a revamp of the park as a whole and as part of that, a replica of the Burns statue was installed exactly where the original had stood – but this time facing Burns’ birthplace. At the same time, repairs were made to the original and it was placed in a new cafe in the park. There are now just three full length statues of Robert Burns in England, one in London’s Victoria Embankment Gardens – and two in Walker Park!

Talking in 2016, park ranger, Katharine Knox, noted that, ‘The statue was a prominent feature of the park and a lot of local people have memories of it’.

Newcastle City Council cabinet member for culture and communities, Kim McGuinness, added: ‘It’s really pleasing to see this statue, a prominent historical feature in the park, restored to its former glory and taking pride of place.’

It’s unfortunate that it was only the ‘statuette’ that was ‘restored to its former glory’. Somewhere along the line, the magnificent fountain, the quote from Burns and the plaque which explained who gave the statue to whom all became separated and, as far as we know, lost and there is nothing on the monument to tell passers by who the replica Walker Park statue depicts. There is brief information on information panels around the park which direct those interested into the cafe where the heavily restored original stand proudly along with detailed and well-presented information about Burns and the words of ‘A Man’s a man for A ‘That’, as well as a summary of the statue’s story.

At present, however, you can’t see the exhibition because, due to coronavirus, the cafe is offering a takeaway service only, alongside other community activities. Nevertheless, it’s easy to imagine that both Burns and Walker Burns Club would be satisfied at the current resting place of the the original statue, in a community hub, and they would understand why the display of a statue had to take second place to the incredible work YMCA staff and volunteers are doing to helping local people hit hard by the current pandemic.

Can You Help?

So, as you can see, there is much in the story of the Burns’ memorial which gives food for thought and much that has been forgotten or misremembered over the years. We would especially like to find out more about the statue’s stay in Heaton, which was well within living memory. Why Heaton? When was it here? Where did it stand? What became of the original fountain? Which way did Robbie face? Did you know who he was?

If you can help in any way, please get in touch. You can contact us either through this website, by clicking on the link immediately below the article title or by emailing chris.jackson@heatonhistorygroup.org

