On 20th June 2016 in Stratford upon Avon, amateur actors from The People’s Theatre, Heaton will appear in a production of ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ alongside professionals from the Royal Shakespeare Company. That performance, a reprise the following night and five nights at Northern Stage in March, will form part of the national commemoration of the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death and is a great honour for our local and much loved theatre company.

The People’s Theatre has links with the RSC going back many years. The Stratford company made Newcastle its third home back in the 1970s and the People’s has come to the rescue three times (1987, 1988 and 2004) when an extra venue was needed for one reason or another. But these are far from Heaton’s earliest connections with the ‘immortal bard’ and we’ve decided to explore some of them as part of our own contribution to ‘Shakespeare 400’.

The Name of the Roads

The most obvious references to Shakespeare in the locality are a group of streets in the extreme south and west of Heaton: Bolingbroke, Hotspur, Malcolm and Mowbray are all Shakespeare characters, as well as historical figures. And immediately north of them are Warwick Street and the Stratfords (Road, Grove, Grove Terrace, Grove West, Villas). But could the literary references be coincidental? Perhaps it was the real life, mainly northern, noblemen that were immortalised? Why would a housing estate, built from the early 1880s for Newcastle workers and their families, pay homage to a long-dead playwright. It’s fair to say our research team was surprised and delighted at what we found.

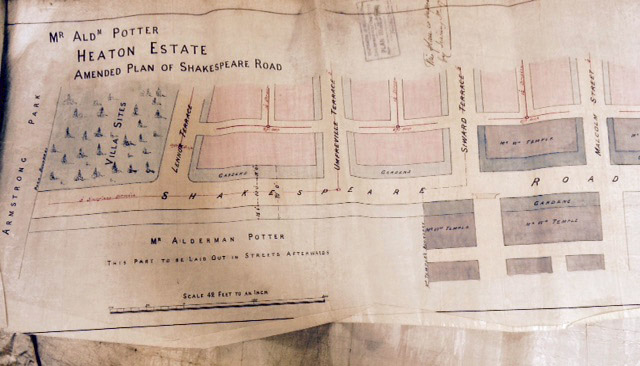

Two documents, one in Tyne and Wear Archives (V273) and one in the City Library, provided the key. Firstly, in the archives, we found a planning application from Alderman Addison Potter of Heaton Hall and his architect, F W Rich (who later designed St Gabriel’s Church). Their plans show Bolingbroke, Hotspur, Malcolm and Mowbray Streets, pretty much as they look now, but bordering them to the south is Shakespeare Road! No doubt now about the references. (Thank you to Tyne and Wear Archives for permission to use the images below.)

Not only that but Lennox, Siward, and Umfreville Terraces also appear. You’d be forgiven for not immediately getting the Shakespearian references there but Siward is the leader of the English army in Macbeth; Lennox, a Scottish nobleman in the same play and Umfreville, we’ve discovered, has a line which appears only in the first edition of Henry IV Part II but, like many of the others, the real person on which he was based has strong north east connections. Clearly the inspiration for the street names came from one or more people who knew their literature and their history.

But two sets of plans were rejected by the council for reasons that aren’t clear and, within a year, Addison Potter seems to have sold at least the leasehold of the land to a builder and local councillor called William Temple. Temple submitted new, if broadly similar, proposals. Building work soon started on the side streets but the previous year, Lord Armstrong had gifted Heaton Park to the people of Newcastle and the road to the new public space took its name. And nobody lives on Lennox, Siward or Umfreville Terraces either: they became Heaton Park View, Wandsworth Terrace and Cardigan Terrace.

But why Shakespeare? Whose idea was it? A newspaper article, dated 21 May 1898, in Newcastle City Library provided our next clue. A former councillor, James Birkett, was interviewed: ‘Mr Birkett himself occupied a cottage on the land which is now known as South View. There were another cottage or two near his, but they had nearly the whole of the district to themselves’. It continues ‘In front of them was the railway line, and behind was the farmhouse of a Mr Robinson. This house stood on the site now forming the corner of Heaton Park Road and Bolingbroke Street, and one of its occupants was Mr Stanley, who for many years was the lessee of the Tyne Theatre’.

