Frederick Blenkinsop Robinson was born on 19 March 1900 and lived his entire life on Sixth Avenue, Heaton. He was the third of four children born to Joseph and Margaret Robinson. Joseph was a commercial traveller, born in York. He married Margaret Jane Blenkinsop of Newcastle in 1895 and the couple lived at no 13 Sixth Avenue. The 1911 census shows Joseph, aged 39 and Margaret, aged 41, living with their four children: Margaret May, aged 15; Joseph, aged 13; Frederick Blenkinsop, aged 11; and Thomas, aged 9. The family also had a lodger, William Blenkinsop, a 26 year old railway porter, who must have been a relative of Margaret.

Young life

Fred would have been only 14 at the start of the war and, like his siblings, was a pupil at Chillingham Road School. After leaving school, he became an apprentice fitter at Henry Watson and Sons Engineering Works in High Bridge, Walkergate. The company made cylinder blocks for commercial and marine engines as well as specialist pumps. An article in Commercial Motor on 5 September 1912, notes that the London General Omnibus Company were using cylinder blocks and pistons from Henry Watson and Sons exclusively for their B-type buses. The article particularly praises the quality of the work produced at the Walkergate factory in a new foundry specially built to produce commercial vehicle engines components.

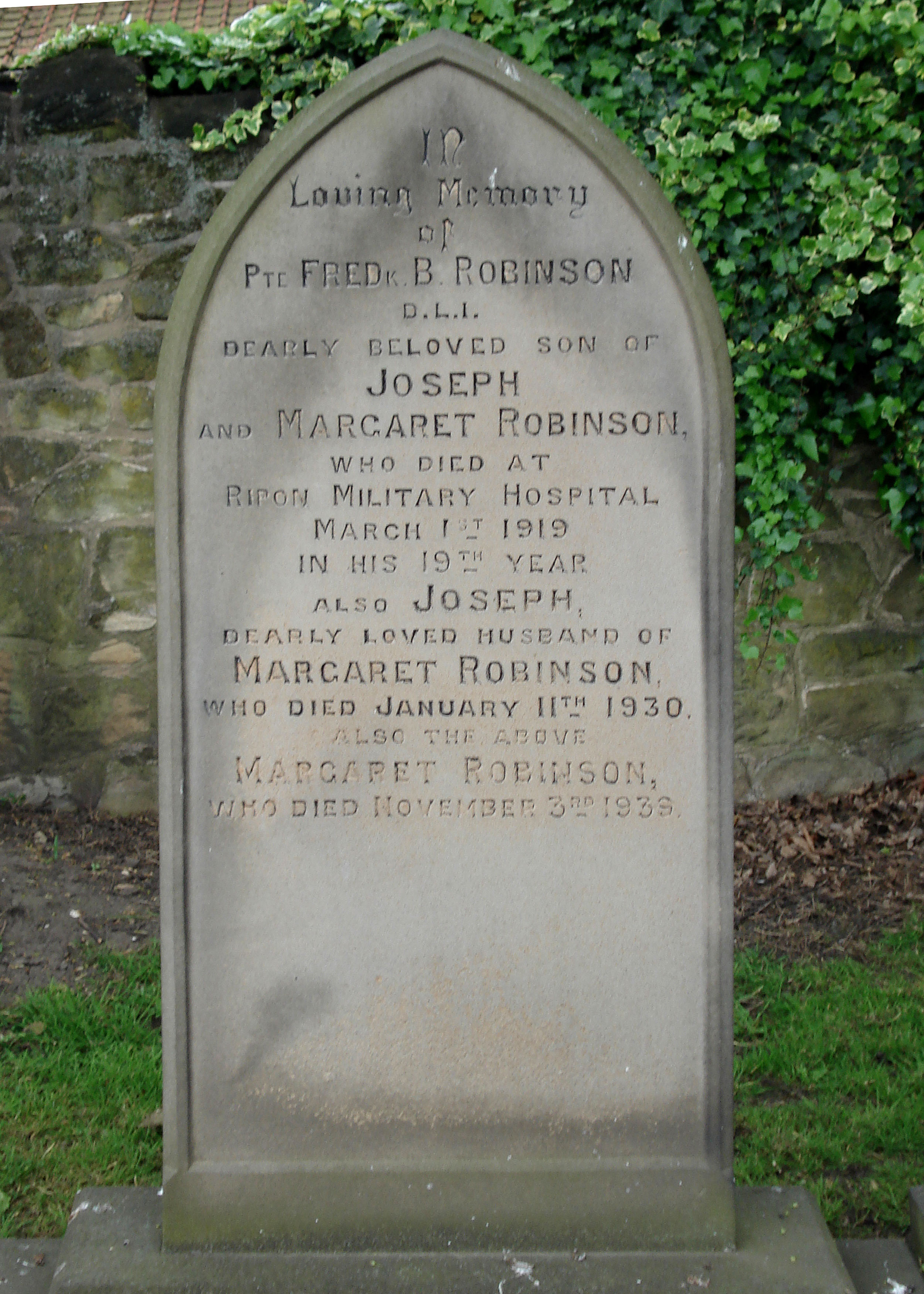

Fred was almost too young to have been involved in the war and certainly too young to have fought at the front (young men could join up at 18, but weren’t posted to the front until they reached 19). Yet he died on 1 March 1919, 18 days short of his 19th birthday, some four months after the end of the war and is listed as a casualty of war, buried in a Commonwealth War Grave at Byker and Heaton Cemetery.

His is a particularly sad story among many such stories from the war.