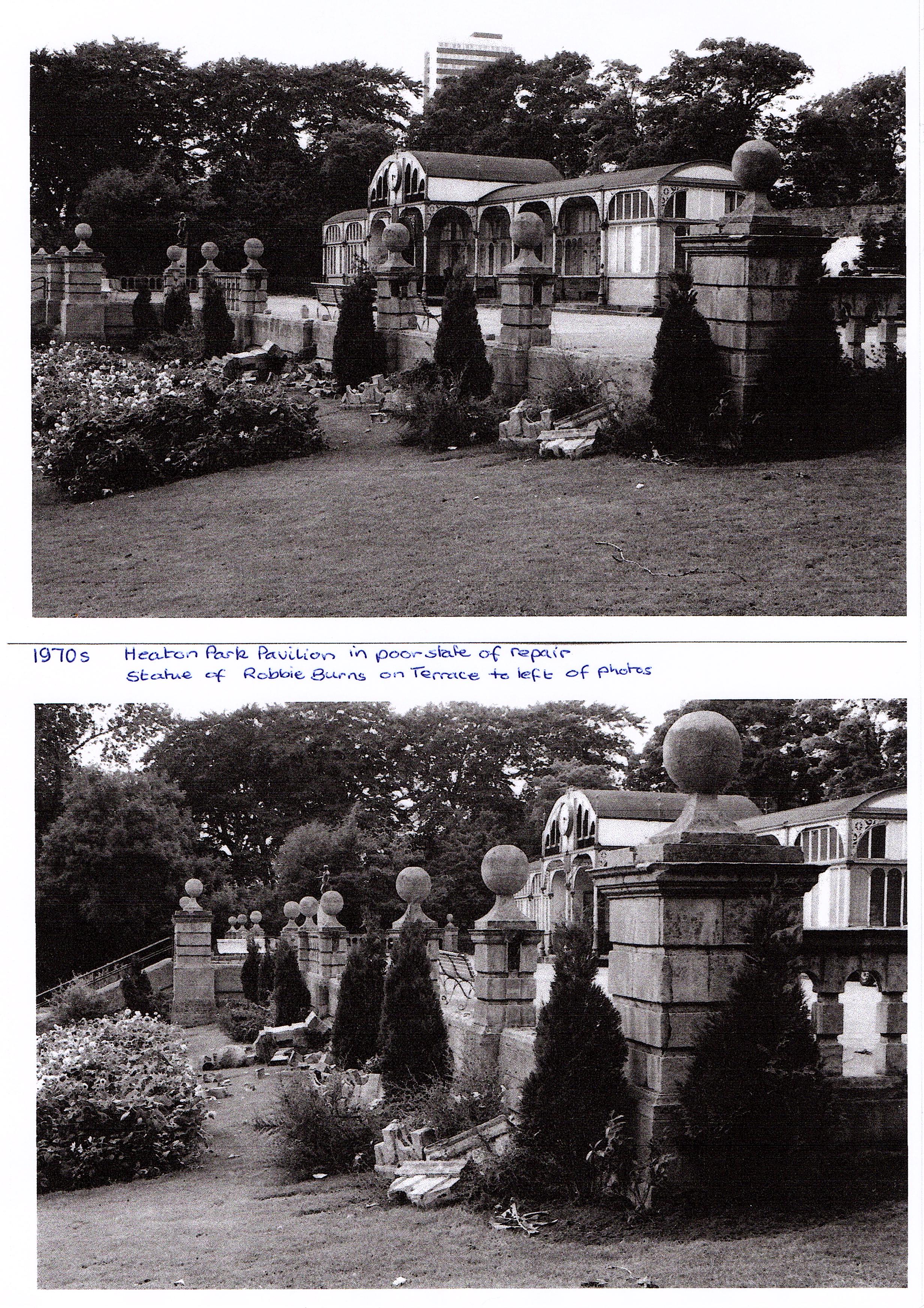

STOP PRESS

Before the ink was dry on our article, we had received the photographs below which, if you look carefully, show the statue in Heaton Park, on the far side of the pavilion before it was restored. It’s clear that the statue is mounted on a pedestal but there is no fountain. A big thanks to Ann Denton of Heaton History Group and Friends of Heaton Park. Do they stir any memories? Do you have a photo?

Acknowledgments

Researched and written by Peter Sagar of Heaton History Group, with additional material by Chris Jackson. Thank you also to Kevin Mochrie of Heaton History Group for sharing his library factsheet, to the staff and volunteers of YMCA Walker Park Cafe and Centre, who kindly gave us access to the cafe to photograph the Burns’ statue and to Ann Denton of Heaton History Group and Friends of Heaton and Armstrong Parks for supplying the photographs of the pavilion.

Sources

‘Burns: a biography of Robert Burns’ / James Mackay; Alloway Publlshing, 2004

‘Burns in the USA’, BBC Scotland

‘Myers’ Literary Guide: The North East’ / Alan Myers; 2nd Edition, 1997

‘Robert Burns: his connections to Newcastle and the North East’ / Kevin Mochrie. Newcastle City Library Factsheet, revised, January 2020.

‘Slavery: Scotland’s Hidden Shame’, BBC Scotland (TV programme)

burnswalkerstatue.wordpress.com

Robert Burns Memorial Drinking Fountain

https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/whats-on/arts-culture-news/burns-night-statue-newcastle-walker-15729980 11:54, 25 JAN 2019

https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/north-east-news/statue-great-rabbie-burns-returns-11778972

https://www.twsitelines.info/smr/13508

Shields Daily Gazette 15 July 1901

Evening Chronicle 15 July 1901 p2

Newcastle Daily Chronicle 15 July 1901 p 5

Journal and North Star 7 May 1927 p8

Journal 13 June 1956 p 5

Evening Chronicle 27 September 1963 p12

Journal 24 February 1984 p 5

Journal 15 March 1994 p

Journal 16 March 1994 p 17

Excellent article- I came across references to the statue when researching water supplies in Newcastle.

One small amendment is needed – It was Joseph Cowen with an e who was the newspaper owner/editor. His statue stands in front of Cross House at the junction of Westgate Rd and Fenkle St.

Hi Nichol, Thank you for spotting the typo. Will fix that.

I was actually looking for information about the domestic water supply in 1901 in places like Walker but couldn’t find anything much online. Please feel free to comment in that. Chris (HHG)

ON that!

A great article! The entry for the statue in the Lost Works chapter of Public Sculpture of North-East England (LUP, 2000) describes the Heaton Park pedestal as being approx 2m high and in stone. It refers to three more 1994 articles in the Journal on 18, 22 and 26 March – you might have seen those in addition to the ones you reference above, I guess containing much the same information. The entry says that in 1994 it was deemed too damaged to repair. What a fascinating story. Thanks.

Thanks for such a fascinating and diligently researched article. it just shows how “slippery” history can be, even recent history. On a minor point the Richardson sisters were Anna and Ellen who were sisters-in-law. They were Quakers, peace campaigners and anti-slavery activists who lived at 5, Summerhill Grove in Newcastle. A black plaque was unveiled here to Douglass and the Richardsons in March 2018. The price of Frederick Douglass’s freedom was £150 or $711 (£18,000 in 2020). £70 of this was raised in Newcastle and the remaining £80 in Edinburgh. This information was given in a lecture by Professor Leigh Fought at Newcastle University in June 2020.

A great article! The entry for the statue in the Lost Works chapter of Public Sculpture of North-East England (LUP, 2000) describes the Heaton Park pedestal as being approx 2m high and in stone. It refers to three more 1994 articles in the Journal on 18, 22 and 26 March – you might have seen those in addition to the ones you reference above, I guess containing much the same information. The entry says that in 1994 it was deemed too damaged to repair. What a fascinating story. Thanks.

Hi Jules, I hadn’t seen that ‘Public Sculptures’ entry. Thank you. Chris