The Tragedian

Further research showed that George William Stanley had a deep love not only of drama but of William Shakespeare in particular. He was born c 1824 in Marylebone, London. By 1851, Stanley described himself as a ‘tragedian‘ (ie an actor who specialised in tragic roles).

By 1860, he was in the north east. The first mention we have found of him dates from 28 July of that year, when he is reported to have obtained a licence to open a temporary theatre in East Street, Gateshead. A similar licence in South Shields soon followed. Later, we know that he opened theatres in Tynemouth and Blyth.

In 1861, he was staying in a ‘temperance hotel’ in Co Durham with his wife (Emily nee Bache) and four children: George S who is 8, Alfred W, 4, Emily F, 3, and Rose Edith Anderson, 1. He now called himself a ‘tragedian / theatre manager’. And he had turned his attention to Newcastle, where attempts to obtain theatre licences were anything but straightforward.

In June 1861, Stanley applied for a six month licence for theatrical performances in the Circus in Neville Street. He argued that one theatre (the Theatre Royal) in Newcastle to serve 109,000 people was inadequate; he promised that the type of performances (‘operatic and amphitheatre’) he would put on would not directly compete with existing provision; he produced testimonials and support from local rate payers; he gave guarantees that alcohol would not be served or prostitutes be on the premises. But all to no avail. The Theatre Royal strongly objected; an editorial in the ‘Newcastle Guardian’ supported the refusal. Appeal after appeal was unsuccessful. Stanley continued to use the wooden building as a concert hall and appealed against the decision almost monthly.

In October 1863, George Stanley made another impassioned speech, in which he begged to be allowed to practice his own art in his own building. He concluded: ‘I will not trouble your worships with any further remarks in support of my application, but trust that the year that witnesses the tercentenary of Shakespeare’s birth, will also witness the removal of any limitation against the performances of the plays of that greatest of Englishmen in Newcastle’. The Bench retired for thirty five minutes but finally returned with the same verdict as before.

Tercentenary

Despite his latest setback, George Stanley started 1864 determined to mark Shakespeare’s big anniversary. In the first week of January, he played Iago alongside another actor’s Othello in his own concert hall. ‘Both gentlemen have nightly been called before the curtain’.

The following week, a preliminary public meeting was held to hear a dramatic oration ‘On the Tercentenary of Shakespeare’ by G Linnaeus Banks of London, Honorary Secretary to the National Shakespeare Committee, and to appoint a local committee to arrange the celebrations in Newcastle. Joseph Cowen took the chair and George Stanley was, of course, on the platform. And it was he who moved the vote of thanks to Mr Banks for his eloquent address.

Unfortunately the festivities were somewhat muted and overshadowed by Garibaldi’s visit to England. (He had been expected to visit Newcastle that week, although in the event he left the country somewhat abruptly just beforehand). There was a half day holiday in Newcastle on Monday 25 April ‘but the day was raw and cold and the holiday was not so much enjoyed as it might otherwise have been’ and a celebration dinner in the Assembly Rooms, ‘attended by about 210 gentlemen’, was the main event. A toast ‘In Memory of Shakespeare’ was proposed, followed by one to ‘The Dramatic Profession’. George Stanley gave thanks on behalf of the acting profession.

Stanley continued to pay his own respects to the playwright. He engaged the ‘celebrated tragedian, Mr John Pritchard’ to perform some celebrated Shakespearian roles, with he himself playing Othello and Jago on alternate nights.

Tyne Theatre

In October 1865, Stanley’s wooden concert hall was damaged and narrowly escaped destruction in a huge fire that started in a neighbouring building. His determination to open a permanent theatre intensified and he had found powerful allies. On 19 January 1866, it was announced that an anonymous ‘party of capitalists’ had purchased land on ‘the Westgate’ for the erection of a ‘theatre on a very large scale’. They had gone to London to study the layout and facilities of theatres there. It was said that George Stanley would be the new manager.