Military service

It is likely that Fred’s older brother, Joseph, had joined the forces when he was 18, two years before although no record of his military service survives. We know that he survived the war and is mentioned in a list of family in Fred’s military record. Fred was obviously keen to sign up to do his military service, as he attended his initial medical assessment on 26 March 1918, one week after his 18th birthday. He passed this and was enlisted on 19 April. On 19 August, 102540, Private Frederick Robinson of the 5th Reserve Battalion of The Durham Light Infantry was called up and posted to Sutton on Hull in East Yorkshire for his initial training.

Fred was in hospital – the St John’s VAD Hospital in Hull – when the armistice was signed, having fallen ill with diarrhoea on 10 October, which he took 35 days to recover from. He might reasonably have expected that his time in the army would either be short or would at least involve less risk of death or serious injury. In Fred’s case, his discharge was rather shorter than he might have expected. By December, a process of discharge on the grounds of disability had started. On 13 December in a personal statement, Fred records that he has chronic discharge from both ears and resultant deafness. This had started about a month before he had joined up, but had got worse since.

When he examined Fred on 30 January, Lieutenant JD Evans of the Royal Army Medical Corps recorded that ‘there is a high degree of deafness and discharge from both ears. He says that this is worse since joining the army and he has certainly become more deaf since joining the unit. He is utterly unable to hear any commands unless they are shouted close to his ears and he is quite unfit for camp life.’ He recommended discharge on the grounds that he was permanently unfit. Today, we would think little of an ear infection which would be quickly and effectively treated with a course of antibiotics, but in 1918 it could be a permanent disability, leaving lasting damage even if and when the infection cleared up.

On 2 February, Fred was transferred to the OC Discharge Centre at Ripon to prepare for discharge. Six days later, he was admitted to the Military hospital at Ripon with influenza. The medical record notes that he was admitted unconscious, before going on to develop bronchopneumonia and late emphysema. On 26 February, an attempt was made to relieve the emphysema surgically, but to no avail. Fred died on 1st March, with his family with next of kin with him.

Pandemic

The 1918 flu pandemic ran from January 1918 to December 1920 and was unusually deadly It infected 500 million people across the world, including remote Pacific islands and the Arctic, and killed 50 to 100 million of them: three to five per cent of the world’s population. Two factors made it particularly deadly. Firstly, the unique conditions of the war. While the location of the first cases is disputed, the crowded and unsanitary conditions at the front made an ideal breeding ground. What is more, cases of flu are often limited by having sufferers stay at home. During the war, the opposite happened, with those affected transferred away from the front to hospitals both locally and in the soldiers’ home country, spreading the disease around the world. Secondly, flu most often affects the weakest, killing the young and old and those with existing medical conditions. The 1918 pandemic killed mainly healthy adults. Modern research has concluded that the virus killed through a cytokine storm (overreaction of the body’s immune system). The strong immune reactions of young adults ravaged the body, whereas the weaker immune systems of children and middle-aged adults resulted in fewer deaths among those groups.

To maintain morale, wartime censors minimized early reports of illness and mortality in Germany, Britain, France, and the United States; but papers were free to report the epidemic’s effects in neutral Spain (such as the grave illness of King Alfonso XIII), creating a false impression of Spain as especially hard hit, thus the pandemic’s nickname Spanish flu.

Commemoration

In his report of Fred’s death, Major PW Hampton noted that ‘in my opinion death was attributable to service during the present war, viz exposure and infection on Home Service’. By doing so, he ensured that Fred could be buried in a Commonwealth War Grave and that his family would be entitled to a memorial scroll and plaque as well as service medals. This must have been of some comfort to his grieving family. Fred’s service record includes a copy of the slip that accompanied the memorial scroll to confirm receipt. This notes that the plaque will be issued directly from the Government plaque factory.

After the end of the war in 1918, Britain began the long process of commemorating the service of those who had lost their lives during its course. As part of this, the government issued to their next-of-kin (in addition to any of the standard campaign medals an individual might have been entitled to had they lived) what was known as the Memorial Plaque and the Memorial Scroll. The plaque was a bronze disc, about 5 inches in diameter, and depicted Britannia holding a trident whilst standing with a lion, holding an oak wreath above a rectangular tablet bearing the deceased’s name cast in raised letters. Rank and regiment was not included, since there was to be no distinction between sacrifices made by different individuals.

This was complimented by the Memorial Scroll, which provided additional information as to rank, branch of service or any decorations awarded.The scroll itself was a little smaller than a modern A4 sheet of paper, printed on thick card, and came in three main varieties. Those to the Army had a large blue H in the main text, with the rank/name/regiment hand-written at the bottom in red ink. Those to the Navy had a large red H, with the hand-written naming at the bottom in blue ink. Finally, those to the RAF had a large black H in the main text, with the hand-written naming at the bottom in both red and blue ink.

Clearly there was some delay in the issuing of plaques as a letter from Fred’s mother, Margaret, dated 13 November 1921 enquires about a memorial plaque and medals.

.

Fred was also commemorated on war memorials at Chillingham Road School and St Gabriel’s Church in Heaton.

Postscript

Fred wasn’t the only young person from the Avenues or from Heaton known to have died of flu (or as the result an unnamed disease thought likely to be influenza) during the 1918-19 pandemic. They include:

Able Seaman John James Hedley of 12 Eighth Avenue, husband of Corrie Hedley and formerly a boot salesman, who died on 16 October 1918 and is buried at Saint Andrew and Jesmond Cemetery.

This list will be updated as our ‘Heaton Avenues in Wartime’ research progresses.

Heaton Avenues in Wartime

This article was researched and written by Michael Proctor, with additional input by members of our ‘Heaton Avenues in Wartime’ research team. The project is supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund. If you have further information about anything relating to the article, please get in touch either via this website (by clicking on the link immediately below the article title) or by emailing: chris.jackson@heatonhistorygroup.org