In May of that year, in a sign that relations between Stanley and the Theatre Royal had at last thawed, Stanley performed there ‘for the first time in years’. And soon details of the new Tyne Theatre and Opera House began to emerge. Joseph Cowen, with whom Stanley had served on the Shakespeare Tercentenary Committee, was among the ‘capitalists’.

Cowen was a great supporter of the arts and an advocate for opportunities for ordinary working people to access them. He was incensed at the council’s continued blocking of Stanley’s various theatrical ventures and offered to fund the building of a theatre in which Stanley’s ‘stock‘ ( ie repertory) company could be based.

The opening been set for September 1867 but a licence was still required. Stanley applied again on 31 August. The hearing was held on Friday 13 September before a panel of magistrates which included Alderman Addison Potter of Heaton Hall – and this time Stanley and his influential backers were in luck. Just as well as it was due to open ten days later. And it did, with an inaugural address by George Stanley himself.

Despite his earlier claims that the Tyne Theatre wouldn’t compete with the Theatre Royal, Shakespeare was very much part of the programme in the early years: ‘As you Like It’, ‘The Merchant of Venice’, ‘King Lear’… But it was soon acknowledged that there was room for two theatres in Newcastle. Stanley soon found the time and the good will to play the role of Petruchio (‘The Taming of the Shrew’ ) at the Theatre Royal. He continued to manage the Tyne Theatre until 1881.

Heaton House

It was while still manager of the Tyne Theatre that Stanley moved to Heaton. His first wife had died in the early ’60s. He had remarried and with his second wife, Fanny, still had young children.

Heaton House, as we have heard, stood on what is now the corner of Heaton Park Road and Bolingbroke Street and the Stanley family were living there from about 1878.

The map below is from some years earlier (Sorry it’s such a low resolution. We will replace it with a better version asap) but gives a good impression of the rural character of Heaton at this time. In the top right hand corner of the map, is Heaton Hall, home of Alderman Addison Potter, one of Stanley’s few neighbours and the owner of the farmland on which Stanley’s house stood. Remember too that Potter had been a member of the panel that finally approved Stanley’s theatre in Newcastle.

Memorial

Potter and Stanley would surely have discussed matters of mutual interest. So while we might not know exactly how the naming of the streets on the east bank of the Ouseburn came about, we can surely assume that George William Stanley, actor, tragedian, Shakespearean, passionate promoter of theatre and neighbour of Potter at the time, played a part. It might have taken almost another twenty years and the name ‘Shakespeare Road’ didn’t make the final cut but Newcastle finally had the long-lasting tribute that George Stanley had wanted for the Shakespeare’s tercentenary.

By the early 1880s the area looked very different. William Temple had developed the fields to the south and west of Heaton Hall; Heaton House had been demolished and Bolingbroke Street and Heaton Park Road stood in its place; George Stanley had moved back to London.

Stanley would probably be surprised to know that his Tyne Theatre is about to celebrate its 150th anniversary; proud of the People’s Theatre‘s participation in the national commemorations a hundred and fifty two years after his own involvement and delighted that Shakespeare lives on in Heaton.

Can you help?

If you can provide further information about anything mentioned in this article please,contact us, either by clicking on the link immediately below the title of this article or by emailing chris.jackson@heatonhistorygroup.org

Shakespeare 400

This article was written by Chris Jackson and researched by Chris Jackson, Caroline Stringer and Ruth Sutherland, as part of Heaton History Group’s project to commemorate the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death.

We are interested in connections between Heaton and Shakespeare through its theatres, past and present; writers, actors – and of course, the famous brick Shakespeare on South View West.

We are also researching and writing about some of the people who have lived in the ‘Shakespeare Streets’: initially, we are looking at Bolingbroke, Hotspur, Malcolm, Mowbray and Warwick Streets plus Stratford Grove, Stratford Grove Terrace, Stratford Grove West, Stratford Road, and Stratford Villas.

If you would like to join our small friendly research group or have information, photos or memories to share, please contact us, either by clicking on the link immediately below the title of this article or by emailing chris.jackson@heatonhistorygroup.org

This must be the same William Temple of Temple’s Folly fame I think.

Yes, I’m sure it will be the same man who built the building which later became the Heaton Electric Cinema and then the bingo hall. It seems that it was never occupied as a house as intended partly because it was the subject of litigation which dragged on for many years.

Ginny Mason, George Stanley’s great great granddaughter, has written to us from York:

Have read “A road by any other name” and found it so interesting.

It seems quite likely that Stanley influenced the eventual street names during his years at Heaton with his theatrical connections and love of Shakespeare. Amazing how these things come to light.

George Stanley’s daughter, by Emily Bache, was Rose Edith Anderson Stanley, born at Berwick in 1860. She married my great grandfather, William Boocock, a builder, who became Clerk of Works to Newcastle City Council. He was involved in the building of the RVI, Armstrong College, Cross House and the Newcastle City Hall and Baths. On their marriage certificate in 1883, George Stanley signs his name as father and his “Rank or Profession” as Gentleman!

Many of George’s children went into theatre. He had four children with Emily and a further four daughters with Francis. Spreading far and wide, America, Australia, his family’s theatrical heritage lived on.

Have you visited the Theatre recently as there are some wonderful new panels of the theatre’s history on the Ground floor. It is open each day, I believe. I have received much information from them regarding Stanley’s great contribution as an actor and lessee/ manager. There seems to be only the one “portrait”, which we all have, it would be great if other pictorial stuff came to light. It is an on-going search!!

I think your contribution to “Shakespeare 400” is very exciting and I hope you will keep me in “the loop”

We’ve been wondering whether we have actually identified all the streets with a Shakespeare connection. For example, who was Molyneux Street named after? How about Emery Molyneux, the first English maker of globes. This extract is from Wikipedia:

‘The appearance of Molyneux’s globes had a significant influence on the culture of his time. In Shakespeare’s The Comedy of Errors, written between 1592 and 1594, one of the protagonists, Dromio of Syracuse, compares a kitchen maid to a terrestrial globe: “No longer from head to foot than from hip to hip: she is spherical, like a globe; I could find out countries in her.”[64] The jest gained its point from the publication of the globes; Shakespeare may even have seen them himself.[36] Elizabethan dramatist Thomas Dekker wrote in one of his plays published in The Gull’s Horn-book (1609):[7]

What an excellent workman, therefore, were he that could cast the globe of it into a new mould. And not to make it look like Molyneux his globe, with a round face sleeked and washed over with white of eggs, but have it in plano as it was at first, with all the ancient circles, lines, parallels and figures.[65]

It has been suggested that the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, the playing company that Shakespeare worked for as an actor and playwright for most of his career, named their playing space the Globe Theatre, built in 1599, as a response to the growing enthusiasm for terrestrial and celestial globes stimulated by those of Molyneux.[66]

In Twelfth Night (1600–1601),[67] Shakespeare alluded to the Wright–Molyneux Map when Maria says of Malvolio: “He does smile his face into more lynes, than is in the new Mappe, with the augmentation of the Indies.”[59]’

You can read the full Wikipedia entry for Emery Molyneux here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emery_Molyneux

Pure speculation but could be?

Dr Adam Hansen, Senior Lecturer in Englsh at Northumbria University, is organising a conference on Shakespeare in the north at the Lit and Phil on June 2 and has been in touch by email. He said: ‘As a Shakespearean scholar, as a former resident of Warwick Street, and as someone who has wondered at the provenance of those street names for several years myself (even going to the extent of contacting the council about them for information, to no avail), I was fascinated…’

He’s even invited us to present at the conference: http://www.northumbria.ac.uk/shakespeareinthenorth

We have received an email from

Jonathan Pritchard-Barrett, the great great grandson of John Pritchard, the tragedian mentioned in the article, giving more details about his ancestor’s life. We didn’t know that he died on 24 December 1868, after being taken ill while on stage at Dundee. He was brought back to Newcastle but died shortly afterwards, aged only 38.He was buried in St Andrew’s Cemetery.

Two weeks after his death, Pritchard’s widow gave birth to his son at Rye Hill Street.

Some two years later a memorial, designed and executed by Mr George Burn, sculptor, Neville Arcade, was erected over his grave.